1974 Giro d'Italia

57th edition: May 16 - June 9

Results, stages with running GC, startlist with backnumbers, map, photos and history

1973 Giro | 1975 Giro | Giro d'Italia Database | 1974 Giro Quick Facts | 1974 Giro d'Italia Final GC | Race Summary | Stage results with running GC | Startlist with Backnumbers | The Story of the 1974 Giro d'Italia

Map of the 1974 Giro d'Italia

4,001 km raced at an average speed of 35.37 km/hr

140 enrolled (137 starters) and 96 classified finishers

José-Manuel Fuente took the lead in stage three and looked to be strong enough to withstand Eddy Merckx's assult, but in stage 14 Fuente famously forgot to eat, ran completely out of energy and lost more than 10 minutes.

From there, Merckx, despite a ferocious fight from Baronchelli, was able to remain the leader (by only 12 seconds) all the way to Milan.

This was Merckx's fifth Giro win, tying him with Binda and Coppi.

Les Woodland's book Cycling Heroes: The Golden Years is available as an audiobook here

1974 Giro d'Italia Complete Final General Classificaton:

Eddy Merckx (Molteni): 113hr 8min 13sec

Eddy Merckx (Molteni): 113hr 8min 13sec- Giambattista Baronchelli (SCIC) @ 12sec

- Felice Gimondi (Bianchi) @ 33sec

- Constantino Conti (Zonca) @ 2min 14sec

- José-Manuel Fuente (KAS) @ 3min 22sec

- Giovanni Battaglin (Jolly Ceramica) @ 4min 22sec

- Francesco Moser (Filotex) @ 6min 17sec

- Vicente López-Carril (KAS) @ 10min 28sec

- Franco Bitossi (SCIC) @ 16min 5sec

- Gösta Pettersson (Magniflex) @ 17min 8sec

- Roger de Vlaeminck (Brooklyn) @ 18min 28sec

- Wladimiro Panizza (Brooklyn) @ 20min 48sec

- Antoon Houbrechts (Bianchi) @ 20min 55sec

- José-Luis Uribezubia (KAS) @ 22min 12sec

- Walter Riccomi (Sammontana) @ 23min 29sec

- Santiago Lazcano (KAS) @ 24min 29sec

- Francisco Galdós (KAS) @ 25min 54sec

- Martin "Cochise" Rodriguez (Bianchi) @ 26min 36sec

- Giuseppe Perletto (Sammontana) @ 28min 1sec

- Roberto Poggiali (Filotex) @ 30min 33sec

- Giovanni Cavalcanti (Bianchi) @ 41min 20sec

- Giacinto Santambrogio (Bianchi) @ 41min 35sec

- Primo Mori (Sammontana) @ 46min 35sec

- Gianni Motta (Magniflex) @ 47min 33sec

- Josef Fuchs (Filotex) s.t.

- Luciano Conati (SCIC) @ 53min 21sec

- Luis Zubero (KAS) @ 1hr 3min 8sec

- José-Antonio Ginzalez-Linares (KAS) @ 1hr 3min 27sec

- Donato Giuliani (Filotex) @ 1hr 5min 40sec

- Silvano Schiavon (Magniflex) @ 1hr 5min 52sec

- Renato Laghi (SCIC) @ 1hr 6min 30sec

- Louis Pfenninger (Zonca) @ 1hr 13min 48sec

- Gonzalo Aja (KAS) @ 1hr 17min 13sec

- Edward Janssens (Molteni) @ 1hr 19min 8sec

- Claudio Bortolotto (Filcas) @ 1hr 19min 38sec

- Johan de Muynck (Brooklyn) @ 1hr 21min 32sec

- Jos de Schoenmaecker (Molteni) @ 1hr 21min 36sec

- Adrian Pella (Zonca) @ 1hr 22min 3sec

- Ugo Colombo (Filotex) @ 1hr 22min 7sec

- Johan Ruch (Rokado) @ 1hr 26min 36sec

- Raphael Nino (Jolly Ceramica) @ 1hr 28min 58sec

- Antonio Martos (KAS) @ 1hr 29min 56sec

- Fabrizio Fabbri (Sammontana) @ 1hr 35min 52sec

- Mario Lanzafame (Dreherforte) @ 1hr 36min 54sec

- Joseph Huysmans (Molteni) @ 1hr 38min 7sec

- Enrico Paolini (SCIC) @ 1hr 38min 41sec

- Giancarlo Bellini (Brooklyn) @ 1hr 38min 56sec

- Emauele Bergamo (Filotex) @ 1hr 40min 47sec

- Simone Fraccaro (Filcas) @ 1hr 43min 0sec

- Ludo Delcroix (Molteni) @ 1hr 44min 6sec

- Victor van Schil (Molteni) @ 1hr 44min 54sec

- Joseph Bruyère (Molteni) @ 1hr 46min 17sec

- Efrem Dall'Anese (Filcas) @ 1hr 47min 34sec

- Knut Knudsen (Jolly Ceramica) @ 1hr 48min 28sec

- Enrico Guardrini (Zonca) @ 1hr 49min 53sec

- Roland Salm (Zonca) @ 1hr 50min 33sec

- Sigfrido Fontanelli (Sammontana) @ 1hr 53min 27sec

- Attilio Rota (Brooklyn) @ 1hr 56min 26sec

- José Grande (KAS) @ 1hr 56min 54sec

- Alessio Peccolo (Filcas) @ 2hr 1min 11sec

- Eric Spahn (Zonca) @ 2hr 6min 27sec

- Arnaldo Caversasi (Filotex) @ 2hr 9min 6sec

- Celestino Vercelli (SCIC) @ 2hr 11min 21sec

- Karel Rottiers (Molteni) @ 2hr 12min 33sec

- Roberto Sorlini (Filotex) @ 2hr 13min 33sec

- Wilmo Francioni (Sammontana) @ 2hr 14min 11sec

- Karl-Heinz Küster (Rokado) @ 2hr 15min 25sec

- Lino Venterato (Filcas) @ 2hr 15min 38sec

- Albert van Vlierberghe (Molteni) @ 2hr 16min 49sec

- Mauro Simonetti (Sammontana) @ 2hr 19min 22sec

- Alessio Antonini (Jolly Ceramica) @ 2hr 21min 23sec

- Alfred Gaida (Rokado) @ 2hr 25min 11sec

- Bruno Zanoni (SCIC) @ 2hr 28min 34sec

- Frans Mintjens (Molteni) @ 2hr 28min 43sec

- Julien van Lint (Brooklyn) @ 2hr 31min 26sec

- Pietro Campagnari (Dreherforte) @ 2hr 32min 5sec

- Sandro Quintarelli (Magniflex) @ 2hr 33min 46sec

- Gino Fochesato (Dreherforte) @ 2hr 35min 39sec

- Marcello Osler (Sammontana) @ 2hr 38min 33sec

- Giacomo Bazzan (Jolly Ceramica) @ 2hr 40min 56sec

- Gianfranco Foresti (Bianchi) @ 2hr 41min 40sec

- Luciano Rossignoli (Filcas) @ 2hr 43min 40sec

- Giorgio Favaro (Zonca) @ 2hr 45min 46sec

- Gaetano Baronchelli (SCIC) @ 2hr 47min 27sec

- Marino Basso (Bianchi) @ 2hr 49min 58sec

- Roger Gilson (Rokado) @ 2hr 51min 1sec

- Herman van der Slagmolen (Brooklyn) @ 2hr 53min 16sec

- Albert Zweifel (Furzi) @ 2hr 53min 23sec

- Adriano Passuello (Brooklyn) @ 2hr 53min 55sec

- Attilio Benfatto (Filcas) @ 2hr 57min 52sec

- Piero Spinelli (SCIC) @ 2hr 58min 17sec

- Günther Haritz (Rokado) @ 2hr 59min 0sec

- Giancarlo Tartoni (Furzi) @ 2hr 59min 49sec

- Pietro Guerra (Bianchi) @ 3hr 1min 22sec

- Daniele Mazziero (Magniflex) @ 3hr 2min 54sec

- Ercole Gualazzini (Brooklyn) @ 3hr 14min 23sec

Points Classification (at the time a purple jersey was awarded):

Roger de Vlaeminck (Brooklyn): 265 points

Roger de Vlaeminck (Brooklyn): 265 points- Franco Bitossi (SCIC): 209

- José-Manuel Fuente (KAS): 171

- Eddy Merckx (Molteni): 161

- Francesco Moser (Filotex): 152

Climbers' Competition: (1974 was the first year a Green Jersey was awarded to KOM leader)

José-Manuel Fuente (KAS): 510 points

José-Manuel Fuente (KAS): 510 points- Eddy Merckx (Molteni): 330

- Santiago Lazcano (KAS): 230

- Giuseppe Perletto (Sammontana): 160

- Giambattista Baronchelli (SCIC): 120

Team Classification

- KAS

- Brooklyn

- SCIC

Race Summary: Merckx took the Pink Jersey on the May 31 stage

Date |

Stage |

Dist. km |

Speed |

Winner |

2nd |

3rd |

| May 16 | Vaticano-Formia | 164 | 38.407 | Reybrouck | De Vlaeminck | Basso |

| May 17 | Formia-Pompei | 121 | 42.911 | Sercu | Santambrogio | De Vlaeminck |

| May 18 | Pompei-Sorrento | 137 | 34.770 | Fuente | Moser | Battaglin |

| May 19 | Rest Day | |||||

| May 20 | Sorrento-Sapri | 208 | 34.176 | De Vlaeminck | Vicino | Gavazzi |

| May 21 | Sapri-Taranto | 215 | 35.348 | Gavazzi | Gualazzini | De Vlaeminck |

| May 22 | Taranto-Foggia | 206 | 34.620 | Bitossi | Rottiers | Avogadri |

| May 23 | Foggia-Chieti | 257 | 35.536 | Colombo | De Vlaeminck | Bergamo, M. |

| May 24 | Chieti-Macerata | 150 | 34.536 | Bitossi | Rodriguez | Botolotto |

| May 25 | Marcerata-Carpegna | 191 | 31.293 | Fuente | Merckx | Paolini |

| May 26 | Carpegna-Modena | 205 | 42.510 | Sercu | Basso | De Vlaeminck |

| May 27 | Modena-Il Ciocco

Il Ciocco-F.dei Marmi |

153

62 |

32.727

35.987 |

Fuente

Sercu |

Merckx

D.Vlaeminck |

Conti

Osler |

| May 28 | Forte dei Marmi (ITT) | 40 | 48.468 | Merckx | Moser | Pettersson |

| May 29 | Rest Day | |||||

| May 30 | Forte dei Marmi-Pietra Ligure | 231 | 36.156 | Paolini | Gavazzi | De Vlaeminck |

| May 31 | P. Ligure-San Remo | 190 | 35.406 | Perletto | Panizza | Barochelli |

| June 1 | San Remo-Valenza | 206 | 35.123 | Gualzzini | Zanoni | Simonetti |

| June 2 | Valenza-Mendrisio | 158 | 36.322 | Fuente | Gimondi | Perletto |

| June 3 | Como-Iseo | 125 | 32.243 | Lazcano | Fuente | De Vlaeminck |

| June 4 | Iseo-Selle Valsugana | 190 | 32.971 | Bitossi | Merckx | Gimondi |

| June 5 | Borgo Valsugana-Podenone | 146 | 35.806 | Paolini | Knudsen | Basso |

| June 6 | Pordenone-Tre Cime di Lavaredo | 163 | 28.689 | Fuente | Baronchelli, G.B. | Conti |

| June 7 | Misurina-Bassana del Grappa | 194 | 31.618 | Merckx | Moser | Gimondi |

| June 8 | Bassano del Grappa-Milano | 257 | 39.407 | Basso | De Vlaeminck | Bitossi |

Stage results with running GC:

Thursday, May 16: Stage 1, Vatican City- Formia, 164 km

- Wilfried Reybrouck: 4hr 16min 12sec

- Roger de Vlaeminck s.t.

- Marino Basso s.t.

- Enrico Paolini s.t.

- Patrick Sercu s.t.

- Alfred Gaida s.t.

- Alessio Antonini s.t.

- Hennie Kuiper s.t.

- Franco Bitossi s.t.

- Pierino Gavazzi s.t.

Friday, May 17: Stage 2, Formia - Pompei, 121 km

- Patrick Sercu: 2hr 49min 11sec

- Giacinto Santambrogio s.t.

- Roger de Vlaeminck s.t.

- Sigfrido Fontanelli s.t.

- Marino Basso s.t.

- Franco Bitossi s.t.

- Gianni Motta s.t.

- Alessio Antonini s.t.

- Joseph Huysmans s.t.

- Pierino Gavazzi s.t.

GC after Stage 2:

- Wilfried Reybrouck: 7hr 5min 23sec

- Roger de Vlaeminck s.t.

- Marino Basso s.t.

- Enrico Paolini s.t.

- Patrick Sercu s.t.

- Alfred Gaida s.t.

- Alessio Antonini s.t.

- Hennie Kuiper s.t.

- Franco Bitossi s.t.

- Pierino Gavazzi s.t.

Saturday, May 18: Stage 3, Pompei - Sorrento, 137 km

![]() Major ascents: Agerola, Faito

Major ascents: Agerola, Faito

- José-Manuel Fuente: 3hr 56min 24sec

- Francesco Moser @ 33sec

- Giovanni Battaglin s.t.

- Italo Zilioli s.t.

- Felice Gimondi s.t.

- Constantino Conti s.t.

- José-Luis Uribezubia s.t.

- Santiago Lazcano s.t.

- Ole Ritter @ 42sec

- Vicente López-Carril s.t.

GC after Stage 3:

- José-Manuel Fuente: 11hr 1min 47sec

- Francesco Moser, Santiago Lazcano, Felice Gimondi, Italo Zilioli, José-Luis Uribezubia, Giovanni Battaglin, Constantino Conti @ 33sec

Sunday, May 19: Rest Day

Monday, May 20: Stage 4, Sorrento - Sapri, 208 km

- Roger de Vlaeminck: 5hr 58min 36sec

- Bruno Vicino s.t.

- Pierino Gavazzi s.t.

- Johan Ruch s.t.

- Patrick Sercu s.t.

- Alessio Antonini s.t

- Karel Rottiers s.t.

- Marino Basso s.t.

- Franco Bitossi s.t.

- Gianfranco Foresti s.t.

GC after Stage 4:

- José-Manuel Fuente: 17hr 0min 23sec

- Francesco Moser, Santiago Lazcano, Felice Gimondi, Italo Zilioli, José-Luis Uribezubia, Giovanni Battaglin, Constantino Conti @ 33sec

Tuesday, May 21: Stage 5, Sapri - Taranto, 215 km

- Pierino Gavazzi: 6hr 4min 57sec

- Ercole Gualazzini s.t.

- Roger de Vlaeminck s.t.

- Bruno Vicino s.t.

- Walter Riccomi s.t.

- Franco Bitossi s.t.

- Francesco Moser s.t.

- Marino Basso s.t.

- Alessio Antonini s.t.

- Gianfranco Foresti s.t.

GC after Stage 5:

- José-Manuel Fuente: 23hr 5min 20sec

- Francesco Moser, Felice Gimondi, Italo Zilioli, José-Luis Uribezubia, Giovanni Battaglin, Constantino Conti @ 33sec

- Roger de Vlaeminck, Franco Bitossi, Walter Riccomi, Eddy Merckx, Vicente López-Carril, Ole Ritter, Giambattista Baronchelli @ 42sec

Wednesday, May 22: Stage 6, Taranto - Foggia, 206 km

- Franco Bitossi: 5hr 57min 0sec

- Karel Rottiers @ 2sec

- Walter Avogadri s.t.

- Roger de Vlaeminck s.t.

- Pierino Gavazzi s.t.

- Patrick Sercu s.t.

- Ercole Gualazzini s.t.

- Walter Riccomi s.t.

- Roland Salm s.t.

- Hennie Kuiper s.t.

GC after Stage 6:

- José-Manuel Fuente: 29hr 2min 22sec

- Francesco Moser, Felice Gimondi, Italo Zilioli, José-Luis Uribezubia, Giovanni Battaglin, Constantino Conti @ 33sec

- Roger de Vlaeminck, Franco Bitossi, Walter Riccomi, Eddy Merckx, Vicente López-Carril, Ole Ritter, Giambattista Baronchelli @ 42sec

Thursday, May 23: Stage 7, Foggia - Chieti, 257 km

- Ugo Colombo: 7hr 26min 28sec

- Roger de Vlaeminck @ 44sec

- Marcello Bergamo s.t.

- Eddy Merckx s.t.

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 46sec

- Franco Bitossi s.t.

- Felice Gimondi s.t.

- Ole Ritter @ 47sec

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 48sec

- Italo Zilioli s.t.

GC after Stage 7:

- José-Manuel Fuente: 36hr 29min 41sec

- Felice Gimondi @ 28sec

- Italo Zilioli, Giovanni Battaglin @ 30se

- Francesco Moser @ 32sec

- José-Luis Uribezubia @ 34sec

- Roger de Vlaeminck, Franco Bitossi, Eddy Merckx, Constantino Conti @ 35sec

Friday, May 24: Stage 8, Chieti - Macerata, 150 km

- Franco Bitossi: 4hr 19min 8sec

- Martin "Cochise" Rodriguez s.t.

- Claudio Bartolotto s.t.

- Francesco Moser s.t.

- Victor van Schil s.t.

- Sigfrido Fontanelli s.t.

- Pierino Gavazzi s.t.

- Guerrino Tosello s.t.

- Louis Pfenninger s.t.

- Wilmo Francioni s.t.

GC after Stage 8:

- José-Manuel Fuente: 40hr 48min 49sec

- Felice Gimondi @ 28sec

- Italo Zilioli, Giovanni Battaglin @ 30sec

- Francesco Moser @ 32sec

- José-Luis Uribezubia @ 34sec

- Roger de Vlaeminck, Francpo Bitossi, Eddy Merckx, Constantino Conti @ 35sec

Saturday, May 25: Stage 9, Macerate - Monte Carpegna, 191 km

![]() Major ascent: Monte Carpegna

Major ascent: Monte Carpegna

- José-Manuel Fuente: 6hr 6min 11sec

- Eddy Merckx @ 1min 5sec

- Enrico Paolini @ 1min 44sec

- Roger De Vlaeminck s.t.

- Marcello Bergamo s.t.

- Felice Gimondi s.t.

- Roberto Poggiali s.t.

- Franco Bitossi s.t.

- Hennie Kuiper s.t.

- Wladimiro Panizza s.t.

GC after Stage 9:

- José Manuel Fuente: 46hr 55min 0sec

- Eddy Merckx @ 1min 40sec

- Felice Gimondi @ 2min 12sec

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 2min 16sec

- José-Luis Uribezubia @ 2min 18sec

- Roger de Vlaeminck, Franco Bitossi, Constantino Conti @ 2min 19sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 2min 21sec

- Ole Ritter @ 2min 22sec

Sunday, May 26: Stage 10, Monte Carpegna - Modena, 205 km

- Patrick Sercu: 4hr 49min 20sec

- Marino Basso s.t.

- Roger de Vlaeminck s.t.

- Pierino Gavazzi s.t.

- Bruno Vicino s.t.

- Marcello Osler s.t.

- Julien van Lint s.t.

- Claudio Bartolotto s.t.

- Alessio Antonini s.t.

- Walter Avogadri s.t.

GC after Stage 10:

- José-Manuel Fuente: 51hr 44min 20sec

- Eddy Merckx @ 1min 40sec

- Felice Gimondi @ 2min 12sec

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 2min 14sec

- José-Luis Uribezubia @ 2min 18sec

- Roger de Vlaeminck, Franco Bitossi, Constantino Conti @ 2min 19sec

- Giambattista Barochelli @ 2min 21sec

- Ole Ritter @ 2min 22sec

Monday, May 27: Stage 11A, Modena - Il Ciocco, 153 km

![]() Major ascents: Radici, Il Ciocco

Major ascents: Radici, Il Ciocco

- José-Manuel Fuente: 4hr 40min 30sec

- Eddy Merckx @ 41sec

- Constantino Conti s.t.

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 47sec

- Franco Bitossi @ 49sec

- Wladimiro Panizza s.t.

- Gösta Pettersson @ 58sec

- Giovanni Battaglin s.t.

- Roger de Vlaeminck @ 1min 9sec

- Felice Gimondi s.t.

GC after Stage 11A

- José-Manuel Fuente

Monday, May 27: Stage 11B, Il Ciocco - Forte dei Marmi, 62 km

- Patrick Sercu: 1hr 43min 23sec

- Roger de Vlaeminck s.t.

- Marcello Osler s.t.

- Luciano Borgognoni s.t.

- Marino Basso s.t.

- Franco Bitossi s.t.

- Alessio Antonini s.t.

- Frans Mintjens s.t.

- Giacomo Bazzan s.t.

- Francesco Moser s.t.

GC after Stage 11B:

- José-Manuel Fuente: 58hr 8min 13sec

- Eddy Merckx @ 2min 21sec

- Constantino Conti @ 3min 0sec

- Franco Bitossi, Giambattista Baronchelli @ 3min 8sec

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 3min 12sec

- Felice Gimondi @ 3min 21sec

- Roger de Vlaeminck @ 3min 28sec

- Italo Zilioli @ 3min 58sec

- José-Luis Uribezubia @ 4min 3sec

Tuesday, May 28: Stage 12, Forte dei Marmi 40 km individual time trial

- Eddy Merckx: 49min 31sec

- Francesco Moser @ 27sec

- Gösta Pettersson @ 48sec

- Ole Ritter @ 1min 0sec

- Knut Knudsen @ 1min 13sec

- Felice Gimondi @ 1min 23sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 1min 26sec

- Roger de Vlaeminck s.t.

- Simone Fraccaro @ 1min 53sec

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 1min 54sec

GC after Stage 12:

- José-Manuel Fuente: 58hr 59min 47sec

- Eddy Merckx @ 18sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 2min 31sec

- Felice Gimondi @ 2min 41sec

- Francesco Moser @ @ 2min 49sec

- Roger de Vlaeminck @ 2min 51sec

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 3min 3sec

- Franco Bitossi @ 2min 9sec

- Constantino Conti @ 3min32sec

- Gösta Pettersson @ 4min 55sec

Wednesday, May 29: Rest Day after Brescia terrorist bombing. Rest day had originally been planned to come after stage 15.

Thursday, May 30: Stage 13, Forte dei Marmi - Pietra Ligure, 231 km

- Enrico Paolini: 6hr 23min 13sec

- Pierino Gavazzi s.t.

- Roger de Vlaeminck s.t.

- Marino Basso s.t.

- Alessio Antonini s.t.

- Patrick Sercu s.t.

- Gianfranco Foresti s.t.

- Roland Salm s.t.

- Francesco Moser s.t.

- Hennie Kuiper s.t.

GC after Stage 13:

- José-Manuel Fuente: 65hr 23min 0sec

- Eddy Merckx @ 18sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 2min 31sec

- Felice Gimondi @ 2min 41sec

- Francesco Moser @ 2min 49sec

- Roger de Vlaeminck @ 2min 51sec

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 3min 3sec

- Constantino Conti @ 3min 32sec

- Gösta Pettersson @ 4min 21sec

- Franco Bitossi @ 4min 29sec

Friday, May 31: Stage 14, Pietra Ligure - San Remo, 189 km

![]() Major ascents: Langan, Ghimbegna x 2

Major ascents: Langan, Ghimbegna x 2

- Giuseppe Perletto: 5hr 21min 58sec

- Wladimiro Panizza @ 21sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 40sec

- José-Luis Uribezubias.t.

- Vicente López-Carril s.t.

- Franco Bitossi @ 2min 18sec

- Roger de Vlaeminck s.t.

- Constantino Conti s.t.

- Francesco Moser s.t.

- Felice Gimondi s.t.

- Hennie Kuiper s.t.

- Eddy Merckx s.t.

- José-Manuel Fuente @ 10min 19sec

GC after Stage 14:

- Eddy Merckx: 70hr 47min 34sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 35sec

- Felice Gimondi @ 2min 23sec

- Francesco Moser @ 2min 31sec

- Roger de Vlaeminck @ 2min 33sec

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 2min 45sec

- Constantino Conti @ 3min 14sec

- Gösta Pettersson @ 4min 3sec

- Franco Bitossi @ 4min 11sec

- José-Luis Uribezubia @ 4min 52sec

Saturday, June 1: Stage 15, San Remo - Valenza, 206 km

- Ercole Gualazzini: 5hr 51min 54sec

- Bruno Zanoni s.t.

- Mauro Simonetti s.t.

- Martin "Cochise" Rodriguez s.t.

- Bruce Biddle s.t.

- Luciano Borgognoni @ 5sec

- Roger de Vlaeminck s.t.

- Patrick Sercu s.t.

- Franco Bitossi s.t.

- Marino Basso s.t.

GC after Stage 15:

- Eddy Merckx: 76hr 39min 33sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 35sec

- Felice Gimondi @ 2min 23sec

- Francesco Moser @ 2min 31sec

- Roger de Vlaeminck @ 2min 33sec

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 2min 45sec

- Constantino Conti @ 3min 14sec

- Gösta Pettersson @ 4min 3sec

- Franco Bitossi @ 4min 11sec

- José-Luis Uribezubia @ 4min 52sec

Sunday, June 2: Stage 16, Valenza - Monte Generoso, 158 km

![]() Major ascent: Monte Generoso

Major ascent: Monte Generoso

- José-Manuel Fuente: 4hr 20min 49sec

- Felice Gimondi @ 31sec

- Giuseppe Perletto s.t.

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 45sec

- Constantino Conti @ 1min 27sec

- Antoon Houbrechts @ 1min 40sec

- Gösta Pettersson @ 1min 41sec

- Wladimiro Panizza @ 1min 52sec

- Roger de Vlaeminck @ 2min 10sec

- Gianni Motta s.t.

GC after Stage 16:

- Eddy Merckx: 81hr 2min 53sec

- Felice Gimondi @ 33sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 41sec

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 1min 9sec

- Constantino Conti @ 2min 20sec

- Roger de Vlaeminck @ 2min 22sec

- Gösta Pettersson @ 3min 23sec

- Francesco Moser @ 3min 33sec

- Franco Bitossi @ 4min 17sec

- José-Luis Uribezubia @ 4min 52sec

Monday, June 3: Stage 17, Como - Iseo, 158 km

![]() Major Ascents: Gallo, San Fermo

Major Ascents: Gallo, San Fermo

- Santaigo Lazcano: 3hr 52min36sec

- José-Manuel Fuente s.t.

- Roger de Vlaeminck @ 13sec

- Francesco Moser s.t.

- Franco Bitossi s.t.

- Giovanni Battaglin s.t.

- Vicente López-Carril s.t.

- Constantino Conti s.t.

- Felice Gimondi s.t.

- Roberto Poggiali s.t.

GC after stage 17:

- Eddy Merckx: 84hr 55min 42sec

- Felice Gimondi @ 33sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 41sec

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 1min 9sec

- Constantino Conti @ 2min 20sec

- Roger de Vlaeminck @ 2min 22sec

- Gösta Pettersson @ 3min 23sec

- Francesco Moser @ 2min 33sec

- Franco Bitossi @ 4min 17sec

- José-Luis Uribezubia @ 4min 52sec

Tuesday, June 4: Stage 18, Iseo - Sella Valsugana, 190 km

![]() Major ascents: Sommo, Valsugana

Major ascents: Sommo, Valsugana

- Franco Bitossi: 5hr 45min 45sec

- Eddy Merckx s.t.

- Felice Gimondi s.t.

- Constantino Conti s.t.

- Francesco Moser s.t.

- Wladimiro Panizza s.t.

- José-Manuel Fuente s.t.

- Giovanni Battaglin s.t.

- Giambattista Baronchelli s.t.

- Vicente López-Carril s.t.

GC after stage 18:

- Eddy Merckx: 90hr 41min 27sec

- Felice Gimondi @ 33sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 41sec

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 1min 9sec

- Constantino Conti @ 2min 20sec

- Francesco Moser @ 3min 33sec

- Gösta Pettersson @ 3min 40sec

- Franco Bitossi @ 4min 17sec

- José-Manuel Fuente @ 5min 9sec

- José-Luis Uribezubia @ 7min 32sec

Wednesday, June 5: Stage 19, Borgo Valsugana - Pordenone, 146 km

- Enrico Paolini: 4hr 4min 39sec

- Knut Knudsen s.t.

- Marino Basso s.t.

- Günter Haritz s.t.

- Luciano Borgognoni s.t.

- Mauro Simonetti s.t.

- Luciano Rossignoli s.t.

- Wilmo Francioni s.t.

- Johan Ruch s.t.

- Pierino Gavazzi s.t.

GC after Stage 19:

- Eddy Merckx: 96hr 24min 7sec

- Felice Gimondi @ 33sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 41sec

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 1min 9sec

- Constantino Conti @ 2min 20sec

- Francesco Moser @ 3min 33sec

- Gösta Pettersson @ 3min 40sec

- Fraco Bitossi @ 4min 17sec

- José-Manuel Fuente @ 5min 9sec

- José-Luis Uribezubia @ 7min 32sec

Thursday, June 6: Stage 20, Pordenone - Tre Cime di Lavaredo (Cima Coppi), 163 km

![]() Major ascents: Monte Rest, Mauria, Tre Cime di Lavaredo

Major ascents: Monte Rest, Mauria, Tre Cime di Lavaredo

- José-Manuel Fuente: 5hr 40min 53sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 1min 18sec

- Constantino Conti @ 1min41sec

- Eddy Merckx @ 1min 47sec

- Vicente López-Carril s.t.

- Felice Gimondi s.t.

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 1min 58sec

- Franco Bitossi @ 2min 10sec

- Francisco Galdos @ 2min 27sec

- Giuseppe Perletto @ 2min 37sec

GC after Stage 20:

- Eddy Merckx: 100hr 28min 46sec

- Giambttista Baronchelli @ 12sec

- Felice Gimondi @ 33sec

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 1min 20sec

- Constantino Conti @ 2min 14sec

- José-Manuel Fuente @ 3min 22sec

- Franco Bitossi @ 4min 40sec

- Gösta Pettersson @ 5min 43sec

- Francesco Moser @ 6min 17sec

- Vicente López-Carril @ 8min 16sec

Friday, June 7: Stage 21, Misurina - Bassano del Grappa, 194 km

![]() Major ascents: Falzarego, Valles, Rolle, Grappa

Major ascents: Falzarego, Valles, Rolle, Grappa

- Eddy Merckx: 6hr 8min 8sec

- Francesco Moser s.t.

- Felice Gimondi s.t.

- Giambattista Baronchelli s.t.

- Constantino Conti s.t.

- José-Manuel Fuente s.t.

- Antoon Houbrechts @ 2min 12sec

- Vicente López-Carril s.t.

- Roger de Vlaeminck @ 3min 2sec

- Martin "Cochise" Rodriguez s.t.

GC after Stage 21:

- Eddy Merckx: 106hr 36min 54sec

- Giambattista Baronchelli @ 12sec

- Felice Gimondi 2 33sec

- Constantino Conti @ 2min 14sec

- José-Manuel Fuente @ 3min 22sec

- Giovanni Battaglin @ 4min 22sec

- Francesco Moser @ 6min 17sec

- Vicente López-Carril @ 10min 28sec

- Franco Bitossi @ 16min 5sec

- Gösta Pettersson @ 17min 8sec

Saturday, June 8: 22nd and Final Stage, Bassano del Grappa - Milano, 257 km

- Marino Basso: 6hr 31min 19sec

- Roger de Vlaeminck s.t.

- Franco Bitossi s.t.

- Ercole Gualazzini s.t.

- Francesco Moser s.t.

- Enrico Paolini s.t.

- Mauro Simonetti s.t.

- Gonzalo Aja s.t.

- Attilio Benfatto s.t.

- Luciano Rossignoli s.t.

1974 Giro d'Italia complete final General Classification

Complete startlist with racing numbers. All riders are Italian unless otherwise noted.

Molteni

Director Sportif: Giorgio Albani

All Molteni riders on this team were Belgian

- 1. Merckx, Eddy

- 2. Bruyere, Joseph

- 3. De Schoenmaecker, Joseph

- 4. Delcroix, Ludo

- 5. Huysmans, Joseph

- 6. Janssens, Ward

- 7. Mintjens, Frans

- 8. Rottiers, Karel

- 9. Van Schil, Victor

- 10. Van Vlierberghe,Albert

Bianchi-Campagnolo

Director Sportif: G. Ferretti

- 11. Gimondi, Felice

- 12. Basso, Marino

- 13. Cavalcanti, Giovanni

- 14. Houbrechts, Antoine (Belgium)

- 15. Rodriguez, Martin E. (Columbia)

- 16. Santanbrogio, Giacinto

- 17. Casteletti, Luigi

- 18. Foresti, Gianfranco

- 19. Parsani, Serge

- 20. Guerra, Pietro

Brooklyn

Director Sportif: Franco Cribori

- 31. De Vlaeminck, Roger (Belgium)

- 32. Bellini, Giancarlo

- 33. De Muynck, Roger (Belgium)

- 34. Gualazzini, Ercole

- 35. Panizza, Wladimiro

- 36. Passuelo, Adriano

- 37. Rota, Attilio

- 38. Sercu, Patrick (Belgium)

- 39. Van Lint, Julien (Belgium)

- 40. Van De Slagmollen, Herman (Belgium)

Dreherforte

Director Sportif: Luciano Pezzi

- 41. Borgononi, Luciano

- 42. Campagnari, Pietro

- 43. Dalla Bona, Giovanni

- 44. Fochesato, Gino

- 45. Landini, Mauro

- 46. Lanzafame, Mario

- 47. Maggioni, Enrico

- 48. Polidori, Giancarlo

- 49. Rossi, Tullio

- 50. Zilioli, Italo

Filcas

Director Sportif: Remigio Zanatta

- 51. Benfatto, Atillio

- 52. Botolotto, Claudio

- 53. Dall'anese, Efrem

- 54. Reybrouck, Wilfried (Belgium)

- 55. Fraccaro, Simone

- 56. Durante, Adriano

- 57. Peccolo, Alessio

- 58. Rossignoli, Luciano

- 59. Venturato, Luigi

- 60. Serlet, Erik (Belgium)

Filotex

Director Sportif: W. Bartolozzo

- 61. Moser, Francesco

- 62. Bergamo, Emanuele

- 63. Bergamo, Marcello

- 64. Caverzasi, Arnaldo

- 65. Colombo, Ugo

- 66. Giuliani, Donato

- 67. Fuchs, Joseph (Switzerland)

- 68. Poggiali, Roberto

- 69. Ritter, Ole (Denmark)

- 70. Solini, Roberto

Furzi

Director Sportif: C. Menicagli

- 71. Brunetti, Carlo

- 72. Varini, Giovanni

- 73. Moretti, Umberto

- 74. Scorza, Luigi

- 75. Tartoni, Giancarlo

- 76. Ravagli, Silano

- 77. Olsen, Reno (Denmark)

- 78. Zweifel, Albert (Switzerland)

- 79. Tosello, Guerini

- 80. Tamames, Agustin (Spain)

Jolliceramica

Director Sportif: M. Fontana

- 81. Antonini, Alessio

- 82. Battaglin, Giovanni

- 83. Bazzan, Giacomo

- 84. Brentegani, Enzo

- 85. Gavazzi, Pierino

- 86. Knudsen, Knut (Norway)

- 87. Nino, Rafael, Nino (Colombia)

- 88. Sutter, Ueli (Switzerland)

- 89. Vanzo, Dorino

- 90. Vicino, Bruno

KAS (All KAS riders on this team are Spanish)

Director Sportif: Anton Barrutia

- 91. Fuente, Manuel

- 92. Gonzales-Linares, Jose A.

- 93. Uribezubia, Jose Luis

- 94. Lazcano, Santiago

- 95. Lopez-Carril, Santiago

- 96. Galdos, Francisco

- 97. Martos, Antonio

- 98. Grande, Jose

- 99. Zubero, Luis

- 100. Aja, Gonzolo

Magnaflex

Director Sportif: P. Franchini

- 101. Pettersson, Gosta (Sweden)

- 102. Motta, Gianni

- 103. Branchi, Mario

- 104. Schiavon, Silvano

- 105. Crepaldi, Ottavio

- 106. Juliano, Gaetano

- 107. Quitarelli, Sandro

- 108. Chinetti, Alfredo

- 109. Mazziero, Daniele

- 110. Biddle, Bruce (New Zealand)

Rokado

Director Sportif: R. Wolfshohl

- 112. Gaida, Alfred (Germany)

- 113. Gilson, Roger (Luxembourg)

- 114. Haritz, Gunter (Germany)

- 117. Kuester, Karl Heinz (Germany)

- 118. Kuiper, Hennie (Netherlands)

- 119. Muddemann, Karl (Germany)

- 120. Ruch Johan (Germany)

Sammontana

- 121. Di Caterina, Pietro

- 122. Fabbri, Fabrizio

- 123. Fontanelli, Sigfrido

- 124. Francioni, Wilmo

- 125. Mori, Primo

- 126. Osler, Marcello

- 127. Perletto, Giuseppe

- 128. Riccomi, Walter

- 129. Salutini, Antonio

- 130. Simonetti, Mauro

SCIC

Director Sportif: C. Chiappano

- 131. Baronchelli, Gaetano

- 132. Baronchelli, Gian Battista

- 133. Bitossi, Franco

- 134. Conati, Luciano

- 135. Martella, Giovanni

- 136. Laghi, Renato

- 137. Paoloni, Enrico

- 138. Zanani, Bruno

- 139. Spinelli, Piero

- 140. Vercelli, Celestino

Zonca

Director Sportif: Ettore Milano

- 141. Avogadri, Walter

- 142. Bonancina, Claudio

- 143. Conti, Constantino

- 144. Favaro, Giorgio

- 145. Guadrini, Enrico

- 146. Pfenninger, Louis (Switzerland)

- 147. Pella, Adriano

- 148. Salm, Roland (Switzerland)

- 149. Savary, Rene (Switzerland)

- 150. Spahn, Erich (Switzerland)

The Story of the 1973 Giro d'Italia

This excerpt is from "The Story of the Giro d'Italia", Volume 2. If you enjoy it we hope you will consider purchasing the book, either print, eBook or audiobook. The Amazon link here will make the purchase easy.

The Italian economic miracle of the 1950s and 1960s was uneven, leaving most Italians dissatisfied with many aspects of how Italian government and society in general were ordered. The causes for the unease were many and there was a wide-spread belief that communist, specifically Maoist, thought held the solution to Italy's problems. As in much of the western world, student demonstrations in the late 1960s shook Italy badly. In most countries, left-wing unrest had calmed down by the early 1970s, but in Italy the demonstrations signaled more than just youthful anger. While Italy produced consumer goods in abundance, wages to buy these beautiful items remained low. Truly fearing revolution, industrialists and the government raised wages and gave workers more power. This real improvement in the Italian standard of living that took place over the next eight years left most of the Italian population reasonably content with their personal situation, even if still contemptuous of their government.

But the most militant of the left didn’t want the populace to be satisfied with televisions and cars, they wanted a revolution, and through the 1970s they escalated their efforts. By 1974 over a hundred separate groups were engaged in murderous acts of terrorism against judges, police, journalists and industrialists, causing a severe reaction within and without the government.

Right-wing groups with ties to the military and police formed and, trying to cause a public reaction against the leftists, bombed and murdered as well. Former prime minister Aldo Moro’s 1978 kidnapping and murder generated a sweeping clamp-down on the revolutionaries and by the early 1980s, violence for the most part was suppressed.

One prominent victim of the Red Guards, the most famous of the violent communist revolutionary groups, was Emilio Bozzi, who owned the legendary Legnano bike company, sponsor of Binda, Bartali and Coppi. After Bozzi’s 1974 assassination, his family sold the firm to Bianchi. In 2011, the Bozzi family reacquired the Legnano brand.

* * *

Starting in the Vatican City, 1974’s 22-stage Giro headed south down the Tyrrhenian coast, all the way to the instep of the Italian boot before heading east for Taranto. Then it traveled north along the Adriatic coast before heading inland to Modena. In the final week the Giro made a snaking journey around northern Italy for a final showdown in the Dolomites. The twentieth stage had the fearsome Tre Cime di Lavaredo for a hilltop finish and the next day the riders had to negotiate the Falzarego, Valles, Rolle and Monte Grappa climbs.

Fuente and his KAS boys came to have another go at Merckx, Fuente having been ill-prepared the year before and uncompetitive in the mountains until the final days. Using the form he gained in the 1973 Giro, he had gone on that year to win the Tour of Switzerland and come in third in the Tour. This year he was ready, having won the Vuelta earlier in the spring with two stage wins.

Merckx, on the other hand, for the first time since 1965 (his first year as a professional), did not win a single spring Classic.

The rest of the roster of contenders was mostly a list of the usual suspects: Gimondi, Panizza, Moser, Battaglin, Pettersson and Motta. There was one fresh face, Giambattista Baronchelli, who had won both the Tour de l’Avenir and the Girobio (the amateur or “Baby” Giro) in 1973. Hired by SCIC, he was in his first professional Grand Tour.

Gimondi was the current World Road Champion after winning the final sprint from Merckx, Luis Ocaña and Freddy Maertens. Gimondi still had the legs in March when he won Milan–San Remo, Coppi-style. He initiated an early break, battered it senseless and rode solo for 25 kilometers to finish nearly two minutes ahead of Eric Leman, the largest gap since Fausto Coppi beat Vito Ortelli by more than four minutes in 1949.

The first stage ended in a great rush that should have been a showcase for the big names in speed, Basso, Sercu, Bitossi and de Vlaeminck, but a man who had just turned pro upstaged them all: Wilfried Reybrouck zipped up the side of the road with 400 meters to go, holding off a hard-charging de Vlaeminck.

When Vittorio Adorni had needed a couple of Belgian flahutes for his Filcas squad, he asked Guido Reybrouck, an accomplished and well-known professional, for recommendations. Guido suggested his brother Wilfried. That’s how an unknown neo-pro came to stun the cycling establishment when he donned the maglia rosa.

The next day ended in Pompei. A major strike didn’t fulfill its threat to close the road through Naples, but the wary pack stayed together for security. Young Reybrouck kept his lead.

The hilly area of Sorrento gave the climbers their first chance to show their form in stage three. Fuente promised to make trouble for the others and was true to his word. He left them behind on Monte Faito, an eleven-kilometer climb with patches of eleven-percent gradient. Merckx wasn’t able to stay with the first two groups of pursuers, but he was a good descender and connected with the second group of chasers, finishing 42 seconds behind stage winner Fuente, the new leader.

And Reybrouck? He got a hard lesson in the intensity of climbing in Grand Tours. Shelled on an early minor climb, he finished outside the time limit. One day he was a young hero wearing the coveted maglia rosa, the next day he was in tears packing his bags for home.

From there, the Giro went to the bottom of the peninsula and turned northward. Each day was almost a carbon copy of the previous one, the racers riding slowly until the final 50 or so kilometers and then winding the speed up to almost the limit of human performance before unleashing a wild sprint. The master of the last-minute escape, Franco Bitossi, managed to foil the sprinters at the end of stage six, holding off the hard-charging pack by two seconds. Through these stages, Fuente kept his lead and de Vlaeminck remained the points leader.

The next day stage nine ended with a climb and descent of Monte Carpegna in Le Marche, not far from San Marino. Once the pack reached the mountain Fuente came out of the saddle, gave his pedals a hard push and was gone. Merckx chased, but the Fuente of 1974 was a far better rider than the Fuente of 1973. Because of the hard rain, Merckx chose not to take any serious risks on the way down the mountain, allowing the Spaniard to add another 65 seconds to his lead.

The General Classification at this point:

1. José-Manuel Fuente

2. Eddy Merckx @ 1 minute 40 seconds

3. Felice Gimondi @ 2 minutes 12 seconds

4. Giovanni Battaglin @ 2 minutes 16 seconds

5. José-Luis Uribezubia @ 2 minutes 18 seconds

Big-time sprinters sometimes make public their plans to ride only a few flat stages before retiring from a Grand Tour, generally outraging the organizers. Patrick Sercu announced that he would retire from the Giro after stage fourteen in San Remo and prepare for the Tour de France. Torriani was especially enraged because Sercu told television audiences that his team boss had approved of the plan. Torriani called Sercu’s sponsor, Giorgio Perfetti of Brooklyn chewing gum, telling him he must punish Sercu by sending him back to Belgium now. Perfetti refused, telling Sercu that he should win another stage before quitting, just to twist Torriani’s tail.

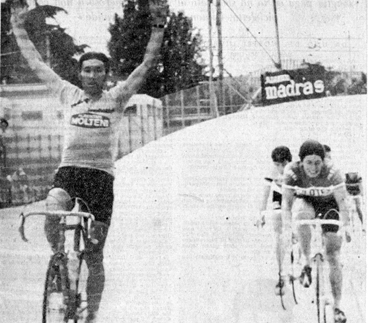

Italian champion Enrico Paolini and José-Manuel Fuente

Stage eleven’s morning half-stage had a finish atop the steep Il Ciocco climb. Again Fuente jumped and no one could hold his wheel. Merckx chased, but could get no closer than 41 seconds. That afternoon Sercu won that third stage Perfetti asked of him.

The next day was a 40-kilometer individual time trial. In winning the stage, Merckx erased all but 18 seconds of the lead Fuente had spent almost 2 weeks accumulating. Feeling that a bullet had just missed his ear, Fuente said, “Today I won the Giro.” With the Dolomite stages coming, he predicted that this year Merckx would see that Fuente was the superior rider.

The Giro’s original plan was to have a rest day in San Remo after stage fourteen. But on the afternoon of stage twelve, news came of the outrage in Brescia. During an anti-fascist demonstration, the right-wing group Ordine Nuovo set off a bomb that killed six. The government declared a national day of mourning and the Giro decided to stay put and have its rest day two days early.

Stage fourteen, a run up the Ligurian coast using many of the same roads and climbs as Milan–San Remo, is a day famous in the history of racing. The weather was terrible with hard, pouring rain. The organizers, feeling that the Passo del Ceppo would be too dangerous in the wet, changed the day’s route. It was extended by 24 kilometers, making it 189 kilometers and now included two ascents of the Ghimbegna.

After the first time over, a small group that included Fuente teammate López-Carril broke away. On the second ascent the remaining top riders, including Merckx, Gimondi and Fuente, separated themselves from the peloton. Fuente, having the lead, decided to ride the stage defensively. If Merckx wanted to win the Giro, he would have to take it away from Fuente on Fuente’s own turf, the mountains.

Seeking the riders up the road, Baronchelli blasted away from the Merckx/Fuente group and after a short hesitation, Merckx and Gimondi took off after the Italian. Then fans watching the race got the shock of their lives. Fuente wasn’t with Merckx and Gimondi, he was off the back! He quickly lost two minutes. Fuente was suffering a dramatic défaillance. His final time loss for the day was 10 minutes 19 seconds.

On the day he had planned to make the Giro his, Fuente lost the race. Why?

“I forgot the most important thing, which was to get plenty to eat. Perhaps it was because of the bad weather or because I had been feeling so strong…it was all well planned but I failed because I forgot to eat.” It’s not an unknown failing. Anquetil lost the Giro in 1959 because he didn’t eat and Lance Armstrong got into trouble more than once for the same reason.

Merckx became the maglia rosa:

1. Eddy Merckx

2. Giambattista Baronchelli @ 35 seconds

3. Felice Gimondi @ 2 minutes 23 seconds

4. Francesco Moser @ 2 minutes 31 seconds

5. Roger de Vlaeminck @ 2 minutes 33 seconds

Stage sixteen finished at the top of the 1,209-meter-high Monte Generoso near Como, just inside the Swiss border. As he predicted and was expected, Fuente escaped on the lower slopes of the eleven-kilometer climb and no one was able to stay with him. But Merckx seemed worried. Midway through the stage he broke his left toe clip, but refused to get the defect repaired. De Vlaeminck rode up to him, advising Merckx to get his bike fixed, given the coming climb. But afraid to stop, Merckx pressed on, finishing fifteenth that day, 2 minutes 21 seconds behind Fuente. Gimondi had a fine day, coming in second, only 31 seconds behind the flying Spaniard. This moved Gimondi up to second place in the Overall.

The next day was also mountainous and again Fuente was on the hunt. He sent two of his men up ahead and eventually hooked up with one of them, Lazcano. The pair hot-footed it for the finish with Merckx, Gimondi, Moser and others in pursuit. The Spanish duo barely held their lead to the end with Fuente sitting up just before the line to let his hard-working helper take the stage. For the four hours of hard work Fuente had gained 13 seconds.

It was raining for the start of stage twenty with its ascent of the Forcella di Monte Rest followed by the milder Passo dell Mauria and then a finish at the top of the Tre Cime di Lavaredo. Merckx had grown disgusted with the help the tifosi had given the Italian riders on the climbs and worried that there might be a repeat of the 1967 episode on the same climb, where the riders had cheated so flagrantly that Torriani had annulled the stage.

Meanwhile, framebuilder Ernesto Colnago, supplier of frames to Merckx’s Molteni team as well as Baronchelli’s SCIC squad, had hatched a plan. Historian Beppe Conti explained that Colnago was good friends with Merckx, having built the special bike Merckx used to win the World Hour Record. Colnago suggested that Merckx let the young Baronchelli have a bit of glory on the Tre Cime climb, and after the young SCIC rider had made the tifosi happy with some time alone on the famous ascent, Merckx could close the gap and win the stage. Despite Baronchelli’s high placing, Merckx is said to have agreed to the plan, largely because of his friendship with Colnago.

Ten kilometers from the top, Fuente unleashed a blistering attack. Merckx answered, with Baronchelli, Battaglin, López-Carril and Tino Conti coming along.

Then Baronchelli attacked. This might have been the most dangerous move of the entire Giro because Baronchelli was less than a minute behind Merckx in the General Classification. Merckx clawed his way back up to the young Italian and then Baronchelli went again. Had Merckx relaxed a bit at some point and let the Italian get a gap? It is written that he did, but I remain unsure. Baronchelli was riding far better than anyone anticipated.

Despite Merckx’s desperate attempts to catch him, Baronchelli was well and truly gone. Fuente won the stage, his fifth this year and was now sitting in fifth place, 3 minutes 22 seconds behind Merckx. And Baronchelli? He was now in second, only 12 seconds behind Merckx.

The close standings made it likely that the twenty-first stage with its four climbs would be a rough day in the Dolomites. Fuente promised to make it so; it was his last chance to take the lead. It was on the final climb of the day, the 24-kilometer long ascent of Monte Grappa that the Giro was decided.

Eddy Merckx wins stage 21 in front of Francesco Moser and Felice Gimondi.

Fuente was desperate to get away and did three hard accelerations before he was able to drop Merckx’s gregari Jos Huysmans and Jos De Schoenmaecker. Merckx bided his time, letting Baronchelli and Gimondi mount the chase. And still he waited. Finally Merckx went to the front of the chasing group and dragged them at a punishing pace to the top. When Merckx had started the chase Fuente had a lead of 2 minutes 40 seconds and at the summit it was down to just 35 seconds. With the long descent into Bassano del Grappa, Fuente’s goose was cooked. Merckx won the stage and seemed to seal his Giro victory.

But not so fast, said Fuente. The final stage of a Grand Tour is usually a ceremonial promenade, but not this time. Fuente attacked hard and forced Merckx himself to mark him. Separated from the pack, Fuente did all the work with a concerned Merckx sitting on his wheel. After the lead had grown to 80 seconds, Merckx asked his director, Giorgio Albani, to have the Molteni team shut down the break. Merckx was worried that with a determined Fuente riding away from the peloton, a flat tire or some other difficulty might cause him to lose the Giro. Fuente was brought back, but the indomitable Spaniard tried two more times to get away. It was no use and the pack was together for a sprint on the Vigorelli velodrome.

The Giro was again Merckx’s. This was his fifth, equaling the record of Alfredo Binda (1925, ’27, ’28, ’29, ’33) and Fausto Coppi (1940, ’47, ’49, ’52, ’53). It was a slim win, not gained with the dominating power of previous years. This was a terrific Giro, but Italian RAI television, fearing another boring, dominating Merckx march across Italy, chose to show only highlights from some of the stages.

While Merckx may have had a disappointing spring, his 1974 turned out to be historic. He won the Giro, the Tour of Switzerland, the Tour de France and the World Road Championship. No one before or since has done this. The closest was Stephen Roche when he won the Giro, Tour de France, Tour of Romandie and the World’s in 1987. Merckx had one more good year in him, but never again would he win the Giro or the Tour.

Final 1974 Giro d’Italia General Classification:

1. Eddy Merckx (Molteni) 113 hours 8 minutes 13 seconds

2. Giambattista Baronchelli (SCIC) @ 12 seconds

3. Felice Gimondi (Bianchi) @ 33 seconds

4. Constantino “Tino” Conti (Zonca) @ 2 minutes 14 seconds

5. José-Manuel Fuente (KAS) @ 3 minutes 22 seconds

Climbers’ Competition:

1. José-Manuel Fuente (KAS): 510 points

2. Eddy Merckx (Molteni): 330

3. Santiago Lazcano (KAS): 230

Points Competition:

1. Roger de Vlaeminck (Brooklyn): 265 points

2. Franco Bitossi (SCIC): 209

3. José-Manuel Fuente (KAS): 171

.