1961 Giro d'Italia

44th edition: May 20 - June 11

Results, stages with running GC, photos and history

1960 Giro | 1962 Giro | Giro d'Italia Database | 1961 Giro Quick Facts | 1961 Giro d'Italia Final GC | Stage results with running GC | The Story of the 1961 Giro d'Italia

Les Woodland's book Tour de France: The Inside Story - Making the World's Greatest Bicycle Race is available in print, Kindle eBook and audiobook versions. To get your copy, just click on the Amazon link on the right.

4,004 km raced at an average speed of 35.934 km/hr

170 starters and 92 classified finishers.

Jacques Anquetil failed in his attempt to do the Giro/Tour double. He took the lead in the stage nine time trial, but inattention on Anquetil's part in stage 14 allowed Arnaldo Pambianco to escape and take the lead.

Anquetil was never able to make good that initial loss, and in fact lost still more time to Pambianco over the succeeding stages.

This was Pambianco's sole Giro championship. He never even made the podium again.

Anquetil went on to ride a fantastic Tour de France taking the lead on the first day and holding it for the rest of the race.

1961 Giro d'Italia Final General Classification:

Arnaldo Pambianco (Fides) 111hr 25min 28sec

Arnaldo Pambianco (Fides) 111hr 25min 28sec- Jacques Anquetil (Fynsec-Helyett) @ 3min 45sec

- Antonio Suárez (Ferrys) @ 4min 17sec

- Charly Gaul (Gazzola) @ 4min 22sec

- Guido Carlesi (Philco) @ 8min 8sec

- Hans Junkermann (Gazzola) @ 12min 25sec

- Rik van Looy (Faema) @ 12min 38sec

- Guillaume van Tongerloo (Faema) @ 14min 18sec

- Carlo Brugnami (Torpado) @ 16min 5sec

- Nino Defilippis (Carpano) @ 16min 23sec

- Imerio Massignan (Legnano) @ 18min 12sec

- Graziano Battistini (Legnano) @ 24min 28sec

- Willy Schroeders (Faema) @ 26min 4sec

- Agostino Coletto (Ignis) @ 26min 37sec

- Vito Taccone (Atala) @ 28min 53sec

- Angelo Conterno (Baratti) @ 29min 35sec

- Gabirel Mas (EMI) @ 29min 56sec

- Renzo Fontona (Legnano) @ 31min 16sec

- Ezio Pizoglio (Baratti) @ 32min 10sec

- Franco Balmamion (Bianchi) @ 35min 55sec

- Italo Mazzacurati (Carpano) @ 41min 19sec

- Gianantonio Ricco (Molteni) @ 41min 34sec

- Attilio Moresi (Baratti) @ 42min 53sec

- Hilaire Couvreur (Carpano) @ 45min 37sec

- Alfredo Sabbadin (Philco) @ 48min 38sec

- Marcel Ernzer (Gazzola) @ 54min 25sec

- Noé Conti (Ignis) @ 54min 31sec

- Vittorio Adorni (VOV) @ 55min 50sec

- Carlo Azzini (San Pellegrino) @ 58min 27sec

- Renato Giusti (Torpado) @ 1hr 4min 47sec

- Louis Rostollan (Fynsec-Helyett) @ 1hr 5min 3sec

- Antonio Bertran (EMI) @ 1hr 5min 59sec

- Marino Fontana (San Pellegrino) @ 1hr 6min 0sec

- Friedhelm Fischerkeller (Faema) @ 1hr 7min 5sec

- Piet van Est (Faema) @ 1hr 8min 2sec

- Aldo Moser (Ghigi) @ 1hr 8min 6sec

- Mies Stolker (Fynsec-Helyett) @ 1hr 9min 13sec

- Giuseppe Fallarini (Molteni) @ 1hr 13min 26sec

- Adriano Zamboni (Molteni) @ 1hr 13min 35sec

- Germano Barale (Carpano) @ 1hr 15min 7sec

- Miguel Poblet (Ignis) @ 1hr 16min 2sec

- Nino Assirelli (Fides) @ 1hr 17min 15sec

- Gabriel Company (EMI) @ 1hr 22min 5sec

- Giovanni Pettinati (Torpado) @ 1hr 22min 28sec

- Aldo Bolzan (Gazzola) @ 1hr 23min 35sec

- Edgard Sorgeloos (Faema) @ 1hr 24min 49sec

- Mario Minieri (Ghigi)@ 1hr 30min 42sec

- Armando Pellegrini (VOV) @ 1hr 39min 49sec

- Federico Galeaz (Torpado) @ 1hr 40min 15sec

- Jesus Galdeano (EMI) @ 1hr 41min 4sec

- Guido Boni (Ghigi) @ 1hr 42min 28sec

- Ernesto Bono (San Pellegrino) @ 1hr 43min 46sec

- Francisco Moreno (EMI) @ 1hr 44min 12sec

- Bruno Mealli (Bianchi) @ 1hr 45min 23sec

- Arnaldo Di Maria (Carpano) @ 1hr 52min 23sec

- Renco Accordi (Legnano) @ 1hr 54min 52sec

- Mario Bampi (Molteni) @ 1hr 57min 20sec

- Edouard Delberghe (Fynsec-Helyett) @ 1hr 58min 11sec

- Roberto Falaschi (Philco) @ 1hr 58min 26sec

- Giancarlo Manzoni (Legnano) @ 2hr 9min 22sec

- Idrio Bui (Fides) @ 2hr 9min 47sec

- Peppino Dante (Fides) @ 2hr 10min 34sec

- Salvador Rosa (EMI) @ 2hr 11min 47sec

- Luigi Arianti (Molteni) @ 2hr 18min 20sec

- Dino Bruni (Ignis) @ 2hr 19min 14sec

- Giovanni Garau (VOV) @ 2hr 19min 49sec

- Pierino Baffi (Fides) @ 2hr 20min 2sec

- Giovanni Verucchi (Torpado) @ 2hr 21min 54sec

- Pietro Chiodini (Molteni) @ 2hr 25min 2sec

- Antonio Accorsi (Torpado) @ 2hr 29min 21sec

- Santiago Montilla (EMI) @ 2hr 29min 54sec

- Nello Fabbri (Ignis) @ 2hr 30min 13sec

- Armando Casodi (Atala) @ 2hr 30min 32sec

- Waldemaro Bartolozzi (Fides) @ 2hr 31min 24sec

- Bruno Costalunga (Molteni) @ 2hr 33min 29sec

- Antonio Bailetti (Bianchi) @ 2hr 38min 26sec

- Oreste Magni (Fides) @ 2hr 39min 50sec

- Giuseppe Sartore (Bianchi) @ 2hr 48min 1sec

- Giacomo Fini (Philco) @ 2hr 54min 14sec

- Antonio Franchi (Atala) @ 2hr 55min 14sec

- Gaetano Sarazin (Bianchi) @ 2hr 55min 39sec

- Jean Stablinski (Fynsec-Helyett) @ 2hr 57min 30sec

- Gianni Ferlenghi (Gazzola) @ 2hr 58min 4sec

- Yvo Molenaers (Carpano) @ 3hr 0min 18sec

- Carlo Guarguaglini (Ignis) @ 3hr 5min 16sec

- Silvano Simonetti (Bianchi) @ 3hr 7min 22sec

- Giovanni Bettinelli (Legnano) @ 3hr 8min 42sec

- Luigi Tezza (San Pellegrino) @ 3hr 14min 3sec

- Giuseppe Pintarelli (VOV) @ 3hr 14min 45sec

- Luigi Sarti (Ghigi) @ 3hr 19min 3sec

- Jean Le Lan (Fynsec-Helyett) @ 3hr 22min 20sec

- Augusto Marcaletti (Fides) @ 2hr 36min 40sec

Climbers' Competition:

Vito Taccone (Atala): 270 points

Vito Taccone (Atala): 270 points- Gabriel Mas (Ferrys): 130

- Imerio Massignan (Legnano): 120

- Hans Junkermann (Gazzola), Jesus Galdeano (Ferrys), Angelo Conterno (Baratti): 70

Team Classification:

- Faema

- Torpado

- Ignis

- Ferrys

- Molten

1961 Giro stage results with running GC:

Saturday, May 20: Stage 1, Torino - Torino, 115 km

- Miguel Poblet: 2hr 48mn 49sec

- Franco Balmamion s.t.

- Aurelio Cestari s.t.

- Arnaldo Pambianco s.t.

- Dino Bruni @ 41sec

- Seamus Elliot s.t.

- Nello Fabbri s.t.

- Rino Benedetti @ 1min 19sec

- Silvano Ciampi s.t.

- Loris Guernieri s.t.

Sunday, May 21: Stage 2, Torino - San Remo, 185 km

![]() Major ascent: Tende

Major ascent: Tende

- Miguel Poblet: 4hr 27min 54sec

- Edgard Sorgeloos s.t.

- Martin van Geneugden s.t.

- Yvo Molenaers s.t.

- Gilbert Desmet s.t.

- Edouard Delberghe s.t.

- Dino Liveiro s.t.

- Raymond Impanis s.t.

- Silvano Ciampi s.t.

- Guillaume van Tongerloo

GC after Stage 2:

- Miguel Poblet: 7hr 20min 4sec

- Arnaldo Pambiano @ 55sec

- Franco Balmamion, Aurelio Cestari, @ 59sec

- Friedhelm Fischerkeller, Silvano Ciampi, Dino Liviero, Agostino Coletto, Gilbert Desmet @ 1min 19sec

- Dino Bruni, Nello Fabbri @ 1min 40sec

Monday, May 22: Stage 3, San Remo - Genova, 149 km

- Willy Schroeders: 3hr 28min 12sec

- Antonio Beiletti s.t.

- Marino Fontana s.t.

- Vittorio Adorni s.t.

- Germano Barale s.t.

- Idrio Bui s.t.

- Friedhelm Fischerkeller s.t.

- Peppino Dante s.t.

- Sergio Braga

- Guido Boni s.t.

GC after Stage 3:

- Miguel Poblet: 10hr 48min 59sec

- Friedhelm Fischerkeller @ 36sec

- Arnaldo Pambianco @ 55sec

- Franco Balmamion, Aurelio Cestari @ 59sec

- Silvano Ciampi, Dino Liviero, Agostino Coletto, Gilbert Desmet @ 1min 19sec

- Dino Bruni, Seamus Elliot, Nello Fabbri @ 1min 40sec

Tuesday, May 23: Stage 4, Cagliari - Cagliari, 118 km

- Oreste Magni: 2hr 50min 57sec

- Guillaume van Tongerloo s.t.

- Antonio Suarez s.t.

- Rik van Looy @ 10sec

- Rino Benedetti s.t.

- Martin van Geneugden s.t.

- Gilbert Desmet s.t.

- Gabriel Company s.t.

- Pietro Zoppas s.t.

- Mario Minieri s.t.

GC after Stage 4:

- Miguel Poblet: 13hr 40min 17sec

- Friedhelm Fischerkeller @ 25sec

- Franco Balmamion, Aurelio Cestari @ 48sec

- Arnaldo Pambianco @ 55sec

- Silvano Ciampi, Dino Liviero, Agostino Coletto, Gilbert Desmet @ 1min 19sec

- Dino Bruni, Seamus Elliot, Nello Fabbri @ 1min 40sec

Wednesday, May 24: Stage 5, Marsala - Palermo, 144 km

![]() Major ascent: San Pellegrino

Major ascent: San Pellegrino

- Louis Proost: 3hr 52min 56sec

- Willy Schroeders s.t.

- Giuseppe Tanucci s.t.

- Raymond Impanis s.t.

- Jesus Galdeano s.t.

- Jean Stablinski s.t.

- Mies Stolker s.t.

- Martin van Geneugden @ 26sec

- Rino Benedetti s.t.

- Adriano Zamboni s.t.

GC after Stage 5:

- Miguel Poblet: 17hr 33min 49sec

- Friedhelm Fischerkeller @ 25sec

- Franco Balmamion @ 48sec

- Armando Pambianco @ 55sec

- Silvano Ciampi, Dino Liviero, Agostino Coletto @ 1min 19sec

- Mies Stolker @ 1min 37sec

- Dino Bruni, Seamus Elliot, Nello Fabbri @ 1min 40sec

Friday, May 26: Stage 6, Palermo - Milazzo, 224 km

- Nino Defilippis: 5hr 57min 25sec

- Armand Desmet s.t.

- Willy Vannitsen s.t.

- Ezio Pizzoglio s.t.

- Rik van Looy s.t.

- Dino Bruni s.t.

- Marino Fontana s.t.

- Vito Favero s.t.

- Ernesto Bono s.t.

- Nello Velucchi s.t.

GC after Stage 6:

- Miguel Poblet: 23hr 31min 14sec

- Friedhelm Fischerkeller @ 25sec

- Franco Balmamion @ 48sec

- Arnaldo Pambianco @ 55sec

- Silvano Ciampi, Dino Liviero, Agostino Coletto @ 1min 19sec

- Mies Stolker @ 1min 37sec

- Dino Bruni, Seamus Elliot, Nello Fabbri @ 1min 40sec

Saturday, May 27: Stage 7, Reggio Calabria - Cosenza, 221 km

![]() Major Ascent: Acquabona

Major Ascent: Acquabona

- Antonio Suarez: 6hr 9min 27sec

- Rik van Looy @ 1min 52sec

- Edgard Sorgeloos s.t.

- Angelo Conterno s.t.

- Imerio Massignan s.t.

- Freidhelm Fischerkeller s.t.

- Charly Gaul s.t.

- Jacques Anquetil s.t.

- Arnaldo Pambianco s.t.

- Louis Rostollan s.t.

GC after Stage 7:

- Antonio Suarez: 29hr 42min 44sec

- Friedhelm Fischerkeller @ 14sec

- Franco Balmamion @ 37sec

- Arnaldo Pambianco @ 44sec

- Jacques Anquetil @ 1min 56sec

- Angelo Conterno, Rik van Looy, Charly Gaul, Hans Junkermann @ 2min 7sec

- Louis Rostollan @ 2min 29sec

Sunday, May 28: Stage 8, Cosenza - Taranto, 227 km

- Piet van Est: 6hr 33min 9sec

- Jean Stablinski s.t.

- Ernesto Bono s.t.

- Willy Schroeders s.t.

- Jesus Galdeano s.t.

- Hilaire Couvreur s.t.

- Guillaume van Tongerloo s.t.

- Nunzio Pelliciari @ 3min 5sec

- Rik van Looy @ 8min 6sec

- Antonio Bailetti s.t.

GC after Stage 8:

- Guillaume van Tongerloo: 35hr 21min 11sec

- Antonio Suarez @ 2min 48sec

- Friedhelm Fischerkeller @ 3min 2sec

- Franco Balmamion @ 3min 25sec

- Jacques Anquetil @ 4min 44sec

- Angelo Conterno, Rik van Looy, Charly Gaul, Hans Junkermann @ 4min 55sec

- Louis Rostollan @ 5min 8sec

Monday, May 29: Stage 9, Taranto - Bari 53 km individual time trial

- Jacques Anquetil: 1hr 8min 1sec

- Guillaume van Tongerloo @ 2min 52sec

- Antonio Suarez s.t.

- Vittorio Adorni @ 3min 0sec

- Graziano Battistini @ 3min 33sec

- Rik van Looy @ 3min 36sec

- Antonio Bailetti @ 3min 38sec

- Renzo Fontona @ 3min 47sec

- Franco Balmamion @ 3min 53sec

- Nino Defilippis s.t.

- Migeul Poblet @ 4min 1sec

- Guido Carlesi @ 4min 13sec

- Aldo Kazianka @ 4min 24sec

- Luigi Arienti @ 4min 26sec

GC after stage 9:

- Guillaume van Tongerloo: 36hr 32min 4sec

- Jacques Anquetil @ 1min 52sec

- Antonio Suarez @ 2min 48sec

- Franco Balmamion @ 4min 26sec

- Friedhelm Fischerkeller @ 5min 25sec

- Rik van Looy @ 5min 39sec

- Miguel Poblet @ 5min 44sec

- Hans Junkermann @ 6min 53sec

- Arnaldo Pambianco @ 7min 7sec

- Charly Gaul @ 7min 37sec

Tuesday, May 30: Stage 10, Bari - Potenza, 140 km

![]() Major ascent: Pozzano

Major ascent: Pozzano

- Vito Taccone: 4hr 2min 43sec

- Hans Junkermann s.t.

- Adriano Zamboni @ 38sec

- Miguel Poblet @ 40sec

- Mies Stolker s.t.

- Gilbert Desmet s.t.

- Federico Bahamontes s.t.

- Guido Carlesi @ 2min 2sec

- Willy Schroeders s.t.

- Federico Galeaz s.t.

GC after Stage 10:

- Jacques Anquetil: 41hr 38min 41sec

- Antonio Suarez @ 56sec

- Guillaume van Tongerloo @ 1min 42sec

- Franco Balmamion @ 2min 34sec

- Hans Junkermann @ 2mn 59sec

- Miguel Poblet @ 3min 20sec

- Friedhelm Fischerkeller @ 3min 33sec

- Rik van Looy @ 3min 47sec

- Arnaldo Pambianco @ 5min 15sec

- Charly Gaul @ 5min 45sec

Wednesday, May 31: Stage 11, Potenza - Teano, 252 km

![]() Major ascent: Pietrastretta

Major ascent: Pietrastretta

- Pietro Chiodini: 7hr 6min 58sec

- Dino Liviero s.t.

- Seamus Elliot s.t.

- Antonio Bertran s.t.

- Armando Pellegrini s.t.

- Alfredo Sabbadin s.t.

- Germano Barale s.t.

- Carlo Brugnami s.t.

- Renato Giusti s.t.

- Noé Conti s.t.

GC after Stage 11:

- Jacques Anquetil: 48hr 45min 38sec

- Antonio Suarez @ 56sec

- Guillaume van Tongerloo @ 1min 42sec

- Arnaldo Pambianco @ 2min 16sec

- Hans Junkermann @ 2min 59sec

- Miguel Poblet @ 3min 30sec

- Friedhelm Fischerkeller @ 3min 33sec

- Rik van Looy @ 3min 47sec

- Guido Carlesi @ 4min 23sec

- Carlo Brugnami @ 5min 4sec

Thursday, June 1: Stage 12, Gaeta - Roma, 149 km

- Renato Giusti: 3hr 56min 31sec

- Bruno Mealli s.t.

- Noé Conti s.t.

- Giovanni Garau s.t.

- Giuseppe Sartore s.t.

- Luigi Arienti @ 31sec

- Gilbert Desmet @ 2min 9sec

- Arnaldo Pambianco s.t.

- Carlo Azzini s.t.

- Rino Benedetti @ 3min 7sec

GC after Stage 12:

- Jacques Anquetil: 52hr 48min 16sec

- Antonio Suarez @ 56sec

- Arnaldo Pambianco @ 1min 15sec

- Guillaume van Tongerloo @ 1min 42sec

- Hans Junkermann @ 2min 36sec

- Miguel Poblet @ 3min 30sec

- Friedhelm Fischerkeller @ 3min 33sec

- Rik van looy @ 3min 47sec

- Guido Carlesi @ 4min 23sec

- Carlo Brugnami @ 5min 4sec

Friday, June 2: Stage 13, Mentana - Castelfidardo, 279 km

![]() Major ascent: Fornaci

Major ascent: Fornaci

- Rik van Looy: 7hr 58min 27sec

- Antonio Suarez @ 4sec

- Guido Carlesi s.t.

- Adriano Zamboni s.t.

- Vito Taccone s.t.

- Hans Junkermann s.t.

- Willy Schroeders s.t.

- Jacques Anquetil s.t.

- Charly Gaul s.t.

- Arnaldo Pambianco s.t.

GC after stage 13:

- Jacques Anquetil: 60hr 46min 47sec

- Antonio Suarez @ 46sec

- Arnaldo Pambianco @ 1min 18sec

- Hans Junkermann @ 2min 59sec

- Guillaume van Tongerloo @ 3min 2sec

- Rik van Looy @ 3min 34sec

- Guido Carlesi @ 4min 23sec

- Miguel Poblet @ 4min 50sec

- Charly Gaul @ 5min 45sec

- Carlo Brugnami @ 6min 26sec

Saturday, June 3: Stage 14, Ancona - Firenze, 250 km

![]() Major ascent: Muraglione

Major ascent: Muraglione

- Silvano Ciampi: 7hr 26min 46sec

- Dino Liviero s.t.

- Armando Pellegrini s.t.

- Renato Giusti s.t.

- Mario Bampi s.t.

- Marino Fontana s.t.

- Arnaldo Pambianco s.t.

- Guido Carlesi and 29 other riders @ 1min 42sec

GC after Stage 14:

- Arnaldo Pambianco: 68hr 14min 51sec

- Jacques Anquetil @ 24sec

- Antonio Suarez @ 1min 20sec

- Hans Junkermann @ 3min 23sec

- Guillaume van Tongerloo @ 3min 26sec

- Rik van Looy @ 4min 7sec

- Guido Carlesi @ 4min 37sec

- Charly Gaul @ 6min 9sec

- Silvano Ciampi @ 6min 45sec

- Carlo Brugnami @ 6min 50sec

Sunday, June 4: Stage 15: Firenze - Modena, 178 km

![]() Major ascents: Le Piastre, Abetone

Major ascents: Le Piastre, Abetone

- Rik van Looy: 5hr 4min 56sec

- Edgard Sorgeloos s.t.

- Antonio Suarez s.t.

- Guido Carlesi s.t.

- Adriano Zamboni s.t.

- Nino Defilippis s.t.

- Piet van Est s.t.

- Edouard Delberghe s.t.

- Jesus Galdeano s.t.

- Vito Taccone s.t.

GC after Stage 15:

- Arnaldo Pambianco: 73hr 19min 47sec

- Jacques Anquetil @ 24sec

- Antonio Suarez @ 1min 20sec

- Hans Junkermann @ 3min 23sec

- Guillaume van Tongerloo @ 3min 26sec

- Rik van Looy @ 4min 7sec

- Guido Carlesi @ 4min 47sec

- Charly Gaul @ 6min 9sec

- Nino Defilippis @ 7min 28sec

- Imerio Massignan @ 9min 19sec

Monday, June 5: Stage 16, Mondena - Vicenza, 207 km

- Adriano Zamboni: 5hr 14min 19sec

- Renato Giusti @ 4sec

- Rino Benedetti s.t.

- Willy Schroeders s.t.

- Marino Fontana s.t.

- Dino Liviero s.t.

- Nino Defilippis s.t.

- Ezio Pizzolgio s.t.

- Antonio Bailetti @ 24sec

- Arnaldo Di Maria s.t.

GC after Stage 16:

- Arnaldo Pambianco: 78hr 38min 11sec

- Jacques Anquetil @ 24sec

- Antonio Suarez @ 1min 20sec

- Hans Junkermann @ 3min 23sec

- Nino Defilippis @ 3min 25sec

- Guillaume van Tongerloo @ 3min 26sec

- Rik van Looy @ 4min 7sec

- Guido Carlesi @ 4min 47sec

- Charly Gaul @ 6min 9sec

- Willy Schroeders @ 7min 53sec

Tuesday, June 6: Stage 17, Vicenza - Trieste, 204 km

- Rik van Looy: 5hr 4min 56sec

- Catullo Ciacci s.t.

- Rino Benedetti s.t.

- Arrigo Padovan s.t.

- Bruno Costalunga s.t.

- Renato Giusti s.t.

- Renzo Fontona s.t.

- Dino Livieri s.t.

- Oreste Magni s.t.

- Piet van Est s.t.

GC after Stage 17:

- Arnaldo Pambianco: 83hr 43min 7sec

- Jacques Anquetil @ 44sec

- Antonio Suarez @ 1min 20sec

- Nino Defilippis @ 3min 25sec

- Hans Junkermann @ 3min 43sec

- Guillaume van Tongerloo @ 3min 46sec

- Rik van Looy @ 4min 7sec

- Guido Carlesi @ 5min 7sec

- Charly Gaul @ 6min 29sec

- Willy Schroeders @ 7min 53sec

Thursday, June 8: Stage 18, Trieste - Vittorio Veneto, 161 km

- Renato Giusti: 3hr 45min 1sec

- Willy Derboven s.t.

- Bruno Costalunga s.t.

- Aldo Kazianka s.t.

- Mario Bampi s.t.

- Luigi Tezza s.t.

- Yvo Molenaers s.t.

- Antonio Bertran s.t.

- André Cloarec s.t.

- Giuseppe Pintarelli s.t.

GC after Stage 18:

- Arnaldo Pambianco: 87hr 36min 55sec

- Jacques Anquetil @ 44sec

- Antonio Suarez @ 1min 20sec

- Nino Defilippis @ 3min 25sec

- Hans Junkermann @ 3min 43sec

- Guillaume van Tongerloo @ 3min 46sec

- Rik van Looy @ 4min 7sec

- Guido Carlesi @ 5min 7sec

- Charly Gaul @ 6min 29sec

- Willy Schroeders @ 7min 53sec

Friday, June 9: Stage 19, Vittorio Veneto - Trento, 249 km

![]() Major ascents: Falzarego, Pordoi

Major ascents: Falzarego, Pordoi

- Willy Schroeders: 6hr 50min 0sec

- Carlo Brugnami s.t.

- Ezio Pizzoglio s.t.

- Franco Balmamaion s.t.

- Guillaume van Tongerloo s.t.

- Graziano Battistini s.t.

- Rik van Looy @ 2min 40sec

- Adriano Zamboni s.t.

- Imerio Massignan s.t.

- Angelo Conterno s.t.

GC after Stage 19:

- Arnaldo Pambianco: 94hr 29min 35sec

- Jacques Anquetil @ 44sec

- Guillaume van Tongerloo @ 1min 6sec

- Antonio Suarez @ 1min 20sec

- Nino Defilippis @ 3min 25sec

- Hans Junkermann @ 3min 43sec

- Rik van Looy @ 4min 7sec

- Guido Calesi @ 5min 7sec

- Willy Schroeders @ 5min 13sec

- Charly Gaul @ 6min 29sec

Saturday, June 10: Stage 20: Trento - Bormio, 275 km

![]() Major ascents: Pennes, Giovo, Stelvio

Major ascents: Pennes, Giovo, Stelvio

- Charly Gaul: 10hr 42min 0sec

- Arnaldo Pambianco @ 2min 7sec

- Antonio Suarez @ 3min 4sec

- Guido Carlesi @ 3min 8sec

- Jacques Anquetil s.t.

- Carlo Brugnami @ 4min 2sec

- Graziano Battistini @ 4min 30sec

- Ernesto Bono @ 4min 39sec

- Ezio Pizzoglio @ 7min 40sec

- Renzo Fontona @ 8min 41sec

GC after Stage 20:

- Arnaldo Pambianco: 105hr 12min 42sec

- Jacques Anquetil @ 3min 45sec

- Antonio Suarez @ 4min 17sec

- Charly Gaul @ 4min 22sec

- Guido Carlesi @ 8min 8sec

- Hans Junkermann @ 12min 25sec

- Rik van Looy @ 12min 38sec

- Guillaume van Tongerloo @ 14min 18sec

- Carlo Brugnami @ 16min 5sec

- Nino Defilippis @ 16min 23sec

Sunday, June 11: 21st and Final Stage, Bormio - Milano, 214 km

- Miguel Poblet: 6hr 11min 46sec

- Rik van Looy s.t.

- Dino Bruni s.t.

- Luigi Sarti s.t.

- Armando Pellegrini s.t.

- Pietro Chiodini s.t.

- Adriano Zamboni s.t.

- Edgard Sorgeloos s.t.

- Renato Giusti s.t.

- Luigi Arianti s.t.

The Story of the 1961 Giro d'Italia

This excerpt is from "The Story of the Giro d'Italia", Volume 1. If you enjoy it we hope you will consider purchasing the book, either print, eBook or audiobook. The Amazon link here will make the purchase easy.

Anquetil still yearned for the elusive and difficult Giro-Tour double. His early-season condition looked good. He won Paris–Nice and the time trial in the Tour of Romandie.

Rik van Looy might be the greatest classics rider of all time, but he too was full of unrequited desire. He ended up winning 379 professional road races, but up until now he still had not won a Grand Tour. Van Looy was again wearing the World Champion’s Rainbow Jersey and again set out to fill in that gap in his palmarès.

A young rider from Piedmont had established himself as one of the finest amateurs racing in northern Italy. Bianchi, looking for a good young rider to anchor their team in the post-Coppi era, signed Franco Balmamion to be their team leader for the Giro. Balmamion was in the demographic cohort born just before the war, growing up in the suffocating poverty of post-war Italy. For Balmamion and his family, finding the money for a racing bike was out of the question. An employer gave the young athlete the wheels he needed to compete. This still happens in Italy. A young rider interested in cycling can often find free equipment and coaching from clubs and friends interested in fostering young hopefuls.

Balmamion was only 21 when he was thrust into the role of a Grand Tour team leader. During this era Italy often took her gifted athletes when they were far too young and threw them into the punishing arena of stage racing. Like Defilippis, Balmamion was made for the sport. He couldn’t sprint and he couldn’t jump away from the others on a steep ascent but he could climb well and he was one of those lucky riders who could take a three-week race without breaking down. He had another gift. Balmamion possessed a superb tactical and strategic mind which allowed him to exploit his own abilities and know when others were on the verge of collapse.

Torriani’s design of the 1961 Giro was to be a celebration of the one-hundredth anniversary of the founding of the Kingdom of Italy. After several stages that took the Giro to Genoa, there was to be the Giro’s first-ever stage in Sardinia. Next, in homage to Garibaldi, a boat trip to Marsala for a couple of days of racing on the island of Sicily. Then the peloton would race its way up the boot with two days in the Dolomites before the final stage to Milan. Along the way the Giro would visit cities that had played a crucial part in the struggle to unify Italy, including Teano and Florence. At 4,004 kilometers divided into 21 stages, it was certain to be a long, hard Giro with an average stage length back up to 191 kilometers.

As part of Italian centenary commemoration, the Giro’s first stage was actually three mini-stages departing and arriving at Turin, Italy’s first capitol.

During the trittico tricolore, young Balmamion took off on the Maddalena and astonishingly (to the other riders who probably knew nothing of this neo-pro) crested the mountain alone and was only caught within a few kilometers of the finish line by three other riders. Miguel Poblet beat him to the line and took the first Pink Jersey while Arnaldo Pambianco was second and Balmamion third. By the end of the third mini-stage, Poblet was still in pink with Balmamion second.

During the races through Piedmont, Liguria, Sardinia and Sicily, Poblet kept the lead, but when the riders had to cover the rough country of Calabria he had to give it up to compatriot (and Vuelta winner) Antonio Suárez. The Spanish Road Champion held the maglia rosa by the narrowest of gaps, just fourteen seconds over van Looy gregario Friedhelm Fischerkeller.

For Anquetil, taking the Pink Jersey in the middle stages was a three-step affair. In stage eight, a break containing Anquetil’s loyal gregario Jean Stablinski and several other capable journeymen was first into Taranto by three minutes. That gave the Pink Jersey to one of the escapees, Guillaume van Tongerloo, yet another Faema teammate of van Looy’s. Arnaldo Pambianco crashed badly but with the aid of his team, which waited for him, managed to finish only two minutes behind the Anquetil group.

Nini Defilippis wins stage 6 in Milazzo

Anquetil won the stage nine time trial, a 53-kilometer trip to Bari. Van Tongerloo, surely powered by his ownership of the maglia rosa, was second, about three minutes slower than Anquetil. The Belgian stayed at the top of the leaderboard with Anquetil about two minutes back.

Stage ten, going from Bari to Potenza, broke the peloton into several large pieces with most of the contenders getting into the Anquetil group. Anquetil was now the leader.

The General Classification now stood thus:

1. Jacques Anquetil

2. Antonio Suárez @ 56 seconds

3. Guillaume van Tongerloo @ 1 minute 42 seconds

4. Franco Balmon @ 2 minutes 34 seconds

5. Hans Junkermann @ 2 minutes 59 seconds

Stage eleven broke things up further. A huge split put more than half the field out of likely contention. Among those in the unfortunate group finishing 20 minutes after stage winner Pietro Chiodini were Balmamion, Stablinski, Impanis and Bahamontes.

Stage fourteen covered 250 kilometers from Ancona on the Adriatic to Florence. A break of seven flew the coop, among them Pambianco. Why Pambianco, then sitting only 78 seconds behind Anquetil in third place, was allowed to get away is a mystery, but get away he did. The pack came into Florence 1 minute 42 seconds after the break. Anquetil’s inattention cost him the lead, which migrated to Pambianco.

Pambianco’s move to the top may have been a momentary surprise, but it might be considered the fulfillment of what his talent had promised. He had been on Italy’s Melbourne Olympic team, been amateur Italian Road Champion and had come in second in the worlds before turning pro. He became a gregario first for Baldini and then for Nencini. In 1960 Pambianco had clearly arrived when he finished seventh in both the Giro and the Tour.

Pambianco was a quality rider but this wasn’t much of a lead, especially with Charly Gaul was still lurking in the peloton, waiting to blow up the race in the Dolomites. Pambianco could at least take comfort in knowing Anquetil had no more time trials:

1. Arnaldo Pambianco

2. Jacques Anquetil @ 24 seconds

3. Antonio Suárez @ 1 minute 20 seconds

4. Hans Junkermann @ 3 minutes 23 seconds

5. Guillaume van Tongerloo @ 3 minutes 26 seconds

6. Rik van Looy @ 4 minutes 7 seconds

With the exception of the twenty seconds Anquetil lost in stage seventeen, the peloton reached Vittorio Veneto and the beginning of the high mountains with the General Classification much as it had been since Pambianco took the lead.

Stage nineteen was 249 kilometers of Dolomite roads with the Falzarego and Pordoi passes to break up the field. No effect. It was still Pambianco in pink with Anquetil at 44 seconds.

That left the penultimate stage as a last chance to change the standings. 275 kilometers long, it included 3 major passes: the Pennes, the Giovo and the Stelvio. Van Looy was sitting in seventh place, only 4 minutes 7 seconds behind Pambianco. On a stage of this length and difficulty, a good rider having a great day might erase those four minutes.

Van Looy gambled and gambled big by taking off early in the stage. He was the first over the Giovo and when he reached the Stelvio he was alone and eight minutes ahead of his nearest chasers. The Belgian might indeed have been on the verge of an incredible coup. But, the north face of the Stelvio is 26.5 kilometers long with 48 switchbacks that seem to go on forever. Part way up the snow-covered mountain he tore a muscle in his leg. After that, he didn’t have a chance. Flying up the mountain, spinning like a sewing machine, Charly Gaul was in his element. Soaring between the walls of snow he swept by the struggling Belgian and was first over the top. He raced for Bormio and won the stage. It was to be his last great road victory in Italy and one of the last of his career.

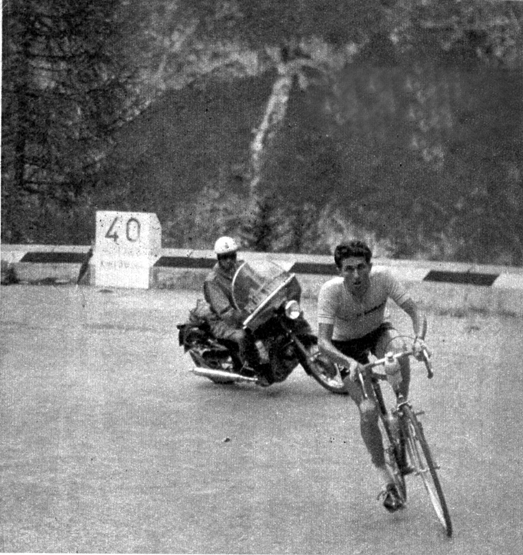

Pambianco on the Stelvio (at least I think this is the Stelvio with a numbered switchback)

Van Looy lost eight and a half minutes to Pambianco who had finished a little over two minutes behind Gaul. Anquetil lost about one minute (plus about two more in time bonuses) to Pambianco making the Italian the sure and rightful winner in Milan.

Anquetil, blocked again in his attempt to do the big double announced a very high goal for the Tour. He would take the lead on the first day and hold it until the end. The Tour’s first day was a split stage with a time trial in the afternoon. Anquetil was true to his word. He took the Yellow Jersey the first day and never let it go. His mastery was so profound that second-place Guido Carlesi was over twelve minutes in arrears by the time the Tour reached Paris. Fans complained that Anquetil had so dominated the race that he suffocated it. If they had wanted to watch a hot, competitive race they should have gone to Italy that year.

Arnaldo Pambianco celebrates his victory

Final 1961 Giro d’Italia General Classification:

1. Arnaldo Pambianco (Fides) 111 hours 25 minutes 28 seconds

2. Jacques Anquetil (Fynsec-Helyett) @ 3 minutes 45 seconds

3. Antonio Suárez (EMI) @ 4 minutes 17 seconds

4. Charly Gaul (Gazzola) @ 4 minutes 22 seconds

5. Guido Carlesi (Philco) @ 8 minutes 8 seconds

Climbers’ Competition:

1. Vito Taccone (Atala)

2. Gabriel Mas (EMI)

3. Imerio Massignan (Legnano)

After retiring in 1965, Gaul started a bar (which makes one wonder how much money a top pro actually made and if the pay were decent, where did Gaul’s dough go?), but after his first wife died he turned to alcohol and eventually lost the bar. He became a recluse, living in a hut in the Ardennes forest, a confused and forgetful, bearded, potbellied man no one would recognize as one of the most feared riders of his era. In the 1980s he began to come around and started showing up at races, even becoming a bit of a mentor to Marco Pantani, who’d sought him out in the winter of 1997–1998. But he seemed befuddled to the end. One can’t help but wonder if this were the price to be paid for the massive quantities of drugs and post-retirement alcohol he consumed. Charly Gaul passed away in 2005.

.