1966 Giro d'Italia

49th edition: May 18 - June 9

Results, stages with running GC, photos, video and history

1965 Giro | 1967 Giro | Giro d'Italia Database | 1966 Giro Quick Facts | 1966 Giro d'Italia Final GC | Stage results with running GC | The Story of the 1966 Giro d'Italia | Video

Les Woodland's book The Olympics' 50 Craziest Stories: A Five Ring Circus is available in print, Kindle eBook & audiobook versions. To get your copy, just click on the Amazon link on the right.

3,976 km raced at an average speed of 35.74 km/hr

100 starters and 83 classified finishers

Jacques Anquetil returned for an attempt to win the Giro a third time.

Amid complex sponsorship politics Anquetil suffered an unfortunately timed flat tire and was out of the running after the first stage.

Anquetil threw his weight behind Gianni Motta, who was enjoying the form of his life.

Motta rode in commanding fashion over the Dolomites to secure his only Giro victory.

1966 Giro d'Italia Complete Final General Classification:

Gianni Motta (Molteni) 111hr 10min 48sec

Gianni Motta (Molteni) 111hr 10min 48sec- Italo Zilioli (Sanson) @ 3min 57sec

- Jacques Anquetil (Ford) @ 4min 40sec

- Julio Jiménez (Ford) @ 5min 44sec

- Felice Gimondi (Salvarani) @ 6min 47sec

- Franco Balmamion (Sanson) @ 7min 27sec

- Vittorio Adorni (Salvarani) @ 8min 0sec

- Franco Bitossi (Filotex) @ 9min 24sec

- Vito Taccone (Vittadello) @ 11min 42sec

- Rolf Maurer (Filotex) @ 20min 28sec

- Dino Zandegù (Bianchi) @ 24min 4sec

- Silvano Schiavon (Legnano) @ 26min 0sec

- Rudi Altig (Molteni) @ 26min 43sec

- Marcello Mugnaini (Filotex) @ 27min 18sec

- Renzo Fontona (Mainetti) @ 30min 52sec

- Graziano Battistini (Vittadello) @ 31min 47sec

- Joseph Huysmans (Mann-Grundig) @ 37min 36sec

- Ugo Colombo (Filotex) @ 38min 34sec

- Imerio Massignan (Bianchi) @ 39min 10sec

- Michele Dancelli (Molteni) @ 48min 35sec

- Flaviano Vicentini (Legnano) @ 49min 16sec

- Roberto Poggiali (Poggiali) @ 59min 20sec

- Angelo Ottaviani (Vittadello) @ 1hr 4min 50sec

- Franco Bodrero (Legnano) @ 1hr 5min 58sec

- Bruno Mealli (Bianchi) @ 1hr 11min 42sec

- Giancarlo Ferretti (Sanson) @ 1hr 12min 36sec

- Albano Negro (Bianchi) @ 1hr 18min 30sec

- Mario Maino (Bianchi) @ 1hr 30min 55sec

- Lino Farisato (Mainetti) @ 1hr 22min 48sec

- Pietro Scandelli (Molteni) @ 1hr 27min 0sec

- Carlo Chiappano (Sanson) @ 1hr 32min 16sec

- André Messelis (Mann-Grundig) @ 1hr 33min 18sec

- Marino Fontana (Mainetti) @ 1hr 33min 43sec

- Pietro Partesotti (Salvarani) @ 1hr 34min 9sec

- Arnaldo Pambianco (Salvarani) @ 1hr 34min 35sec

- Giovanni Knapp (Vittadello) @ 1hr 34min 48sec

- Carmine Preziosi (Bianchi) @ 1hr 35min 3sec

- Ambrogio Portalupi (Vittadello) @ 1hr 40min 37sec

- Luciano Armani (Salvarani) @ 1hr 44min 13sec

- Vic Denson (Ford) @ 1hr 45min 51sec

- Jean Stablinski (Ford) @ 1hr 49min 45sec

- Renzo Baldan (Vittadello) @ 1hr 59min 22sec

- Franceso Mele (Bianchi) @ 1hr 59min 25sec

- Luciano Sambi (Legnano) @ 2hr 2min 58sec

- Gianpaolo Cucchietti (Sanson) @ 2hr 3min 27sec

- Emilio Casalini (Legnano) @ 2hr 5min 4sec

- Egidio Cornale (Mainetti) @ 2hr 6min 27sec

- Marino Basso (Mainetti) @ 2hr 9min 32sec

- Bruno Centomo (Legnano) @ 2hr 10min 3sec

- Giorgio Destro (Mainetti) @ 2hr 15min 22sec

- Angelo Bugini (Legnano) @ 2hr 16min 30sec

- Antoine Houbrechts (Mann-Grundig) @ 2hr 19min 1sec

- Vendramino Bariviera (Sanson) @ 2hr 20min 22sec

- Antonio Bailetti (Bianchi) @ 2hr 21min 15sec

- Mario Da Dalt (Sanson) @ 2hr 21min 53sec

- Raffaele Marcoli (Sanson) @ 2hr 25min 33sec

- Adriano Durante (Salvarani) @ 2hr 26min 10sec

- Giuseppe Fezzardi (Molteni) @ 2hr 30min 31sec

- Roberto Ballini (Filotex) @ 2hr 31min 32sec

- Marino Vigna (Vittadello) @ 2hr 33min 14sec

- Paolo Manucci (Filotex) @ 2hr 33min 37sec

- Jean Graczyk (Ford) @ 2hr 33min 53sec

- Lucillo Lievore (Mainetti) @ 2hr 34min 31sec

- Jan Nolmans (Mann-Grundig) @ 2hr 37min 4sec

- René Binggeli (Molteni) @ 2hr 38min 5sec

- Pietro Campagnari (Mainetti) @ 2hr 40min 1sec

- Jean Milesi (Ford) @ 2hr 41min 16sec

- Pierre Everaert (Ford) @ 2hr 43min 10sec

- Giuseppe Sartore (Sanson) @ 2hr 46min 40sec

- Anatole Novak (Ford) @ 2hr 54min 44sec

- Severino Andreoli (Vittadello) @ 2hr 55min 4sec

- Giuseppe Grassi (Filotex) @ 2hr 56min 27sec

- Jozef Boons (Mann-Grundig)@ 2hr 56min 30sec

- Aldo Pifferi (Vittadello) @ 2hr 58min 53sec

- Gianpiero Macchi (Legnano) @ 3hr 1min 7sec

- Mario Anni (Molteni) @ 3hr 6min 21sec

- Mario Minieri (Salvarani) @ 3hr 7min 6sec

- Remo Stefanoni (Molteni) @ 3hr 8min 14sec

- Gérard Thielin (Ford) @ 3hr 11min 22sec

- Renato Bonso (Mainetti) @ 3hr 39min 47sec

- Giacomo Fornoni (Molteni) @ 3hr 43min 14sec

- Enrico Massignan (Bianchi) @ 3hr 54min 19sec

- Paolo Gelli (Filotex) @ 4hr 11min 23sec

Climbers' Competition:

Franco Bitossi (Filotex): 490 points

Franco Bitossi (Filotex): 490 points- Julio Jiménez (Ford): 320

- Gianni Motta (Molteni): 160

- Italo Zilioli (Sanson): 150

- Silvano Schiavon (Legnano): 120

Points Competition:

Gianni Motta (Molteni): 228 points

Gianni Motta (Molteni): 228 points- Rudi Altig (Molteni): 162

- Vito Taccone (Vittadello): 152

- Franco Bitossi (Filotex): 147

- Dino Zandegù (Bianchi): 143

Team Classification: Molteni

1966 Giro stage results with running GC:

Wednesday, May 18: Stage 1, Monte Carlo - Diano Marina, 140 km

![]() Major ascent: Colle San Bartolomeo

Major ascent: Colle San Bartolomeo

- Vito Taccone: 3hr 40min 22sec

- Bruno Mealli s.t.

- Dino Zandegù s.t.

- Felice Gimondi s.t.

- Rudi Altig s.t.

- Roberto Preziosi s.t.

- Italo Zilioli s.t.

- Gianni Motta s.t.

- Mario Fontana s.t.

- Franco Bitossi s.t.

Thursday, May 19: Stage 2, Imperia - Monesi, 60 km

![]() Major ascents: Nava, Monesi

Major ascents: Nava, Monesi

- Julio Jiménez: 1hr 57min 7sec

- Gianni Motta @ 1min 23sec

- Felice Gimondi @ 1mn 25sec

- Rolf Maurer s.t.

- Jacques Anquetil s.t.

- Marcello Mugnaini s.t.

- Vittorio Adorni @ 1min 32sec

- Franco Balmamion @ 1min 36sec

- Franco Bitossi @ 1min 39sec

- Italo Zilioli @ 1min 44sec

GC after Stage 2:

- Julio Jiménez: 5hr 46min 29sec

- Gianni Motta @ 1min 23sec

- Felice Gimondi, Rolf Maurer @ 1min25sec

- Vittorio Adorni @ 1min 32sec

- Franco Balmamion @ 1mn 36sec

- Franco Bitossi @ 1min 38sec

- Italo Zilioli @ 1min 44sec

- Roberto Preziosi @ 2min 29sec

- Guido De Rosso @ 2min 32sec

Friday, May 20: Stage 3, Monesi - Genova, 120 km

- Severino Andreoli: 2hr 27min 27sec

- Vittorio Adorni s.t.

- Jan Nolmans s.t.

- Michele Dancelli s.t.

- Marino Basso s.t.

- Jean Graczyk s.t.

- Jozef Boons s.t.

- Mario Fontana

- Mario Da Dalt s.t.

- Gianni Motta s.t.

GC after Stage 3:

- Julio Jiménez: 8hr 13min 56sec

- Gianni Motta @ 1min 23sec

- Vittorio Adorni @ 1min 32sec

- Franco Balmamion @ 1min 36sec

- Italo Zilioli @ 1min 44sec

- Guido De Rosso @ 2min 32sec

- Vito Taccone @ 2min 51sec

- Felice Gimondi, Rolf Maurer @ 3min 1sec

- Franco Bitossi @ 3min 15sec

Saturday, May 21: Stage 4, Genova - Viareggio, 251 km

![]() Major ascents: Bocco, Cisa

Major ascents: Bocco, Cisa

- Giovanni Knapp: 6hr 48min 39sec

- Roberto Poggiali s.t.

- Antonio Bailetti @ 2sec

- Gianni Motta @ 55sec

- Vito Taccone s.t.

- Jean Graczyk s,t,

- Constant Jongen s.t.

- Flaviano Vicentini s.t.

- Giuseppe Grassi s.t.

- Pietro Campagnari s.t.

GC after Stage 4:

- Julio Jiménez: 15hr 3min 30sec

- Gianni Motta @ 1min 23sec

- Vittorio Adorni @ 1min 32sec

- Franco Balmamion @ 1min 38sec

- Italo Zilioli @ 1min 44sec

- Guido De Rosso @ 2min 32sec

- Vito Taccone @ 2min 51sec

- Felice Gimondi, Rolf Maurer @ 3min 1sec

- Franco Bitossi @ 3min 15sec

Sunday, May 22: Stage 5, Viareggio - Chianciano Terme, 222 km

- Vendramino Bariviera: 3hr 40min 22sec

- Vito Taccone @ 1sec

- Ambrogio Portalupi s.t.

- Pietro Partesotti @ 2sec

- Flaviano Vicentini s.t.

- Giancarlo Polidori s.t.

- Renzo Fontona s.t.

- Silvano Schiavon s.t.

- Joseph Huysmans s.t.

- Guido De Rosso @ 4sec

GC after Stage 5:

- Julio Jiménez: 21hr 24min 55sec

- Guido De Rosso @ 43sec

- Vito Taccone @ 58sec

- Gianni Motta @ 1min 17sec

- Vittorio Adorni @ 1min 26sec

- Franco Balmamion @ 1min 30sec

- Italo Zilioli @ 1min 38sec

- Felice Gimondi, Rolf Maurer @ 2min 55sec

- Franco Bitossi @ 3min 8sec

Monday, May 23: Stage 6, Chianciano Terme - Roma, 226 km

- Raffaele Marcoli: 6hr 7min 21sec

- Rudi Altig s/t/

- Michele Dancelli s.t.

- Dino Zandegù s.t.

- Jean Graczyk s.t.

- Adriano Durante s.t.

- Franco Bitossi s.t.

- Silvano Schiavon @ 27sec

- Bruno Mealli and 26 other riders @ 1min 12sec

GC after Stage 6:

- Julio Jiménez: 27hr 33min 28sec

- Guido De Rosso @ 43sec

- Vito Taccone @ 53sec

- Gianni Motta @ 1mn 17sec

- Vittorio Adorni @ 1min 26sec

- Franco Balmamion @ 1min 30sec

- Italo Zilioli, Franco Bitossi @ 1min 58sec

- Felice Gimondi, Rolf Maurer @ 2min 55sec

Tuesday, May 24: Stage 7, Roma - Rocca di Cambio, 158 km

![]() Major ascents: Corno, Rocca di Cambio

Major ascents: Corno, Rocca di Cambio

- Rudi Altig: 4hr 50min 46sec

- Silvani Schiavon @ 3sec

- Gianni Motta @ 1mn 11sec

- Michele Dancelli @ 1min 13sec

- Felice Gimondi s.t.

- Italo Zilioli s.t.

- Jacques Anquetil s.t.

- Julio Jiménez s.t.

- Dino Zandegù s.t.

- Vittorio Adorni s.t.

GC after Stage 7:

- Julio Jiménez: 38hr 59min 5sec

- Guido De Rosso @ 43sec

- Vito Taccone @ 58sec

- Gianni Motta @ 1min 15sec

- Vittorio Adorni @ 1min 26sec

- Franco Balmamion @ 1min 30sec

- Italo Zilioli @ 1min 38sec

- Frano Bitossi @ 1min 56sec

- Silvano Schiavon @ 2min 51sec

- Felice Gimondi, Rolf Maurer @ 2min 55sec

Wednesday, May 25: Stage 8, Rocca di Cambio - Napoli, 238 km

- Marino Basso: 6hr 31min 3sec

- Bruno Mealli s.t.

- Jan Nolmans s.t.

- Renzo Baldan s.t.

- Jean Milesi s.t.

- Francesco Miele s.t.

- Adriano Passuello @ 35sec

- Jan Hugens @ 50sec

- Jean Graczyk @ 2min 35sec

- Raffaele Marcoli s.t.

GC after Stage 8:

- Julio Jiménez: 38hr 59min 5sec

- Guido De Rosso @ 43sec

- Vito Taccone @ 58sec

- Gianni Motta @ 1min 15sec

- Vittorio Adorni @ 1min 26sec

- Franco Balmamion @ 1min 30sec

- Italo Zilioli @ 1min 38sec

- Franco Bitossi @ 1min 58sec

- Silvano Schiavon @ 2min 51sec

- Felice Gimondi @ 2min 55sec

Thursday, May 26: Stage 9, Napoli - Campobasso, 210 km

- Vincent Denson: 6hr 44min 0sec

- Antonio Bailetti @ 44sec

- André Messelis @ 1min 40sec

- Gianni Motta @ 11min 2sec

- Franco Bitossi s.t.

- Vito Taccone s.t.

- Dino Zandegù s.t.

- Italo Zilioli s.t.

- Jacques Anquetil s.t.

- Rudi Altig s.t.

GC after Stage 9:

- Julio Jiménez: 45hr 10min 51sec

- Guido De Rosso @ 43sec

- Vito Taccone @ 58sec

- Gianni Motta @ 1min 15sec

- Vittorio Adorni @ 1min 26sec

- Franco Balmamion @ 1min 30sec

- Italo Zilioli @ 1min 38sec

- Franco Bitossi @ 1min 56sec

- Rudi Altig @ 3min 13sec

- Silvano Schiavon @ 3min 22sec

Friday, May 27: Stage 10, Campobasso - Giulianova, 221 km

- Dino Zandegù: 6hr 29min 18sec

- Marino Basso s.t.

- Vito Taccone s.t.

- Gianni Motta s.t.

- Franco Bitossi s.t.

- Mario Da Dalt s.t.

- Michele Dancelli s.t.

- Raffaele Marcoli s.t.

- Rudi Altig s.t.

- Flaviano Vicentini s.t.

GC after Stage 10:

- Julio Jiménez: 51hr 40min 9sec

- Guido De Rosso @ 43sec

- Vito Taccone @ 58sec

- Gianni Motta @ 1min 15sec

- Vittorio Adorni @ 1min 26sec

- Franco Balmamion @ 1min 30sec

- Italo Zilioli @ 1min 38sec

- Franco Bitossi @ 1min 56sec

- Rudi Altig @ 3min 13sec

- Felice Gimondi @ 3min 26sec

Saturday, May 28: Stage 11, Giulianova - Cesenatico, 229 km

- Rudi Altig: 6hr 20min 7sec

- Raffaele Marcoli @ 3sec

- Joseph Huysmans @ 8sec

- Arnaldo Pambianco s.t.

- Roberto Preziosi s.t.

- Sergio Destro s.t.

- Aldo Pifferi s.t.

- Bruno Mealli s.t.

- Ugo Colombo s.t.

- Flaviano Vicentini s.t.

GC after Stage 11:

- Julio Jiménez: 63hr 25min 29sec

- Guido De Rosso @ 43sec

- Vito Taccone @ 58sec

- Gianni Motta @ 1min 15sec

- Vittorio Adorni @ 1min 26sec

- Franco Balmamion @ 1min 30sec

- Italo Zilioli @ 1min 38sec

- Franco Bitossi @ 1min 56sec

- Rudi ALtig @ 2min 32sec

- Dino Zandegù @ 2min 41sec

Sunday, May 29: Stage 12, Cesenatico - Reggio Emilia, 206 km

- Dino Zandegù: 5hr 23min 23sec

- Michele Dancelli s.t.

- Mario Da Dalt s.t.

- Marino Basso s.t.

- Jan Nolmans s.t.

- Marino Vigna s.t.

- Bruno Fantinato s.t.

- Luciano Armani s.t.

- Roberto Ballini s.t.

- Joseph Huysmans s.t.

GC after Stage 12:

- Julio Jiménez: 63hr 25min 50sec

- Guido De Rosso @ 43sec

- Vito Taccone 2 58sec

- Gianni Motta @ 1min 15sec

- Vittorio Adorni @ 1min 26sec

- Franco Balmamion @ 1min 30sec

- Italo Zilioli @ 1min 38sec

- Franco Bitossi @ 1min 56sec

- Rudi Altig @ 2min 32sec

- Dino Zandegù @ 2min 41sec

Monday, May 30: Stage 13, Parma 46 km individual time trial

- Vittorio Adorni: 56min 46sec

- Jacques Anquetil @ 27sec

- Rudi Altig @ 56sec

- Gianni Motta @ 58sec

- Felice Gimondi @ 1min 26sec

- Rolf Maurer @ 1min 37sec

- Guido De Rosso @ 1min 54sec

- Italo Zilioli @ 2min 22sec

- Franco Balmamion @ 2min 47sec

- Jan Hugens @ 2min 52sec

GC after Stage 13:

- Vittorio Adorni: 64hr 24min 11sec

- Gianni Motta @ 47sec

- Guido De rosso @ 1min 13sec

- Rudi Altig @ 2min 2sec

- Italo Zilioli @ 2min 34sec

- Franco Balmamion @ 2min 51sec

- Julio Jiménez @ 3min 10sec

- Vito Taccone @ 3min 12sec

- Felice Gimondi @ 3min 26sec

- Jacques Anquetil @ 3min 35sec

Tuesday, May 31: Rest Day

Wednesday, June 1: Stage 14, Parma - Arona, 267 km

![]() Major ascent: Mottarone

Major ascent: Mottarone

- Franco Bitossi: 7hr 25min 31sec

- Gianni Motta @ 32sec

- Rudi Altig s.t.

- Rolf Maurer s.t.

- Felice Gimondi s.t.

- Vito Taccone s.t.

- Vittorio Adorni s.t.

- Italo Zilioli s.t.

- Jacques Anquetil s.t.

- Franco Balmamion s.t.

GC after Stage 14:

- Vittorio Adorni: 71hr 50min 14sec

- Gianni Motta @ 47sec

- Rudi Altig @ 2min 2sec

- Italo Zilioli @ 2min 34sec

- Franco Balmamion @ 2min 51sec

- Franco Bitossi, Guido De Rosso @ 3min 8sec

- Julio Jiménez @ 3min 10sec

- Vito Taccone @ 3min 12sec

- Felice Gimondi @ 3min 26sec

Thursday, June 2: Stage 15, Arona - Brescia, 196 km

![]() Major ascent: Brescia Maddalena

Major ascent: Brescia Maddalena

- Julio Jiménez: 4hr 51min 54sec

- Gianna Motta @ 30sec

- Italo Zilioli @ 31sec

- Rolf Maurer @ 33sec

- Jacques Anquetil s.t.

- Franco Bitossi @ 51sec

- Joseph Huysmans s.t.

- Franco Balmamion @ 53sec

- Felice Gimondi @ 1min 4sec

- Vito Taccone s.t.

GC after Stage 15:

- Gianni Motta: 78hr 43min 25sec

- Vittorio Adorni @ 7sec

- Italo Zilioli @ 48sec

- Julio Jiménez @ 1min 53sec

- Rudi Altig @ 2min 3sec

- Franco Balmamion @ 2min 27sec

- Franco Bitossi @ 2min 42sec

- Jacques Anquetil @ 2min 51sec

- Vito Taccone @ 2min 59sec

- Rolf Maurer @ 3min 5sec

Friday, June 3: Stage 16, Brescia - Bezzecca, 143km

![]() Major ascent: Bezzeca

Major ascent: Bezzeca

- Franco Bitossi: 4hr 0min 6sec

- Dino Zandegù s.t.

- Jacques Anquetil @ 2sec

- Vito Taccone s.t.

- Imerio Massignan s.t.

- Joseph Huysmans s.t.

- Gianni Motta s.t.

- Rolf Maurer s.t.

- Felice Gimondi s.t.

- Italo Zilioli s.t.

GC after Stage 16:

- Gianni Motta: 80hr 43min 33sec

- Vittorio Adorni @ 7sec

- Italo Zilioli @ 1min 48sec

- Julio Jiménez @ 1min 53sec

- Rudi Altig @ 2min 3sec

- Franco Balmamion @ 2min 27sec

- Franco Bitossi @ 2min 40sec

- Jacques Anquetil @ 2min 51sec

- Vito Taccone @ 2min 59sec

- Rolf Maurer @ 3min 5sec

Saturday, June 4: Stage 17, Ria del Garda - Levico Terme, 239 km

![]() Major ascent: Vetriolo

Major ascent: Vetriolo

- Gianni Motta: 7hr 1min 28sec

- Julio Jiménez @ 3sec

- Franco Bitossi @ 1min 17sec

- Rudi Altig @ 1min 36sec

- Felice Gimondi @ 1min 37sec

- Jacques Anquetil s.t.

- Franco Balmamion s.t.

- Vito Taccone @ 1min 50sec

- Italo Zilioli @ 1min 56sec

- Franco Bodrero @ 2min 23sec

GC after Stage 17:

- Gianni Motta: 87hr 45min 1sec

- Julio Jiménez @ 1min 56sec

- Rudi Altig @ 3min 39sec

- Italo Zilioli @ 3min 44sec

- Franco Bitossi @ 3min 57sec

- Franco Balmamion @ 4min 4sec

- Jacques Anquetil @ 4min 28sec

- Vito Taccone @ 4min 49sec

- Felice Gimondi @ 4min 50sec

- Vittorio Adorni @ 5min 5sec

Sunday, June 5: Stage 18, Levico Terme - Bolzano, 137 km

![]() Major ascent: Palade

Major ascent: Palade

- Michele Dancelli: 3hr 27min 36sec

- Adriano Durante s.t.

- Jan Nolmans s.t.

- Jean Stablinski s.t.

- Bruno Centomo s.t.

- Francesco Miele s.t.

- Giuseppe Fezzardi s.t.

- Pierre Everaert s.t.

- Antoon Houbrechts @ 2min 29sec

- Renzo Baldan s.t.

GC after Stage 18:

- Gianni Motta: 91hr 17min 1sec

- Julio Jiménez @ 1min 56sec

- Rudi Altig @ 3min 39sec

- Italo Zilioli @ 3min 44sec

- Franco Bitossi @ 3min 54sec

- Franco Balmamion @ 4min 4sec

- Jacques Anquetil @ 4min 28sec

- Vito Taccone @ 4min 46sec

- Felice Gimondi @ 4min 50sec

- Vittorio Adorni @ 5min 6sec

Monday, June 6: Stage 19, Bolzano - Moena, 100 km

![]() Major ascents: Lavaze, Costalunga

Major ascents: Lavaze, Costalunga

- Gianni Motta: 3hr 13min 7sec

- Jacques Anquetil @ 1sec

- Italo Zilioli @ 2sec

- Joseph Huysmans @ 13sec

- Graziano Battistini @ 24sec

- Vito Taccone @ 2min 10sec

- Felice Gimondi @ 2min 12sec

- Flaviano Vicentini @ 2min 13sec

- Franco Balmamion @ 2min 42sec

- Vittorio Adorni @ 2min 44sec

GC after Stage 19:

- Gianni Motta: 94hr 30min 6sec

- Italo Zilioli @ 3min 46sec

- Jacques Anquetil @ 4min 29sec

- Julio Jiménez @ 5min 33sec

- Franco Balmamion @ 6min 46sec

- Vito Taccone @ 6min 56sec

- Felice Gimondi @ 7min 2sec

- Vittorio Adorni @ 7min 49sec

- Franco Bitossi @ 9min 22sec

- Rudi Altig @ 13min 49sec

Tuesday, June 7: Stage 20, Moena - Belluno, 215 km

![]() Major ascents: Pordoi, Falzarego, Tre Croci, Cibiana, Duran

Major ascents: Pordoi, Falzarego, Tre Croci, Cibiana, Duran

- Felice Gimondi: 6hr 53min 15sec

- Vittorio Adorni @ 26sec

- Joseph Huysmans s.t.

- Jacques Anquetil s.t.

- Gianni Motta s.t.

- Franco Bitossi s.t.

- Italo Zilioli s.t.

- Franco Balmamion s.t.

- Julio Jiménez s.t.

- Rolf Maurer @ 4min 10sec

GC after Stage 20:

- Gianni Motta: 100hr 23min 49sec

- Italo Zilioli @ 3min 46sec

- Jacques Anquetil @ 4min 29sec

- Julio Jiménez @ 5min 33sec

- Felice Gimondi @ 6min 36sec

- Franco Balmamion @ 6min 46sec

- Vittorio Adorni @ 7min 49sec

- Franco Bitossi @ 9min 22sec

- Vito Taccone @ 11min 40sec

- Rolf maurer @ 20min 17sec

Wednesday, June 8: Stage 21, Belluno - Vittorio Veneto, 181 km

![]() Major ascents: San Boldo, Bosco di Cansiglio

Major ascents: San Boldo, Bosco di Cansiglio

- Pietro Scandelli: 4hr 44min 15sec

- Lucillo Lievore @ 15min 18sec

- Vendramino Bariviera @ 16min 26sec

- Pietro Partesotti @ 16min 31sec

- Roberto Ballini @ 16min 33sec

- Gianni Motta s.t.

- Joseph Huysmans s.t.

- Egidio Cornale s.t.

- Vito Taccone s.t.

- Franco Bitossi s.t.

GC after Stage 21:

- Gianni Motta: 106hr 24min 38sec

- Italo Zilioli @ 3min 57sec

- Jacques Anquetil @ 4min 40sec

- Julio Jiménez @ 5min 44sec

- Felice Gimondi @ 6min 47sec

- Franco Balmamion @ 7min 27sec

- Vittorio Adorni @ 8min 0sec

- Franco Bitossi @ 9min 24sec

- Vito Taccone @ 11min 42sec

- Rolf Maurer @ 20min 28sec

Thursday, June 9: 22nd and final stage, Vittorio Veneto - Trieste, 172 km

- Vendramino Bariviera: 4hr 45min 8sec

- Joseph Huysmans s.t.

- Antonio Bailetti s.t.

- Flaviano Vicentini s.t.

- Marino Basso s.t.

- Giuseppe Fezzardi s.t.

- Giampiero Macchi s.t.

- Rudi Altig @ 1min 5sec

- Michele Dancelli s.t.

- Dino Zandegù s.t.

The Story of the 1966 Giro d'Italia

This excerpt is from "The Story of the Giro d'Italia", Volume 1. If you enjoy it we hope you will consider purchasing the book, either print or electronic. The Amazon link here will make either purchase easy.

This is a complicated one. I suspect in the end they all are and it’s only our ignorance of what is going on among the professionals as they race and scheme to find the desired balance between maximum income and race wins that keeps us from fully appreciating the complexity of any given competition.

To grasp the politics that permeate this race it’s necessary to give a little background. Ford France now sponsored Anquetil’s team, which included the gifted Spanish climber Julio Jiménez. Ford had set up regional semi-autonomous companies to sell its cars in Europe. Ford France had its own budget and was independent from Ford Italy. In the Riviera where France borders Italy, Ford Italy lured buyers over the border to buy their lower-priced cars, setting up an ongoing feud between the two firms.

Late in the 1966 Giro, though I have never been able to find out exactly when, Anquetil told his team to deaden their efforts to win the Giro. It later turned out the manager of Ford France had asked the boss of Ford Italy to help defray the team’s expenses since Ford Italy was reaping such a wonderful windfall of publicity from Anquetil’s Giro entry, paid for by Ford France. Ford Italy refused to help, probably thinking that a free ride was in the offing. It is thought that the Ford France manager told Anquetil to throw the race rather than continue giving free publicity to Ford Italy. Later in the year Anquetil domestique Vin Denson said that Anquetil gave him a bonus big enough to buy a car, saying that the money was from the Giro, but refused to elaborate. Was this payment from Ford France to make up for the race prizes the powerful team didn’t win and/or for lost pride? Or did Anquetil get money from the other teams to pay him for what he had already been told to do? We’ll never know. We’ll also never know when Anquetil decided to race for money rather than for victory, but it may well have been just after the first stage.

Against Anquetil, who was now trying for his third Giro victory, were Adorni and Felice Gimondi, who had proved to be a magnificent talent. In the spring Gimondi won Paris–Roubaix and that fall he would go on to take the Tour of Lombardy. He could race anywhere and win. The plan was for Gimondi to rest after the spring Classics and then go for a second Tour win. But Torriani badly wanted the young hero and was able to talk Pezzi into entering Gimondi in the Giro.

Also on the start line were Zilioli, Bitossi, Balmamion and Gianni Motta.

The first stage was crucial to the entire race. The Giro again had a foreign departure, this time from Monte Carlo in Monaco where Princess Grace presided over the race’s commencement celebrating Monte Carlo’s hundredth anniversary.

The day’s primary obstacle on the way to the first finish line at Diano Marina on the Italian Riviera was the Colle San Bartolomeo. Midway up the climb, about three kilometers from the top, Anquetil still had the front group under control when a tifoso, who wanted to give Anquetil a glass bottle of water, tripped and fell, breaking the bottle just under Anquetil’s tires. Both tires flatted. Luckily Anquetil had a gregario with him. Anquetil switched wheels with his teammate and began what Zilioli described as a “crazy chase”. At this point the front group was unaware of Anquetil’s misfortune.

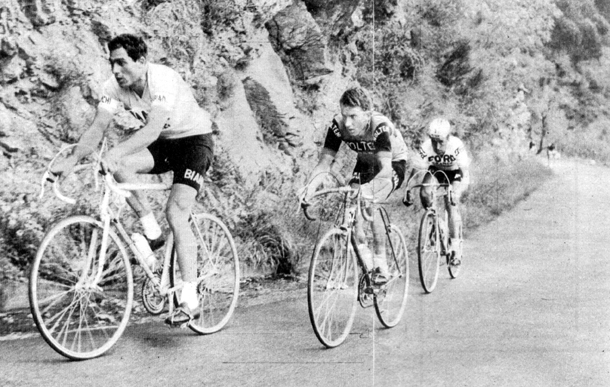

Dino Zandegù, Gianni Motta and Julio Jiménez on the San Bartolomeo

A break of 22 riders with Jiménez, Gimondi, Bitossi, Zilioli, Motta, Balmamion, De Rosso and Taccone went over the San Bartolomeo about 100 meters in front of Anquetil. Zilioli was full of admiration for Anquetil’s chase, calling it a “great performance”, saying that the Frenchman passed many riders and recovered 40-45 seconds in three kilometers. But he could not catch the leaders.

The leaders descended at top speed arriving at the bottom fifteen to twenty seconds ahead of Anquetil, who Zilioli said wasn’t that fast on descents. At this point the front group realized that Anquetil was chasing and, almost unable to believe their good fortune, decided to pound the big gears for all they were worth. Anquetil gave desperate chase for ten kilometers, staying just fifteen or so seconds behind his quarry, but he couldn’t close the gap. Finally realizing that the game was up, that there was too much determined and organized horsepower up the road, Anquetil stopped his pursuit, finishing a little more than three minutes after Vito Taccone won the stage.

At this point Anquetil believed he could not win the 1966 Giro d’Italia. Zilioli said that apart from a few occasions, during this Giro Anquetil did not show the superiority that everyone knew he had. But, he did have a powerful teammate in Jiménez in the break who was now sitting well placed in the General Classification.

Anquetil biographer Paul Howard relates that after the first stage Anquetil told Géminiani that, although he felt he could not win the Giro, he could decide who would win. Specifically, he didn’t want Gimondi to win. Gimondi was growing ever more popular and Anquetil wanted no threat to his status as top dog. During the 1950s and 1960s a racer often made the bulk of his money in post-Tour criteriums and Anquetil knew that his place as the pre-eminent racer in the world meant a fortune in race start and appearance fees. He obsessed about his value to race promoters, always doing everything in his power to make sure that he was the premier rider who could command top price.

Anquetil wasn’t doing anything new when he raced to prevent Gimondi from gaining a Giro: that would just make Gimondi more popular, and threaten Anquetil’s future income. In the past when victory was beyond him, he had ridden to prevent a rival’s winning. At the mysterious point in this Giro when he decided that his team should not race for the General Classification win, he chose to race for Gianni Motta.

The next day was a short 60-kilometer stage ending at the 1,300-meter high city of Monesi in the Ligurian Alps. Jiménez galloped away, putting one and a half minutes between himself and the pack. The Spanish Ford France rider was now in pink. Highlighting the Ford Italy/France feud, during the awards ceremonies the Ford France riders wore Cynar hats and jumpsuits with just small Ford logos.

The General Classification was now thus:

1. Julio Jiménez

2. Gianni Motta @ 1 minute 23 seconds

3. (tie) Felice Gimondi and Rolf Maurer @ 1 minute 25 seconds

5. Vittorio Adorni @ 1 minute 32 seconds

6. Franco Balmamion @ 1 minute 36 seconds

The third stage was an insanely fast wind-aided rush to Genoa. Near the end of the leg the pack entered a dark tunnel where Gimondi flatted. In the poor light his slow wheel change cost him a minute and a half and a good shot at winning.

As the race moved south, Jiménez maintained his leadership. In stage five De Rosso was able to get into a break that moved him into second place at 43 seconds, but Motta stayed close to the Spaniard, in fourth place, 1 minute 17 seconds back. That relationship remained unchanged throughout the next eight stages. By stage thirteen, the scene of a 46-kilometer individual time trial, the Giro had made it all the way down to Naples and had headed north up to Parma

During the final kilometers of stage eight, finishing in Naples, Anquetil gregario Vin Denson helped chase down a break with several famous Italians, including Marino Basso and Bruno Mealli. As the riders roared through the narrow streets with their overhanging balconies, the Neapolitans threw garbage down on the foreign riders. Denson said he stank horribly after the stage. Throughout the race Denson said he had to ride next to Jiménez to protect him from the sometimes too-zealous tifosi.

Jiménez was like nearly all gifted pure climbers in that he was a poor time-trialist, and in stage thirteen he lost 4 minutes 36 seconds. His time in pink was over.

The stage results:

1. Vittorio Adorni

2. Jacques Anquetil @ 27 seconds

3. Rudi Altig @ 56 seconds

4. Gianni Motta @ 58 seconds

5. Felice Gimondi @ 1 minute 26 seconds

This made for the following General Classification:

1. Vittorio Adorni

2. Gianni Motta @ 47 seconds

3. Guido De Rosso @ 1 minute 13 seconds

4. Rudi Altig @ 2 minutes 2 seconds

5. Italo Zilioli @ 2 minutes 34 seconds

10. Jacques Anquetil @ 3 minutes 35 seconds

Adorni was again the maglia rosa and had the privilege of owning it during the rest day. He kept his lead the next stage when the race rode north to Lombardy but ran into trouble in stage fifteen, which went over the heavy, difficult roads of northern Lombardy. The peloton blew up into almost as many pieces as there were riders. Jiménez was first into Bréscia, followed at about thirty seconds by Motta, Zilioli, Maurer and Anquetil, while Adorni and De Rosso lost a minute and a half. Gianni Motta took the lead by a slim 7 seconds over Adorni.

Since he turned pro in 1964 at the age of 21, Motta’s career had been brilliant. In his first professional year he won not only the Coppa Bernocchi, he also took the Tour of Lombardy. The next year he was third in the Tour de France.

Motta continued to ride well, winning the seventeenth stage to Levico Terme in the Dolomites. Jiménez was first over the dirt roads of the Vetriolo climb after a hard climbing duel with Motta, but Motta dug deep and managed to take the stage win three seconds ahead of the Spaniard. It turned out that Motta could be a scattista, a fine talent when battling Jiménez. Gimondi, Anquetil and Balmamion came in a minute and a half later.

That left the General Classification thus:

1. Gianni Motta

2. Julio Jiménez @ 1 minute 56 seconds

3. Rudi Altig @ 3 minutes 39 seconds

4. Italo Zilioli @ 3 minutes 44 seconds

5. Franco Bitossi @ 3 minutes 57 seconds

6. Franco Balmamion @ 4 minutes 4 seconds

7. Jacques Anquetil @ 4 minutes 28 seconds

Motta won again, this time the nineteenth stage with its Lavaze and Costalunga ascents. Anquetil and Zilioli finished right with him but Jiménez lost more than three minutes, moving Zilioli to second and Anquetil to third place.

It almost feels as if a truce had settled over the race at this point. The twentieth stage was massive: 215 kilometers going over the Pordoi, Falzarego, Tre Croci, Cibiana and Duran passes. Yet with the exception of Gimondi’s finishing 26 seconds ahead of the first group, the big guys Adorni, Anquetil, Motta, Bitossi, Zilioli, Balmamion and Jimenez all finished together.

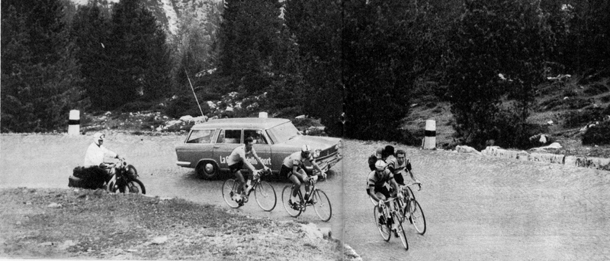

Schiavon, Zilioli, Bitossi, Partesotti and Motta on the Pordoi.

Certainly Ford France was done contesting the race. Vin Denson told of a mountain stage where Anquetil told his team not to react to a Motta attack. Anquetil pretended to get a puncture and then made a drama out of getting a new wheel with gears too high for the mountain, thus allowing him to let Motta fly away without looking bad.

With just two stages left to go Motta had won the 1966 Giro, beating a stellar field under odd circumstances. We asked Zilioli about the rumors of payments to Anquetil. His response was firm. He said while these things happen in races he had no knowledge of any such agreement in the 1966 Giro and he and his team had no interest in buying Anquetil, especially for second place. “I had already been second in ’64 and ’65…”

And he was second again in ’66.

Since 1953, the Tour had been awarding a green jersey based on points, to give the sprinters something to race for besides stage wins. While 1967 was the first year for the Giro to award a jersey to its top points winner, the prize was created in 1966, which Motta won. Motta’s victory was nearly complete. He won the General Classification and points but had to be satisfied with only third in the climbers’ category. While it was an outstanding victory, the good God had not sent yet Italy another Coppi. Motta would be plagued with physical problems and bad advice from a medical charlatan that kept him from accruing the imposing win list that his talent justified.

Gianni Motta in the maglia rosa

Final 1966 Giro d’Italia General Classification:

1. Gianni Motta (Molteni) 111 hours 10 minutes 48 seconds

2. Italo Zilioli (Sanson) @ 3 minutes 57 seconds

3. Jacques Anquetil (Ford France) @ 4 minutes 40 seconds

4. Julio Jiménez (Ford France) @ 5 minutes 44 seconds

5. Felice Gimondi (Salvarani) @ 6 minutes 47 seconds

Climbers’ Competition:

1. Franco Bitossi (Filotex): 490 points

2. Julio Jiménez (Ford France): 320

3. Gianni Motta (Molteni): 160

Points Competition:

1. Gianni Motta (Molteni): 228 points

2. Rudi Altig (Molteni): 162

3. Vito Taccone (Vittadello): 152

For the first time in the history of the Giro d’Italia, 86-year old Eberardo Pavesi did not participate in some capacity, either as a racer or team director. As a rider he had been a member of the winning Atala team in the 1912 Giro. He also won the 1905 Tour of Lombardy and the 1907 Milan–San Remo and is the first Italian to finish the Tour de France, placing sixth in 1907. After he retired from racing in 1919 he went on to a long career as a team director for Legnano, managing such greats as Binda, Bartali and Coppi. His nickname was l’avvocato (the lawyer) because of his ability to use the racing rulebook to his and his teams’ advantage.

Later that year Motta generously repaid teammate Molteni teammate Rudi Altig (who had won the Vuelta in 1962) for his help in the Giro by crossing national team lines and helping the German win the World Road Championship.Italian video of Stage 17 finishing in Levico Terme

.