1910 Giro d'Italia

2nd edition: May 18 - June 5

Results, stages with running GC, photos and history

1909 Giro | 1911 Giro | Giro d'Italia Database | 1910 Giro Quick Facts | 1910 Giro d'Italia Complete Final GC | Teams | Stage results with running GC | The Story of the 1910 Giro d'Italia

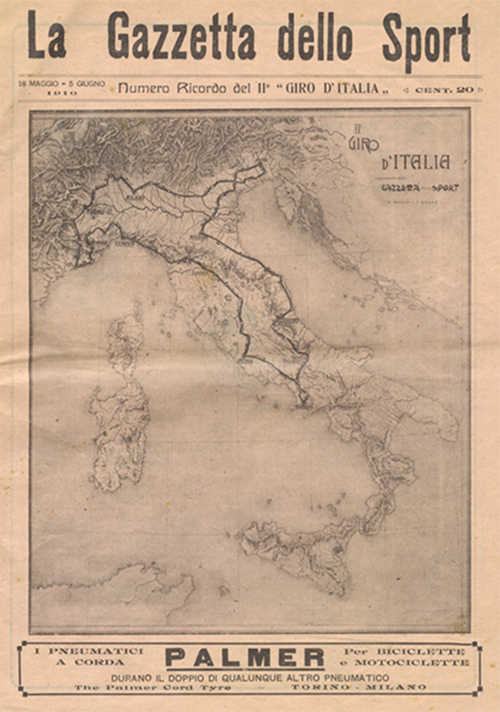

Map of the 1910 Giro d'Italia.

Les Woodland's book Paris-Roubaix: The Inside Story - All the bumps of cycling's cobbled classic is available in print, Kindle eBook & audiobook versions. To get your copy, just click on the Amazon link on the right.

2890 km raced at an average speed of 26.11 km/hr.

101 starters and 20 classified finishers.

Like the 1909 Giro and through the 1913 edition, the 1910 Giro d'Italia General Classification was based on points.

The unofficial times for the top riders:

- Carlo Galetti: 114hr 24min

- Eberardo Pavesi @ 1hr 20min

- Luigi Ganna @ 2hr

- Ezio Corlaita @ 2hr 52min

- Emilio Chironi @ 5hr 44min

1910 Giro d'Italia Complete Final General Classification:

Carlo Galetti (Atala-Continental): 28 points

Carlo Galetti (Atala-Continental): 28 points- Eberardo Pavesi (Atala-Continental): 46

- Luigi Ganna (Atala-Continental): 51

- Ezio Corlaita (Independent): 71

- Emilio Chironi (Otav-Pirelli): 77

- Battista Danesi (Atala-Continental) : 87

- Clemente Canepari (Otav-Pirelli): 102

- Giovanni Marchese (Otav-Pirelli): 114

- Ildebrando Gamberini: 120

- Giuseppi Galbai: 132

- Augusto Rho: 137

- Antonio Rontondi: 139

- Giuseppe Perna: ?

- Cesare Osnaghi: 145

- Amedeo Dusio: 149

- Alberto Sonetti: 151

- Mario Secchi: 156

- Giovanni Scarpetta (tied for 17th): 156

- Luigi Rotta (tied for 17th): 156

- Umberto Turconi: 161

Highest placed independent rider: Ezio Corlaita

Winning team: Atala

1910 Giro stage results with running GC:

Stage 1: Wednesday, May 18, Milano - Udine, 388 km

101 starters, 85 finishers.

- Ernesto Azzini: 13hr 16min (29.35 km/hr)

- Carlo Galetti

- Constant Ménager

- Lauro Bordin

- Ezio Corlaita

- Battista Danesi

- Lucien Petit-Breton

- Eberardo Pavesi

- Vincenzo Borgarello

- Mario Pesce

GC after Stage 1:

- Ernesto Azzini: 1 point

- Carlo Galetti: 2

- Constant Ménager: 3

- Lauro Bordin: 4

- Ezio Corlaita: 5

- Battista Danesi: 6

- Lucien Petit-Breton: 7

- Eberardo Pavesi: 8

- Vincenzo Borgarello: 9

- Mario Pesce

Stage 2: Friday, May 20, Udine - Bologna, 322.4 km

85 starters, 75 finishers

- Jean-Baptiste Dortignacq: 10hr 31min 38sec. 30.66 km/hr

- Carlo Galetti

- Lucien Petit-Breton

- Constant Ménager

- Luigi Azzini

- Luigi Ganna

- Pierino Albini

- Maurice Brocco

- Battista Danesi

- Giuseppe Contesini

GC after Stage 2:

- Carlo Galetti: 4 points

- Constant Ménager: 8

- Lucien Petit-Breton: 11

- Ernesto Azzini: 12

- Battista Danesi: 15

- Pierino Albini: 19

- Ezio Corlaita: 19

- Luigi Azzini: 21

- Eberardo Pavesi: 21

- Jean-Baptiste Dortignacq: 22

Stage 3: Sunday, May 22, Bologna - Teramo, 345.2 km

65 starters, 47 finishers

- Carlo Galetti: 10hr 54min 31.67 km/hr

- Luigi Ganna

- Eberardo Pavesi

- Lucien Petit-Breton

- Pierino Albini

- Emilio Chironi

- Enrico Sala

- Ezio Corlaita

- Constant Ménager

- Jean-Baptiste Dortignacq

GC after Stage 3:

- Carlo Galetti: 5 points

- Lucien Petit-Breton: 15

- Constant Ménager: 17

- Pierino Albini: 22

- Ernesto Azzini: 24

- Eberardo Pavesi: 24

- Ezio Corlaita: 27

- Luigi Ganna: 28

- Battista Danesi: 28

- Jean-Baptiste Dortignacq: 32

Stage 4: Tuesday, May 24, Teramo - Napoli, 319.5 km

47 starters, 23 finishers

![]() Ascents: Croce, Roccaraso, Rionero Sannitico, Macerone

Ascents: Croce, Roccaraso, Rionero Sannitico, Macerone

- Pierino Albini: 14hr 5min 10sec. 22.7 km/hr

- Maurice Brocco

- Jean-Baptiste Dortignacq

- Carlo Galetti

- Eberardo Pavesi

- Ezio Corlaita

- Clemente Canepari

- Emilio Chironi

- Giuseppe Perna

- Ildebrando Gamberini

GC after Stage 4:

- Carlo Galetti: 10 points. judges assessed Galetti a 1-point penalty

- Pierino Albini: 23 (abandoned)

- Eberardo Pavesi: 30. reflects 1-point penalty

- Ezio Corlaita: 33

- Jean-Baptiste Dortignacq: 35 (abandoned)

- Emilio Chironi: 39

- Battista Danesi: 42

- Luigi Ganna: 47

- Clemente Canepari: 60

- Mario Bruschera: 68

Stage 5: Thursday, May 26, Napoli - Roma, 192.3 km

23 starters, 22 finishers

- Eberardo Pavesi: 6hr 41min. 28.77 km/hr

- Luigi Ganna

- Ezio Corlaita

- Carlo Galetti

- Mario Bruschera

- Battista Danesi

- Giovanni Marchese

- Cesare Osnaghi

- Emilio Chironi

- Clemente Canepari

GC after Stage 5:

- Carlo Galetti: 14 points

- Eberardo Pavesi: 31

- Ezio Corlaita: 36

- Battista Danesi: 48

- Emilio Chironi: 48

- Luigi Ganna: 49

- Clemente Canepari: 70

- Mario Bruschera: 73

- Giuseppe Perna: 75

- Ildebrando Gamberini: 82

- Giovanni Marchese (tied for 10th): 82

Stage 6: Saturday, May 28, Roma - Firenze, 327.5 km

25 starters, 25 finishers

![]() Ascent: Perugia

Ascent: Perugia

- Luigi Ganna: 11hr 39min. 28.2 km/hr

- Carlo Galetti

- Emilio Chironi

- Clemente Canepari

- Ezio Corlaita

- Eberardo Pavesi

- Alfredo Sivocci

- Battista Danesi

- Mario Bruschera

- Giovanni Marchese

GC after Stage 6:

- Carlo Galetti: 16 points

- Eberardo Pavesi: 37

- Ezio Corlaita: 39

- Luigi Ganna: 43

- Emilio Chironi: 52

- Battista Danesi: 56

- Clemente Canepari: 74

- Mario Bruschera: 78

- Giovanni Marchese: 81

- Alfredo Sivocci: 84

Stage 7: Monday, May 30, Firenze - Genova, 263.5 km

25 finishers

![]() Ascent: Braceo

Ascent: Braceo

- Luigi Ganna: 10hr 28min 15sec. 25.37 km/hr

- Carlo Galetti

- Clemente Canepari

- Eberardo Pavesi

- Battista Danesi

- Ildebrando Gamberini

- Alfredo Sivocci

- Giovanni Marchese

- Emilio Chironi

- Mario Bruschera

GC after Stage 7:

- Carlo Galetti: 18 points

- Eberardo Pavesi: 41

- Luigi Ganna: 45

- Ezio Corlaita: 57

- Emilio Chironi: 60

- Battista Danesi (tied for 5th): 60

- Clemente Canepari: 77

- Mario Bruschera: 88

- Giovanni Marchese: 90

- Alfredo Sivocci: 92

Stage 8: Wednesday, June 1, Genova - Mondovì, 206 km

28 starters, 28 finishers

![]() Ascent: Giovi

Ascent: Giovi

- Carlo Galetti: 8hr 35min 21sec

- Eberardo Pavesi

- Luigi Ganna

- Emilio Chironi

- Ildebrando Gamberini

- Clemente Canepari

- Ezio Corlaita

- Giovanni Marchese

- Battista Danesi

- Mario Bruschera

GC after Stage 8:

- Carlo Galetti: 19 points

- Eberardo Pavesi: 43

- Luigi Ganna: 48

- Emilio Chironi: 64

- Ezio Corlaita: 65

- Battista Danesi: 69

- Clemente Canepari: 83

- Mario Bruschera: 98

- Giovanni Marchese (tied for 8th): 98

- Alfredo Sivocci: 105

- Ildebrando Gamberini: 108

Stage 9: Friday, June 3, Mondovì - Ventimiglia - Torino, 333 km

28 starters, 26 finishers

![]() Ascents: Nava, San Bartolomeo, Tenda

Ascents: Nava, San Bartolomeo, Tenda

- Eberardo Paversi: 12hr 49min. 26.0 km/hr

- Luigi Ganna

- Ezio Corlaita

- Carlo Galetti

- Giovanni Marchese

- Emilio Chironi

- Alfredo Sivocci

- Ildebrando Gamberini

- Mario Bruschera

- Battista Danesi

GC after Stage 9:

- Carlo Galetti: 23 points

- Eberardo Pavesi: 44

- Luigi Ganna: 50

- Ezio Corlaita: 68

- Emilio Chironi: 70

- Battista Danesi: 79

- Clemente Canepari: 96

- Giovanni Marchese: 103

- Mario Bruschera: 107

- Alfredo Sivocci: 112

10th and Final Stage: Sunday, June 5, Torino - Arona - Milano, 277.5 km

![]() Ascent: Serra

Ascent: Serra

- Luigi Ganna: 11hr 20min 20sec. 24.48 km/hr

- Eberardo Pavesi

- Ezio Corlaita

- Ildebrando Gamberini

- Carlo Galetti

- Clemente Canepari

- Emilio Chironi

- Battista Danesi

- Augusto Rho

- Giuseppe Galbai

1910 Complete Final General Classification

Atala Continental

Atena-Dunlop

Bianchi-Dunlop

Legnano-Dunlop

Otav-Pirelli

Stucchi-Pirelli

The Story of the 1910 Giro d'Italia

This excerpt is from Bill and Carol McGann's book The Story of the Giro d'Italia, A Year-by-Year History of the Tour of Italy, Vol 1: 1909 - 1970 is available in print, Kindle eBook & audiobook versions. To get your copy, just click on the Amazon link on the right.

1910. Like the first Tour de France, the first Giro was a wild success. For the second edition the ambitious organizers expanded their event from eight to ten stages and increased the overall length by more than 500 kilometers to 2,987. The average stage length at 299 kilometers was only slightly shorter than 1909’s, though the first stage—from Milan to Udine in the far northeastern corner of Italy—was still a cruel 388 kilometers long.

A change was made to the scoring. As usual, the stage winner would earn one point, second place two points, up to the fiftieth-place finisher who would get fifty. All riders coming in fifty-first and after would now get fifty-one points. Given the chaos of some of the finishes, this was a prudent and fair change. Highlighting the importance of the Giro to La Gazzetta’s fortunes, Emilio Colombo began personally following the race, turning in a report after each stage. In 1909 La Gazzetta’s owners had hired Colombo to become their editor. He remained in that position until 1936, when he would resign in a bitter row with writer Bruno Roghi, who then became the paper’s editor.

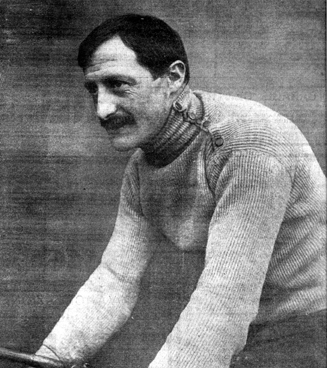

Painful would be the word to describe how Galetti found his narrow loss the previous year. He methodically prepared for the new edition and when the Giro started in Milan on May 18, he was in superb condition. Galetti was from the Milan suburb of Corsico. Because of his Milanese origins and his light, quick nimble way of riding he was given the nickname il Scoiattolo dei Navigli, meaning the “squirrel of the canals”, referring to the canals that criss-crossed Milan. Like today’s Italian sportswriters, those of the era loved to give athletes nicknames, personalizing the competitors and making them important and understandable to the reader.

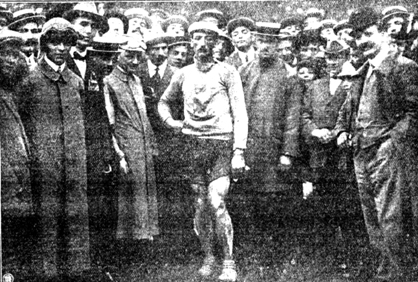

An undated photo of Carlo Galetti

Among the 101 riders who lined up to start the 1910 Giro was Petit-Breton, ready to give it another try. He was joined by another superb Tour rider, Jean-Baptiste Dortignacq, second in the 1904 Tour, third in 1905 and winner of several Tour stages. The peloton included the cream of Italian racing, among them Ganna, Rossignoli, Eberardo Pavesi and Ezio Corlaita. The 1910 Giro peloton also had its first Germans, Arno Ritter and Karl Dittenbrandt, neither of whom finished.

Galetti was second to Ernesto Azzini at the first stage’s finish in Udine, but for Ganna the stage was a disaster. With the points system, his 21st place after getting a flat tire put the Giro out of reach the first day.

Dortignacq broke away with Galetti to win the second stage into Bologna while Petit-Breton was third. Not only was this the first Giro stage won by a foreigner, but the General Classification podium now had two Frenchmen. Galetti was the leader with another Frenchman, Constant Ménager, sitting in second place and Petit-Breton third.

This French success generated an immediate reaction by the Italians. The foreign racers were attacked by the disappointed and angry tifosi at the finish in Bologna. Within the peloton, the Italians riders decided to unite against their French rivals.

The three best Italian riders, Galetti, Ganna and Pavesi, all riding for Atala, were able to escape and roll across the line in that order in Teramo at the end of the third stage. Petit-Breton, the first of the rest, came in 22 minutes later. Galetti’s grip on the lead was firm. After three stages he had only five points while Petit-Breton was second with fifteen. Dortignacq was ninth with 32 points. The Atala riders, dubbed the “Three Musketeers” by the press, had, with the help of their compatriots, made life dreadfully hard for the French.

Galetti leads at the start of a stage.

Two days later, stage four took the riders from Teramo, near the Adriatic coast, over the Apennines to Naples. At this point the peloton was down to just 47 riders, which did not include Petit-Breton, who abandoned. Pierino Albini won the stage with Frenchmen Maurice Brocco and Dortignacq right behind him.

Before the start of the fifth stage, Dortignacq became ill and abandoned. He was so sick that the police, suspecting foul play, launched an investigation. I have some English-language accounts of Dortignacq’s trouble, all probably originating from the same source, that say that as a result of this investigation twenty riders were disqualified, but I can find no mention of this mass punishment in Italian-language accounts of the 1910 Giro. All sources agree there were 47 starters at the beginning of stage four and only 23 classified finishers. I believe that the attrition was a result of the extreme difficulty of the 319-kilometer trans-Apennine stage rather than police action.

After stage five, the General Classification stood thus:

1. Carlo Galetti: 14 points

2. Eberardo Pavesi: 31

3. Ezio Corlaita: 36

4. Battista Danesi: 48

Although the Three Musketeers had, along with the other Italian riders, united against foreign riders, they fought each other tooth and nail. In fact, from the fifth stage, which Pavesi won, the race was the Musketeers’ personal property. Ganna took the sixth and seventh stages, Galetti the eighth and Pavesi the ninth. At this point Galetti had a 21-point lead over Pavesi. Only a catastrophe could prevent his winning this second Giro.

That catastrophe almost happened in the final leg, from Turin to Milan. Partway though the stage Galetti crashed into a hay wagon. Ganna won the stage while a torn and bloody Galetti still managed to finish fifth. Galetti had won the second running of the Giro d’Italia by a commanding margin. The 1910 Giro was hard-fought: of the 101 starters who left Milan, only 21 made it back. Typical of the times, there are contradictory numbers from La Gazzetta for the official classification and there may have been only 20 official finishers.

Final 1910 Giro d’Italia General Classification:

1. Carlo Galetti (Atala-Continental): 28 points

2. Eberardo Pavesi (Atala-Continental): 46

3. Luigi Ganna (Atala-Continental): 51

4. Ezio Corlaita (independent): 71

5. Emilio Chironi (Otav-Pirelli): 77

Galetti in Milan

There were several great Italian champions who made their mark on the Giro but could get no traction in the Tour de France, just as several Tour victors had nothing to show for their Giro attempts. The races are profoundly different. Galetti was probably the first of the good Italian racers who found no success in France. He entered the Tour three times (1907, ’08, and ’09) and abandoned each time, yet the rest of his career was stunning.

The timing of the two great races has an enormous effect on their outcomes. Whenever I ask professional riders about the difference between the Tour and the Giro they always cite the weather. The Tour’s July running brings summer’s baking heat, making it an ordeal for riders who can’t take it. The Giro’s spring timing means severe and unpredictable weather can determine the race’s outcome, especially in the high mountains.

The period before the First World War is often referred to by cycling historians as the heroic or pioneer era and Galetti is considered by many to be the finest of the Italian pioneer racers. He had been a typographer working in Milan in 1901 when one of the cycling Azzini brothers (Ernesto Azzini won the first stage of the 1910 Giro) gave Galetti a bike. His natural talent soon proved itself. He achieved high placings in 1902 and by 1904 was winning races alongside teammates Ganna and Pavesi. He was described by journalists of the time as a calculating rider, even cunning, always aware of his surroundings.

Galetti was also a generous competitor, well liked though he did have a terrible falling out with Gerbi in 1912. By then Gerbi had his own bicycle factory but Galetti chose instead to ride for Atala. Galetti proposed a wager (thought up by Pavesi) to settle things between the two, an individual time trial over the 300-kilometer Tour of Lombardy route. It took over 25 hours in miserable weather to complete the hilly route with Galetti beating Gerbi by almost five minutes.

.