1989 Giro d'Italia

72nd edition: May 21 - June 11

Results, stages with running GC, photos, video and history

1990 Giro | 1988 Giro | Giro d'Italia Database | 1989 Giro Quick Facts | 1989 Giro d'Italia Final GC | Stage results with running GC | The Story of the 1989 Giro d'Italia | Video

Map of the 1989 Giro d'Italia

3,428 km raced at an average speed of 36.55 km/hr

197 starters and 141 classified finishers

Erik Breukink, who came close to winning the 1988 Giro, took the lead after the stage 10 time trial.

He lost the maglia rosa in stage 15, the Queen Stage with five major passes. It was raced in cold, foggy rain, and Breukink lost almost six minutes because of hunger knock.

Laurent Fignon, who had suffered several years of poor form, captured the lead, which he kept to the end.

Greg LeMond, who had had his own problems becoming competitive, astounded everyone with a second place in the final time trial.

LeMond went on to win both the Tour de France and the World Championships in 1989.

Bill & Carol McGann's book The Story of the Tour de France, Vol 1: 1903 - 1975 is available as an audiobook here.

1989 Giro d'Italia Complete Final General Classification:

Laurent Fignon (Super U-Raleigh) 93hr 30min 16sec

Laurent Fignon (Super U-Raleigh) 93hr 30min 16sec- Flavio Giupponi (Malvor-Sidi) @ 1min 15sec

- Andy Hampsten (7-Eleven) @ 2min 46sec

- Erik Breukink (Panasonic) @ 5min 2sec

- Franco Chioccioli (Del Tongo) @ 5min 43sec

- Urs Zimmermann (Carrera) @ 6min 28sec

- Claude Criquielion (Hitachi) @ 6min 34sec

- Marco Giovannetti (Seur) @ 7min 44sec

- Stephen Roche (Fagor) s.t.

- Marino Lejarreta (Caja Rural) @ 8min 9sec

- Vladimir Pulnikov (Alfa Lum) @ 9min 50sec

- Roberto Conti (Selca-Conti-Ciclolinea) @ 10min 3sec

- Phil Anderson (TVM-Van Schilt) @ 12min 6sec

- Jesper Skibby (TVM-Van Schilt) @ 12min 13sec

- Moreno Argentin (Gewiss-Bianchi) @ 12min 16sec

- Piotr Ugramov (Alfa Lum) @ 14min 27sec

- Franco Vona (Chateau d'Ax-Salotti) @ 14min 39sec

- Luis Alberto Herrera (Cafe de Colombia-Mavic) @ 16min 19sec

- Jokin Mujika (Caja Rural) @ 22min 2sec

- Jon Unzaga (Seur) @ 24min 56sec

- José Samuel Cabrera (Cafe de Colombia-Mavic) @ 31min 29sec

- Eddy Schepers (Fagor) @ 31min 43sec

- Gianni Bugno (Chateau d'Ax-Salotti) @ 32min 23sec

- José Salvador Sanchis (Caja Rural) @ 32min 29sec

- Jesus Blanco Vilar (Seur) @ 34min 28sec

- Stefano Tomasini (Pepsi Cola-Alba Cucine) @ 36min 21sec

- Luca Gelfi (Del Tongo) @ 37min 39sec

- Maurizio Fondriest (Del Tongo) @ 38min 52sec

- Peter Winnen (Panasonic) @ 39min 54sec

- Jos van Aert (Hitachi) @ 40min 50sec

- Laurent Biondi (Fagor) @ 41min 27sec

- Ennio Salvador (Gewiss-Bianchi) @ 44min 39sec

- Julio Cesar Cadena (Cafe de Colombia-Mavic) @ 45min 43sec

- Jos Haex (Hitachi) @ 46min 26sec

- Jure Pavlic (Carrera) @ 49min 14sec

- Mauro-Antonio Santaromita (Pepsi Cola-Alba Cucine) @ 49min 58sec

- Dominique Garde (Super U-Raleigh) @ 52min 9sec

- Rolf Järmann (Frank-Toyo) @ 53min 50sec

- Greg LeMond (ADR-Bottecchia) @ 54min 23sec

- John Carlsen (Fagor) @ 54min 50sec

- Alessandro Pozzi (Chateau d'Ax-Salotti) @ 55min 15sec

- Serguei Ouslamine (Alfa Lum) @ 56min 28sec

- Maurizio Rossi (Jolly Componibili) @ 57min 43sec

- Henry Cardenas (Cafe de Colombia-Mavic) @ 58min 28sec

- Jesus Arambarri (Caja Rural) @ 58min 32sec

- Claudio Chiappucci (Carrera) @ 59min 54sec

- Jacques Decrion (Super U-Raleigh) @ 1hr 3min 24sec

- Acacio Da Silva (Carrera) @ 1hr 4min 9sec

- Bruno Beyère (Hitachi) @ 1hr 5min 44sec

- Maurizio Piovani (Malvor-Sidi) @ 1hr 6min 21sec

- Jean-Philippe Vandenbrande (TVM-Van Schilt) @ 1hr 13min 49sec

- Robert Forest (Fagor) @ 1hr 16min 50sec

- Silvano Contini (Malvor-Sidi) @ 1hr 17min 47sec

- Serguei Soukhoroutchenkov (Alfa Lum) @ 1hr 18min 21sec

- Marino Amadori (Del Tongo) @ 1hr 20min 24sec

- Giancarlo Perini (Carrera) @ 1hr 22min 26sec

- Eric Salomon (Super U-Raleigh) @ 1hr 23min 22sec

- Nikolai Golovatenko (Alfa Lum) @ 1hr 27min 31sec

- Jeff Pierce (7-Eleven) @ 1hr 28min 23sec

- Miguel Arroyo (ADR-Bottecchia) @ 1hr 29min 48sec

- Gianluca Brugnami (Jolly Componobili) @ 1hr 29min 57sec

- Werner Stutz (Frank-Toyo) @ 1hr 31min 53sec

- Gerhard Zadrobilek (7-Eleven) @ 1hr 33min 21sec

- Dag-Otto Lauritzen (7-Eleven) @ 1hr 34min 47sec

- Jean-Louis Peillon (Super U-Raleigh) @ 1hr 35min 31sec

- Martin Schalkers (TVM-Van schilt) @ 1hr 35min 37sec

- Lech Piasecki (Malvor-Sidi) @ 1hr 37min 58sec

- Massimo Ghirotto (Carrera) @ 1hr 38min 12sec

- Henk Lubberding (Panasonic) @ 1hr 41min 18sec

- Alfons de Wolf (ADR-Bottecchia) @ 1hr 42min 46sec

- Jesper Worre (Cafe de Colombia-Mavic) @ 1hr 45min 27sec

- José-Rafael Garcia (Seur) @ 1hr 45min 41sec

- Hendrik De Vos (Hitachi) @ 1hr 45min 42sec

- Eric Van Lancker (Panasonic) @ 1hr 46min 52sec

- Giuseppe Saronni (Malvor-Sidi) @ 1hr 47min 13sec

- Daan Luyckx (TVM-Van Schilt) @ 1hr 48min 14sec

- Czeslaw Lang (Malvor-Sidi) @ 1h 48min 27sec

- Angelo Lecchi (Del Tongo) @ 1hr 49min 34sec

- Bruno Cenghialta (Ariostea) @ 1hr 53min 18sec

- Vasili Jdanov (Alfa Lum) @ 1hr 53min 40sec

- Francisco Espinosa (Seur) @ 1hr 57min 55sec

- Fabio Bordonali (Malvor-Sidi) @ 1hr 58min 11sec

- Angelo Canzonieri (Pepsi Cola-Alba Cucine) @ 2hr 1min 47sec

- Paul Kimmage (Fagor) @ 2hr 4min 4sec

- Rodolfo Massi (Atala-Campagnolo) @ 2hr 4min 32sec

- Bjarne Riis (Super U-Raliegh) @ 2hr 7min 40sec

- Salvatore Cavallaro (Seur) @ 2hr 8min 0sec

- Stefano Giuliani (Jolly Componibili) @ 2hr 9min 57sec

- Eduardo Rocchi (Selca-Conti-Ciclolinea) @ 2hr 10min 22sec

- Francesco Rossignoli (Fagor) @ 2hr 10min 23sec

- Luciano Boffo (Jolly Componibili) @ 2hr 11min 58sec

- Mario Chiesa (Carrera) @ 2hr 12min 29sec

- Andrei Tchmil (Alfa Lum) @ 2hr 14min 23sec

- Luciano Rabbotini (Ariostea) @ 2hr 19min 33sec

- Claudio Corti (Chateau d'Ax-Salotti) @ 2hr 23min 0sec

- Marco Bergamo (Del Tongo) @ 2hr 24min 36sec

- Luigi Bielli (Del Tongo) @ 2hr 28min 1sec

- José Antonio Sanchez (Caja Rural) @ 2hr 29min 57sec

- Jan Siemons (TVM-Van Schilt) @ 2hr 31min 6sec

- Karl Kalin (Frank-Toyo) @ 2hr 31min 34sec

- Marco Zen (Del Tongo) @ 2hr 32min 5sec

- Ron Kiefel (7-Eleven) @ 2hr 32min 53sec

- Stefan Morjean (Hitachi) @ 2hr 34min 4sec

- Rob Kleinsman (TVM-Van Schilt) @ 2hr 38min 45sec

- John Talen (Panasonic) @ 2hr 40min 56sec

- Jurg Bruggmann (Frank-Toyo) @ 2hr 42min 16sec

- Christian Henn (Carrera) @ 2hr 45min 22sec

- Silvio Martinello (Atala-Campagnolo) @ 2hr 48min 5sec

- Giuseppe Petito (Ariostea) @ 2hr 49min 2sec

- Giovanni Fidanza (Chateau d'Ax-Salotti) @ 2hr 50min 23sec

- Javier Garciandia (Caja Rural) @ 2hr 56min 0sec

- Stefano Zanatta (Chateau d'Ax-Salotti) @ 3hr 1min 28sec

- Marcel Arntz (Caja Rural) @ 3hr 1min 46sec

- Bob Roll (7-Eleven) @ 3hr 2min 35sec

- Kurt Steinmann (Frank-Toyo) @ 3hr 5min 47sec

- Thierry Marie (Super U-Raleigh) @ 3hr 6min 15sec

- Paul Popp (Caja Rural) @ 3hr 10min 39sec

- Christian Thary (Pepsi Cola-Alba Cucine) @ 3hr 11min 49sec

- Danilo Gioia (Atala-Campagnolo) @ 3hr 11min 59sec

- Daniele Del Ben (Jolly Componibili) @ 3hr 14min 14sec

- Paolo Cimini (Jolly Componibili) @ 3hr 15min 59sec

- Hans-Rudi Märki (Panasonic) @ 3hr 18min 50sec

- Giuseppe Calcaterra (Atala) @ 3hr 22min 48sec

- Luis-Maria Diaz de Otazu (Seur) @ 3hr 23min 15sec

- Frank Hoste (ADR-Bottecchia) @ 3hr 28min 15sec

- Pius Schwarzentruber (Frank-Toyo) @ 3hr 30min 26sec

- Paolo Rosola (Gewiss-Bianchi) @ 3hr 31min 34sec

- Adriano Baffi (Ariostea) @ 3hr 31min 50sec

- Dick Dekker (Caja Rural) @ 3hr 36min 41sec

- Claudio Rio (Selca-Conti-Ciclolinea) @ 3hr 39min 13sec

- Mario Scirea (Cafe de Colombia-Mavic) @ 3hr 40min 30sec

- Jean-Paul van Poppel (Panasonic) @ 3hr 47min 34sec

- Noël Szostek (ADR-Bottecchia) @ 3hr 48min 36sec

- Stefanino Cecini (Jolly Componibili) @ 3hr 55min 15sec

- Daniele Bruschi (Atala-Campagnolo) @ 3hr 55min 39sec

- Johan Lammerts (ADR-Bottecchia) @ 3hr 57min 43sec

- Simone Bruscoli (Pepsi Cola-Alba Cucine) @ 4min 1min 52sec

- Alessio Di Basco (Pepsi Cola-Alba Cucine) @ 4hr 2min 13sec

- Davide Carli (Selca-Conti-Ciclolinea) @ 4hr 3min 19sec

- Stefano Allocchio (Malvor-Sidi) @ 4hr 11min 3sec

- Patrizio Gambirasio (Selca-Conti-Ciclolinea) @ 4hr 21min 10sec

Points Classification:

Giovanni Fidanza (Chateau d'Ax-Salotti): 172 points

Giovanni Fidanza (Chateau d'Ax-Salotti): 172 points- Laurent Fignon (Super U-Raleigh): 139

- Erik Breukink (Panasonic): 128

- Maurizio Fondriest (Del Tongo): 116

- Acacio Da Silva (Carrera): 111

Climbers' Competition:

Luis Herrera (Cafe de Colombia-Mavic): 70 points

Luis Herrera (Cafe de Colombia-Mavic): 70 points- Stefano Giuliani (Jolly Componibili): 38

- Jure Pavlič (Carrera), Henry Cardenas (Cafe de Colombia): 34

- Flavio Giupponi (Malvor-Sidi): 28

Young Rider:

Vladimir Poulnikov (Alfa Lum) 93hr 40min 6sec

Vladimir Poulnikov (Alfa Lum) 93hr 40min 6sec- Piotr Ugrumov (Alfa Lum) @ 4min 37sec

- Luca Gelfi (Del Tongo) @ 27min 49sec

- Jos Van Aert (Hitachi) @ 31min 0sec

- Jure Pavlič (Carrera) @ 39min 24sec

Team Classification:

- Fagor: 279hr 59min 13sec

- Caja Rural @ 13min 27sec

- Alfa Lum @ 16min 11sec

1989 Giro stage results with running GC:

Sunday, May 21: Stage 1, Taormina - Catania, 123 km

- Jean-Paul van Poppel: 2hr 43min 35sec

- Giovanni Fidanza s.t.

- Adriano Baffi s.t.

- Maurizio Fondriest s.t.

- Frank Hoste s.t.

- Rolf Sørensen s.t.

- Fabiano Fontanelli s.t.

- Luciano Boffo s.t.

- Silvio Martinello s.t.

- Davis Phinney s.t.

Monday, May 22: Stage 2, Catania - Etna, 132 km

![]() Major ascent: Mt. Etna

Major ascent: Mt. Etna

- Acacio Da Silva: 3hr 32min 38sec

- Luis Herrera s.t.

- Tony Rominger s.t.

- Marino Lejarreta s.t.

- Ivan Ivanov s.t.

- Laurent Fignon s.t.

- Silvano Contini s.t.

- Gianni Bugno s.t.

- Claude Criquielion s.t.

- Piotr Ugrumov s.t.

GC after Stage 2:

- Acacio Da Silva: 6hr 15min 58sec

- Luis Herrera @ 8sec

- Tony Rominger @ 12sec

- Piotr Ugrumov, Gianni Bugno, Laurent Fignon, Marino Lejarreta, Stephen Roche, Claude Criquielion, Silvano Contini, Ivan Ivanov @ 19sec

Tuesday, May 23: Stage 3, Villafranca Terme - Messina 32 km team time trial (cronometro a squadra)

- Ariostea (Elli, Carcano, Cesarini, Baffi, Cenghialta, Sørensen): 37min 0sec

- Malvor-Sidi @ 16sec

- Panasonic @ 16sec

- Del Tongo @ 34sec

- Carrera @ 49sec

- TVM-Van Schilt @ 1min 3sec

- Super U-Raleigh @ 1min 31sec

- Atala-Campagnolo @ 2min 7sec

- Gewiss-Bianchi @ 2min 8sec

- Fagor @ 2min 11sec

GC after Stage 3:

- Silvano Contini: 6hr 53mn 33sec

- Acacio Da Silva @ 14sec

- Flavio Giupponi @ 15sec

- Erik Breukink @ 23sec

- Maurizio Fondriest @ 27sec

- Urs Zimmermann @ 48sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 49sec

- Stephen Roche @ 55sec

- Alberto Elli @ 57sec

- Tony Rominger @ 58sec

Wednesday, May 24: Stage 4, Scilla - Cosenza, 204 km

![]() Major ascents: San Elia, Acquabona

Major ascents: San Elia, Acquabona

- Rolf Jaermann: 5hr 49min 40sec

- Rolf Sørensen @ 14sec

- Acacio Da Silva s.t.

- Luciano Boffo s.t.

- Giuseppe Saronni s.t.

- Salvatore Cavallaro s.t.

- Silvio Martinello s.t.

- Greg LeMond s.t.

- Angelo Canzonieri s.t.

- Davide Cassani s.t.

GC after Stage 4:

- Silvano Contini: 12hr 53min 27sec

- Acacio Da Silva @ 11sec

- Flavio Giupponi @ 15sec

- Erik Breukink @ 23sec

- Maurizio Fondriest @ 49sec

- Urs Zimmermann @ 48sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 49sec

- Stephen Roche @ 55sec

- Alberto Elli @ 57sec

- Tony Romnger @ 58sec

Thursday, May 25: Stage 5, Cosenza - Potenza, 276 km

![]() Major ascents: Sella Lata, Scrivano

Major ascents: Sella Lata, Scrivano

- Stefano Giuliani: 6hr 20min 49sec

- Maurizio Fondriest @ 44sec

- Phil Anderson s.t.

- Rolf Sørensen s.t.

- Dimitri Konyshev s.t.

- Acacio Da Silva s.t.

- Flavio Giupponi s.t.

- Jesus Blanco Villar s.t.

- Piotr Ugrumov s.t.

- Silvano Contini s.t.

GC after Stage 5:

- Silvano Contini: 21hr 15min 0sec

- Acacio Da Silva @ 11sec

- Flavio Giupponi @ 15sec

- Maurizio Fondriest @ 20sec

- Erik Breukink @ 23sec

- Urs Zimmermann @ 48sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 49sec

- Stephen Roche @ 55sec

- Alberto Elli @ 57sec

- Tony Rominger @ 58sec

Friday, May 26: Stage 6, Potenza - Campobasso, 223 km

![]() Major ascents: Romito, Monte Carruozo

Major ascents: Romito, Monte Carruozo

- Stephen Joho: 6hr 6min 45sec

- Claudio Chiappucci @ 3min 15sec

- Ennio Salvador @ 3min 18sec

- Maurizio Fondriest @ 3min 20sec

- Johan Van der Velde s.t.

- Jürg Bruggmann s.t.

- Acacio Da Silva s.t.

- Fabio Fontanelli s.t.

- Rolf Sørensen s.t.

- Dimitri Konyshev s.t.

GC after Stage 6:

- Silvano Contini: 27hr 25min 5sec

- Acacio Da Silva @ 11sec

- Flavio Giupponi @ 15sec

- Maurizio Fondriest @ 20sec

- Erik Breukink @ 23sec

- Urs Zimmermann @ 48sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 49sec

- Stephen Roche @ 55sec

- Alberto Elli @ 57sec

- Tony Rominger @ 58sec

Saturday, May 27: Stage 7, Isernia - Roma, 208 km

- Urs Freuler: 5hr 31min 13sec

- Mario Cipollini s.t.

- Giovanni Fidanza s.t.

- Paolo Rosola s.t.

- Davis Phinney s.t.

- Alessio Di Basco s.t.

- Stefano Allochio s.t.

- Frank Hoste s.t.

- Peter Pieters s.t.

- Maurizio Fondriest s.t.

GC after Stage 7:

- Silvano Contini: 32hr 56min 18sec

- Acacio Da Silva @ 11sec

- Flavio Giupponi @ 15sec

- Maurizio Fondriest @ 20sec

- Erik Breukink @ 23sec

- Urs Zimmermann @ 48sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 49sec

- Stephen Roche @ 55sec

- Alberto Elli @ 57sec

- Tony Rominger @ 58sec

Sunday, May 28: Stage 8, Roma - Gran Sasso d'Italia, 183 km

![]() Major ascents: Corno, Grean Sasso d'Italia

Major ascents: Corno, Grean Sasso d'Italia

- John Carlsen: 5hr 21min 42sec

- Luis Herrera @ 29sec

- Marino Lejarreta s.t.

- Erik Breukink s.t.

- Jon Unzaga @ 35sec

- Dimitri Konyshev s.t.

- Laurent Fignon s.t.

- Stephen Roche s.t.

- roberto Conti s.t.

- Andrew Hampsten s.t.

GC after Stage 8:

- Erik Breukink: 38hr 18min 50sec

- Acacio Da Silva @ 1sec

- Silvano Contini @ 12sec

- Flavio Giupponi @ 27sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 32sec

- Luis Herrera @ 35sec

- Stephen Roche, Urs Zimmermann @ 38sec

- Maurizio Fondriest @ 42sec

- Piotr Urgumov @ 49sec

Monday, May 29: Stage 9, L'Aquila - Gubbio, 221 km

![]() Major ascents: Canapine, Soglio, Colfiorito

Major ascents: Canapine, Soglio, Colfiorito

- Bjarne Riis: 6hr 0min 15sec

- Dimitri Konyshev s.t.

- Ennio Galleschi s.t.

- Werner Stutz @ 10sec

- Salvatore Cavallaro s.t.

- Gianni Bugno s.t.

- Mauro Santaromita s.t.

- Rolf Sørensen @ 20sec

- Giovanni Fidanza @ 27sec

- Acacio Da Silva s.t.

GC after Stage 8:

- Acacio Da Silva: 44hr 19min 28sec

- Erik Breujink @ 4sec

- Silvano Contini @ 16sec

- Flavio Giupponi @ 31sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 36sec

- Luis Herrera, Stephen Roche @ 39sec

- Urs Zimmermann @ 42sec

- Maurizio Fondriest @ 44sec

- Piotr Ugrumov @ 53sec

Tuesday, May 30: Stage 10, Pesaro - Riccione 37 km individual time trial (cronometro)

- Lech Piasecki: 48min 26sec

- Erik Breukink @ 25sec

- Stephen Roche @ 33sec

- Rolf Sørensen @ 35sec

- Jesper Skibby s.t.

- Piotr Ugrumov @ 41sec

- Claude Criquielion @ 49sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 54sec

- Andrew Hampsten @ 55sec

- Moreno Argentin @ 57sec

GC after Stage 10:

- Erik Breukink: 45hr 8min 23sec

- Stephen Roche @ 46sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 1min 1sec

- Piotr Ugrumov @ 1min 5sec

- Flavio Giupponi @ 1min 23sec

- Maurizio Fondriest @ 1min 26sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 1min 46sec

- Claude Criquielion @ 1min 51sec

- Rolf Jaermann @ 2min 6sec

Wednesday, May 31: stage 11, Riccione - Mantova, 244 km

- Urs Freuler: 6hr 19min 28sec

- Mario Cipollini s.t.

- Adriano Baffi s.t.

- Paolo Rosola s.t.

- Fabiano Gambirasio s.t.

- Marcel Arntz s.t.

- Phil Anderson s.t.

- Peter Pieters s.t.

- Stefan Allocchio s.t.

- Rolf Sørensen s.t.

GC after Stage 11:

- Erik Breukink: 51hr 27min 59sec

- Stephen Roche @ 46sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 1min1sec

- Piotr Ugrumov @ 1min 5sec

- Flavio Giupponi @ 1min 23sec

- Maurizio Fondriest @ 1min 26sec

- Claude Criquielion @ 1min 43sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 1min 46sec

- Rolf Jaermann @ 1min 48sec

- Urs Zimmermann @ 2min 6sec

Thursday, June 1: Stage 12, Mantova - Mira, 148 km

- Mario Cipollini: 3hr 41min 4sec

- José Rodriguez Garcia s.t.

- Jean-Paul Van Poppel s.t.

- Silvio Martinello s.t.

- Adriano Baffi s.t.

- Paolo Rosola s.t.

- Stefano Allocchio s.t.

- Francesco Rossignoli s.t.

- Fabiano Fontanelli s.t.

- Marcel Arntz s.t.

GC after Stage 12:

- Erik Breukink: 55hr 9min 3sec

- Stephen Roche @ 46sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 1min 1sec

- Piotr Ugrumov @ 1min 5sec

- Flavio Giupponi @ 1min 23sec

- Maurizio Fondriest @ 1min 26sec

- Claude Criquielion @ 1min 43sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 1min 46sec

- Rolf Jaermann @ 1min 48sec

- Urs Zimmermann @ 2min 6sec

Friday, June 2: Stage 13, Padova - Tre Cime di Lavaredo, 207 km

![]() Major ascent: Tre Cime di Lavaredo

Major ascent: Tre Cime di Lavaredo

- Luis Herrera: 5hr 34min 41sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 1min 0sec

- Erik Breukink @ 1min 4sec

- Andrew Hampsten s.t.

- Franco Chioccioli @ 1min 10sec

- Roberto Conti s.t.

- Marco Giovannetti @ 1min 33sec

- Stephen Roche @ 1min 47sec

- Henry Cardenas @ 1min 58sec

- Jure Pavlic @ 2min 9sec

GC after Stage 13:

- Eric Breukink: 50hr 44min 45sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 53sec

- Stephen Roche @ 1min 32sec

- Luis Herrera @ 2min 15sec

- Piotr Ugrumov @ 2min 23sec

- Flavio Giupponi @ 2min 51sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 3min 4sec

- Claude Criquielion, Andrew Hampsten @ 3min 17sec

- Franco Chioccioli @ 3min 27sec

Saturday, June 3: Stage 14, Misurina - Corvara in Badia, 131 km

![]() Major ascents: Giau, Santa Lucia, Marmolada, Pordoi, Campolongo

Major ascents: Giau, Santa Lucia, Marmolada, Pordoi, Campolongo

- Flavio Giupponi: 4hr 7min 0sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 5sec

- Andrew Hampsten @ 8sec

- Marco Giovannetti @ 11sec

- Urs Zimmermann @ 14sec

- Franco Chioccioli @ 15sec

- Roberto Conti @ 1min 10sec

- Phil Anderson @ 2min 23sec

- Vladimir Poulnikov @ 3min 15sec

- Maurizio Rossi @ 3min 20sec

- Claude Criquielion s.t.

- Marino Lejarreta s.t.

- Maurizio Fondriest s.t.

- Moreno Argentin s.t.

- Stephen Roche s.t.

- Franco Vona @ 3min 31sec

- Roberto Tomasini @ 3min 53sec

- Eddy Schepers @ 3min 58sec

- Jesper Skibby @ 5min 40sec

- Erik Breukink @ 5min 51sec

GC after Stage 14:

- Laurent Fignon: 64hr 52min 36sec

- Flavio Giupponi @ 1min 50sec

- Andrew Hampsten @ 2min 31sec

- Franco Chioccioli @ 2min 51sec

- Urs Zimmermann @ 3min 3sec

- Marco Giovannetti @ 3min 43sec

- Stephen Roche @ 4min 1sec

- Erik Breukink @ 5min 0sec

- Roberto Conti @ 5min 7sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 5min 33sec

Sunday, June 4: Stage 15A, Corvara in Badia- Trento, 131 km

- Jean-Paul Van Poppel: 3hr 4min 26sec

- Alessio Di Basco s.t.

- Adriano Baffi s.t.

- Paul Popp s.t.

- Stephan Joho s.t.

- Urs Freuler s.t.

- Fabiano Fontanelli s.t.

- Andrei Tchmil s.t.

- Jürg Bruggman s.t.

- Luciano Boffo s.t.

GC after Stage 15A

- Laurent Fignon

Sunday, June 4: Stage 15B: Trento 83 km Girisprint

![]() Major ascent: Gardena

Major ascent: Gardena

- Lech Piasecki: 2hr 8min 21sec

- Luca Gelfi s.t.

- Francesco Rossignoli s.t.

- Jos Van Aert s.t.

- Piotr Ugrumov s.t.

- Maurizio Rossi s.t.

- John Carlsen s.t.

- Stefano Giuliani @ 21sec

- Adriano Baffi @ 2min 16sec

- Paul Popp s.t.

GC after Stage 15B:

- Laurent Fignon: 70hr 7min 39sec

- Flavio Giupponi @ 1min 50sec

- Andrew Hampsten @ 2min 31sec

- Franco Chioccioli @ 2min 51sec

- Urs Zimmermann @ 3min 3sec

- Marco Giovannetti @ 3min 43sec

- Stephen Roche @ 4min 1sec

- Erik Breukink @ 5min 0sec

- Roberto Conti @ 5min 25sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 5min 33sec

Monday, June 5: Stage 16: Trento - Santa Caterina di Valfurva, 205 km

Stage annulled because of bad weather

Tuesday, June 6: Stage 17, Santa Caterina Valfurva - Meda, 137 km

![]() Major ascent: Balisio

Major ascent: Balisio

- Phil Anderson: 3hr 44min 25sec

- Gianni Bugno @ 4sec

- Moreno Argentin s.t.

- Maurizio Fondriest s.t.

- Rolf Jaermann @ 6sec

- Silvio Martinello @ 15sec

- Stephan Joho s.t.

- Alessio Di Basco s.t.

- Paolo Cimini s.t.

- Fabiano Gambirasio s.t.

GC after Stage 17:

- Laurent Fignon: 73hr 52min 19sec

- Flavio Giupponi @ 1min 50sec

- Andrew Hampsten @ 2min 31sec

- Franco Chioccioli @ 2min 51sec

- Urs Zimmermann @ 3mn 3sec

- Marco Giovannetti @ 3min 43sec

- Stephen Roche @ 4min 1sec

- Erik Breukink @ 5min 0sec

- Roberto Conti @ 5min 25sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 5min 33sec

Wendesday, June 7: Stage 18, Mendrisio - Monte Generoso 11 km individual time trial (cronometro)

![]() Major ascent: Monte Generoso

Major ascent: Monte Generoso

- Luis Herrera: 28min 30sec

- Ivan Ivanov @ 19sec

- Andrew Hampsten @ 35sec

- Stephen Roche @ 35sec

- Erik Breukink @ 59sec

- Henry Cardenas @ 1min 2sec

- Vladimir Poulnikov @ 1min 3sec

- Flavio Giupponi @ 1min 11sec

- Urs Zimmermann s.t.

- Jesper Skibby @ 1min 18sec

- Jos Van Aert @ 1min 32sec

- Moreno Argentin @ 1min 37sec

- Franco Chioccioli s.t.

- Werner Stutz @ 1min 42sec

- Roberto Conti s.t.

- Marino Lejarreta @ 1min 44sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 1min 45sec

- Claude Criquielion s.t.

- Phil Anderson @ 1min 46sec

- Gianni Bugno @ 1min 53sec

GC after Stage 18:

- Laurent Fignon: 74hr 22min 34sec

- Flavio Giupponi @ 1min 15sec

- Andrew Hampsten @ 1min 21sec

- Urs Zimmermann @ 2min 29ec

- Franco Chioccioli @ 2min 43saec

- Stephen Roche @ 3min 9sec

- Erik Breukink @ 4min 14sec

- Marco Giovannetti @ 4min 38sec

- Roberto Conti @ 5min 22sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 5min 32sec

Thursday, June 8: Stage 19, Meda - Tortona, 198 km

- Jesper Skibby: 5hr 21min 36sec

- Massimo Ghirotto s.t.

- Franco Vona s.t.

- Piotr Ugrumov s.t.

- Jean-Paul Van Poppel @ 3sec

- Fabiano Fonanelli s.t.

- Paolo Cimini s.t.

- Stefano Zanatta s.t.

- Silvio Martinello s.t.

- Frank Hoste s.t.

GC after Stage 19:

- Laurent Fignon: 79hr 44min 13sec

- Flavio Giupponi @ 1min 15sec

- Andrew Hampsten @ 1min 21sec

- Urs Zimmermann @ 2min 29sec

- Franco Chioccioli @ 2min 43sec

- Stephen Roche @ 3min 9sec

- Erik Breukink @ 4min 14sec

- Marco Giovannetti @ 4min 38sec

- Roberto Conti @ 5min 22sec

- Marino Lejarretta @ 5min 32sec

Friday, June 9: Stage 20, Voghera - La Spezia, 220 km

![]() Major ascents: Penice, Mercatello, Tomario, Monte Vaca, Cento Croci

Major ascents: Penice, Mercatello, Tomario, Monte Vaca, Cento Croci

- Laurent Fignon: 6hr 10min 50sec

- Maurizio Fondriest s.t.

- Phil Anderson s.t.

- Flavio Giupponi s.t.

- Andrew Hampsten s.t.

- Erik Breukink s.t.

- Marino Lejarreta s.t.

- Stephen Roche s.t.

- Franco Chioccioli s.t.

- Paolo Rosola @ 8sec

GC after Stage 20:

- Laurent Fignon: 85hr 54min 53sec

- Flavio Giupponi @ 1min 26sec

- Anbdrew Hampsten @ 1min 31sec

- Urs Zimmermann @ 2min 47sec

- Franco Chioccioli @ 2min 53sec

- Stephen Roche @ 3min 19sec

- Erik Breukink @ 4min 24sec

- Marco Giovannetti @ 4min 46sec

- Roberto Conti @ 5min 40sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 5min 42sec

Saturday, June 10: Stage 21, La Spezia - Prato, 220 km

![]() Major ascents: Carpinelli, San Pellegrino, Abetone, Prunetta, Sammomme

Major ascents: Carpinelli, San Pellegrino, Abetone, Prunetta, Sammomme

- Gianni Bugno: 6hr 26min 50sec

- Claude Criquielion @ 46sec

- Laurent Fignon s.t.

- Flavio Giupponi s.t.

- Andrew Hampsten s.t.

- Erik Breukink s.t.

- Roberto Conti s.t.

- Marino Lejarreta s.t.

- Vladimir Poulnikov @ 1min 56sec

- José Salvador Sanchis s.t.

GC after Stage 21:

- Laurent Fignon: 92hr 22min 21sec

- Flavio Giupponi @ 1min 31sec

- Andrew Hampsten @ 1min 39sec

- Urs Zimmermann @ 4min 5sec

- Erik Breukink @ 4min 32sec

- Franco Chioccioli @ 5min 27sec

- Roberto Conti @ 5min 48sec

- Marino Lejarreta @ 5min 50sec

- Stephen Roche @ 5min 53sec

- Claude Criquielion @ 6min 6sec

Sunday, June 11: 22nd and Final Stage, Prato - Firenze 54 km individual time trial (cronometro)

- Lech Piasecki: 1hr 5min 34sec

- Greg LeMond @ 1min 3sec

- Flavio Giupponi @ 2min 5sec

- Vladimir Poulnikov @ 2min 15sec

- Laurent Fignon @ 2min 21sec

- Franco Chioccioli @ 2min 37sec

- Claude Criquielion @ 2min 49sec

- Erik Breukink @ 2min 51sec

- Czeslaw Lang @ 3min 4sec

- Maurizio Fondriest @ 3min 8sec

- Andrew Hampsten @ 3min 28sec

- Jesper Skibby @ 3min 31sec

The Story of the 1989 Giro d'Italia

This excerpt is from "The Story of the Giro d'Italia", Volume 2. If you enjoy it we hope you will consider purchasing the book in print, eBook or audiobook format. The Amazon link here will make the purchase easy.

Vincenzo Torriani, the grand old patrono of the Giro, was in failing health. Since 1975 he had been collaborating in running the Giro with Neapolitan lawyer Carmine Castellano, Castellano’s assistance being limited at first to handling the logistics of southern Giro stages. Castellano moved to Milan in the 1980s and became more deeply involved in organizing the race. Although Torriani was credited as co-director though 1992, Castellano actually took over running the race in 1989. In the later years of Torriani’s tenure, the Giro had opened up to become an important international race. Under Castellano, during the mid and late 1990s, the Giro would again become more of an Italian competition with fewer of the big international teams riding.

While Castellano was effectively in charge, Torriani hadn’t gone home just yet. When he phoned Laurent Fignon to entice him to ride the 1989 Giro, he told Fignon that it was, “one of the toughest in history”. The 1989 edition was indeed loaded with mountains, plus days of heavy roads and again was run without a rest day. World Road Champion Maurizio Fondriest said of the 1989 route, “With a course like this, Moser would never have won.”

After winning the Tour for a second time in 1984, Fignon was plagued by injuries and went into a deep decline. In 1987 he began to recover and in 1988, beating Fondriest in a two-up sprint, he won Milan–San Remo. In 1989 he astonished the cycling world with a second consecutive Milan–San Remo victory. His squad, however, was a shadow of the powerful team that had supported him in the early 1980s. He and his director Cyrille Guimard now owned the team and Fignon wrote that Guimard had become penny-wise and pound-foolish in his management which was reflected in the reduced quality of the team and support staff.

Torriani pulled out his checkbook and was able to induce Fignon to return to the Giro, but the Frenchman had no trust in Torriani, calling him the “same old bandit”.

Hampsten’s 7-Eleven team also returned, but their real goal was the Tour in July. Looking at the 3,418-kilometer, twenty-two stage race, Hampsten told Fignon that this race would not be won by the strongest man in the peloton, but by the smartest.

After his abortive 1988 attempt to ride the Giro, LeMond returned with a new team, ADR, a squad made largely of Classics riders and generally unsuited to Grand Tours. LeMond’s fitness for shorter races was tolerable: he came in fourth in the March two-day Critérium International. A three-week race would be an entirely different challenge.

After mass defections to other teams at the end of 1988 season, Alfa Lum found itself without riders. Maurizio Fondriest, for instance, moved from Alfa Lum to Del Tongo after winning the World Championship. In a perfect deus ex machina, a solution presented itself to the team management. The year before, the Soviet Union relaxed its ban on its riders turning pro. Alfa Lum pounced and signed up the cream of Russian cycling and instantly had a squad of fine riders. Alfa Lum’s entry into the 1989 Giro represents a giant step in the mondialization of professional cycling.

With a Sicilian start followed by stages taking the peloton first to the Dolomites and then the Alps before heading to a finish in Florence, 1989’s route left little of Italy unvisited.

After the three Sicilian stages, Contini led and his Malvor teammate Flavio Giupponi, fourth the year before, was sitting 15 seconds back, in third place. That third stage was a 32-kilometer team time trial and Fignon’s weak Super U squad was seventh, a minute and a half slower than winner Ariostea. Hampsten’s 7-Elevens were sent to the ground after a black cat picked a bad time to cross the road, making the team second to last, more than three minutes behind Ariostea.

The southern mainland stages, though hilly, produced no changes to the standings until the eighth stage which finished atop the Gran Sasso d’Italia. Marino Lejarreta, Erik Breukink and Colombian Luis Herrera, winner of the 1987 Vuelta, jetted off the front, gaining six seconds over the main body of contenders. Breukink was in pink by a single second over Acácio Da Silva.

The first individual time trial was at the Adriatic coastal town of Pesaro. Polish rider Lech Piasecki, a time trial specialist, won the 36.8-kilometer stage, but it was Breukink’s second place that really mattered. Fignon created no fear in his competitors (but apparently a little in his director Cyrille Guimard who expected better) with his eighth place, a half minute slower than Breukink. Fignon pronounced himself satisfied with the effort as it was his best time trial since 1986. Roche looked good with a third place that was only 8 seconds slower than the Dutchman’s.

After ten stages and with the Dolomites coming in just three days, the General Classification stood thus:

1. Erik Breukink

2. Stephen Roche @ 46 seconds

3. Laurent Fignon @ 1 minute 1 second

4. Piotr Ugrumov @ 1 minute 5 seconds

5. Flavio Giupponi @ 1 minute 23 seconds

Probably no one at the time was aware that history was being made, but the winner of the twelfth stage was 22-year-old neo-pro Mario Cipollini. That was the first stage win in a long and prolific career that would later see him try to break Alfredo Binda’s record of 41 Giro stage wins.

Mario Cipollini wins stage 21 in Mira

Leaving Padua, stage thirteen was a rainy trip to the top of Tre Cime di Lavaredo. At twenty kilometers to go, Herrera blasted off. Fignon said it was an almost exact replay of Herrera’s attack on l’Alpe d’Huez in the 1984 Tour de France and he got the same orders from Guimard, “Stay put!” Guimard surely feared Fignon’s blowing up while trying to chase one of the best specialist climbers ever. Herrera rocketed up the steep mountain, leaving a grumbling Fignon exactly 1 minute back with Breukink a further 4 seconds behind Fignon. The result of Herrera’s attack was Breukink’s remaining in pink with Fignon second at 53 seconds.

The tappone arrived and what a queen stage it was, with five major passes: Giau, Santa Lucia, Marmolada, Pordoi and the Campolongo. The finish was in Corvara, at the bottom of a short but twisty descent from the summit of the Campolongo. It was a horrible day in the mountains with dense and dangerous fog, snow, rain and temperatures near freezing. Fignon, who normally rode poorly in cold, wet weather, consented to having his entire body massaged with an extremely hot embrocation. The hot liniment put him in misery until the stage started, but he said he barely noticed the cold once he got going. He did several probing attacks and finally went hell-bent for leather on the Campolongo, taking a few riders with him, including stage winner Giupponi.

Breukink lost six minutes after going weak from hunger while Herrera crashed on the Marmolada. Fignon was the maglia rosa with Giupponi second at 1 minute 50 seconds and a now-interested-in-the-Giro Hampsten third, 2 minutes 31 seconds behind the Frenchman.

The terrible weather kept coming. The sixteenth stage was to have both the Tonale and the Gavia passes, but amid cries from the Italian press that Torriani was favoring Fignon by running the stage despite the bad weather, the stage was cancelled. Fignon was actually in trouble with an old shoulder injury making climbing in the cold almost impossible. But given his history of not only favoring Italians, but specific Italians, the accusation that Torriani was working to help a Frenchman win the Giro seemed strange. Furthermore, he had already confided to others that he hoped Giupponi would win.

For the moment, Mother Nature was on Giupponi’s side. The 10.7-kilometer timed hill climb up Monte Generoso, just over the border in Switzerland, was held under overcast skies. The day was cool enough to make riding up the mountain torture for Fignon. Herrera won the stage and all of Fignon’s competitors did well. Hampsten was third, only 35 seconds slower than the Colombian rocket. Roche and Giupponi were another half-minute behind. Fignon was seventeenth, 1 minute 45 seconds off Herrera’s pace.

Fignon was losing ground:

1. Laurent Fignon

2. Flavio Giupponi @ 1 minute 15 seconds

3. Andy Hampsten @ 1 minute 21 seconds

4. Urs Zimmermann @ 2 minutes 29 seconds

5. Franco Chioccioli @ 2 minutes 43 seconds

There were two hilly stages in Liguria and Tuscany and they might have spelled doom for Fignon, who was struggling. And then the worst possible thing for Giupponi happened, the weather turned warm and Fignon revived. Fignon mounted an attack on the Passo di Cento Croci, but had to slow because the lead motorbike wasn’t moving fast enough. He led out the sprint, won the stage, and took back 10 seconds.

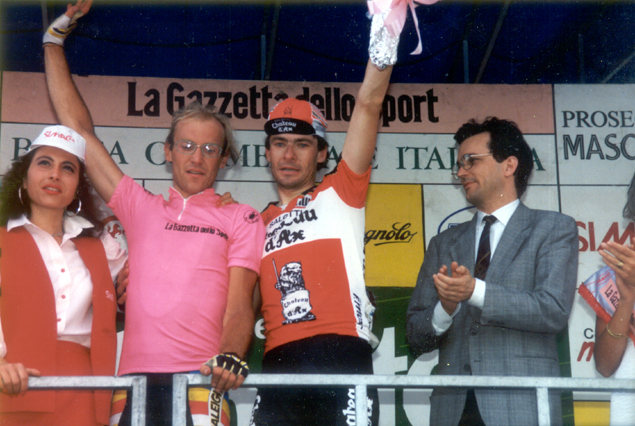

Laurent Fignon in pink with Gianni Bugno. Might be after stage 21

Another five rated climbs awaited the riders in the penultimate stage, and this time Fignon came close to losing the race. He was marking Giupponi and while following him on a descent, crashed with Belgian Claude Criquielion. By this point Fignon’s exhausted team was in tatters, leaving him without support when he needed it most. Fignon said Giupponi and Hampsten used the opportunity of the crash to attack. Fignon had no choice but to straighten his handlebars and go after them, which he did, catching them after a ten-kilometer chase. Showing that there was no damage from the crash and chase, Fignon won an intermediate sprint, snaffling up five precious bonus seconds.

Gianni Bugno then took off and no one saw him until the end of the stage, but Fignon was third at the finish in Prato for another 3-second bonus. Going into the final stage, a 53.8-kilometer time trial finishing in Florence, Fignon had a 1 minute 31 second lead over Giupponi, who was waging a never-say-die battle down to the last stage. The last two stages were so hard, fifteen riders who thought they were going to make it to the end either retired or were eliminated.

Lech Piasecki won the time trial, but second place was a shock. It was Greg LeMond, more than a minute ahead of third-place Giupponi. He had been suffering like a dog almost the entire Giro, sometimes barely making it to the stage finish before the time cut-offs. Desperate and miserable, he called his wife, Kathy, in Belgium and worried that he might not be able to continue. She told him to tough it out and then flew down to Italy to give him support. LeMond continued to flog himself and towards the end he finally began to find some of his old form.

And Fignon? He came in fifth, 16 seconds slower than Giupponi, good enough to clinch the Giro. He was only the third Frenchman to win the Giro, after Anquetil and Hinault, and as of this writing no Frenchman has won it since.

Merckx thought that without his big time loss in the stage three team time trial, Hampsten could have been the 1989 winner. He certainly would have been in the fight.

Laurent Fignon wins the 1989 Giro d'Italia

Final 1989 Giro d’Italia General Classification:

1. Laurent Fignon (Super U): 93 hours 30 minutes 16 seconds

2. Flavio Giupponi (Malvor-Sidi) @ 1 minute 15 seconds

3. Andy Hampsten (7-Eleven) @ 2 minutes 46 seconds

4. Erik Breukink (Panasonic) @ 5 minutes 2 seconds

5. Franco Chioccioli (Del Tongo) @ 5 minutes 43 seconds

Climbers’ Competition:

1. Luis Herrera (Café de Colombia): 70 points

2. Stefano Giuliani (Jolly Componibili): 38

3. Jure Pavlič (Carrera): 34

Points Competition:

1. Giovanni Fidanza (Chateau d’Ax-Salotti): 172 points

2. Laurent Fignon (Système U): 139

3. Erik Breukink (Panasonic): 128

Both LeMond and Fignon were back. Neither rider ever again found the extraordinary magic of the mid 1980s, but they were both so fabulously talented that even a diminished Fignon and LeMond were still better riders than anyone else.

After the Giro, while Fignon wanted to do nothing more than celebrate his Grand Tour comeback, a grim-faced Guimard insisted upon being the skunk at the picnic. Guimard was already planning their July Tour de France campaign and warned, “LeMond will be up there at the Tour.”

Fignon was dumbfounded that LeMond, who had been nowhere for three weeks of the Giro, had ended up taking second in the final time trial. About Guimard’s prophetic hand-wringing, Fignon wrote, “We all know what happened in July, 1989.” Not only did LeMond win the Tour that July, he became World Champion, outsprinting one of those Alfa Lum Russians, Dimitri Konyshev.

Spanish video of stage 13 (Padova - Tre Cime di Lavaredo), won by Luis Herrera

.