Fiorenzo Magni, a bridge between the legendary past and the modern era of cycling

By Valeria Paoletti and Bill McGann

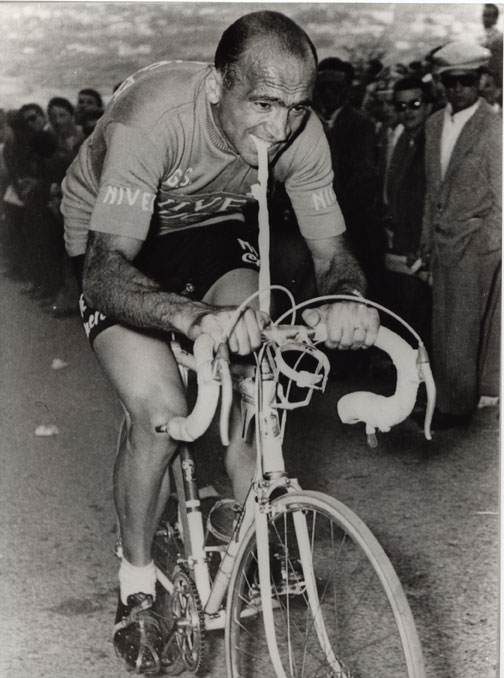

Battered and riding with a broken collarbone, Magni couldn't pull on the bars so he gripped a length of inner tube in his teeth in the 1956 Giro.

Bill and Carol McGann's book The Story of the Giro d'Italia, A Year-by-Year History of the Tour of Italy, Vol 1: 1909 - 1970 is available in print, Kindle eBook & audiobook versions. To get your copy, just click on the Amazon link on the right.

This interview was conducted in January, 2006. Fiorenzo Magni passed away October 19, 2012. We've left the introduction as we wrote it in 2006.

Modern cycling owes a lot to Fiorenzo Magni. This great man displayed a virtuosity and versatility that is part of a long-gone age in cycling. He is a three-time winner of both the Tour of Flanders and the Giro d'Italia. Remarkably, he walked out on the Tour de France while wearing the Yellow Jersey. This distinguished 86-year old man raced toe to toe with some of the greatest champions in the history of the sport: Coppi, Bartali, Geminiani, Bobet, Kubler and Koblet. But more than that, he changed the face of cycling by bringing sponsors to cycle racing from outside the bike trade.

His way of winning was almost Merckxian. He would attack, and if that assault didn't succeed he would attack again. He would continue to batter away until the peloton capitulated. His application of pure power yielded a list of wins that included, in addition to the races listed above, the Tour of Tuscany, the Baracchi Trophy, the Italian Championship, Milan-Turin and many others. As he notes in the interview below, his list of wins is particularly eloquent because he was riding during a golden age, when the men he had to beat were true giants. And by being able to beat them, he was a giant himself.

In reading the interview, one is struck by two things, and perhaps they are parts of his same big heart and character. First, he is fully accepting of the occasional bad cards fortune dealt him. He doesn't place blame, sound vindictive, nor does he express a desire for a replay. Second, he is very generous in his praise of others, even when their success consigned him to a lesser status in cycling's history.

Today Signor Magni is a busy man, running a large car dealership in Monza, a town just east of Milan, and is the president of the new cycling museum next to the Madonna del Ghisallo church near Como, Italy. When I met him on a snowy day in January, 2006, I was impressed by his sturdiness and by his strong personality. He introduced me to his wife and two daughters and invited me into his office where he keeps souvenirs of the fondest memories of his extraordinary career.

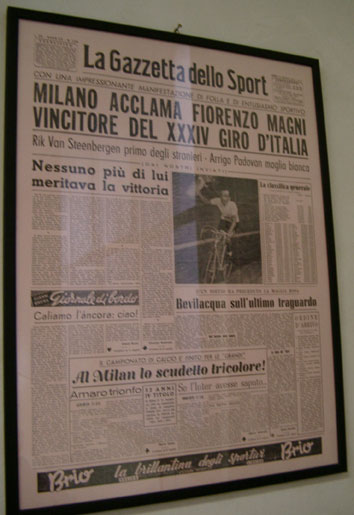

He showed me that cycling in the '50s had more fans than Soccer (the big sport in today's Italy) and how his Giro wins made a bigger splash in the newspapers' headlines than a soccer championship won by Milan or Juventus. Magni's career is so full of interesting details that I would have talked with him all day. His commitments to the soon-to-be-opened-museum gave us only one intense hour filled with his talk of a legendary era of cycling.

Valeria Paoletti: Before we go over your fantastic career and your memories of the great riders of the 1940s and 1950s I would like to talk about one of the most dramatic episodes in the history of cycling, your abandonment of the 1950 Tour de France. So that readers can understand the circumstances, let's step back just a bit. In the Spring of 1950 you had won the Tour of Flanders for the second year in a row as well as coming in 3rd in Paris-Roubaix and you came in 6th in the Giro. The Giro win included a solo victory in the 16th stage to Campobasso where you left Bartali, Kubler and Koblet behind. Would it be safe that when you started the Tour you were in superb form?

Fiorenzo Magni: Yes, safe enough. (Signor Magni smiles).

VP: There were two Italian teams at the Tour, the "A" team with Gino Bartali and a "B" team called the "Cadets". In which team you where riding? Was it agreed upon by the Italian team that you and the Cadets would all ride for Bartali, or you were given freedom race for your own victories?

FM: I was in the "A" team. We all rode for Bartali, but I was still given freedom. I have always been allowed the freedom to seek my own victories, except for the episode we are talking about.

VP: So let's go to that fateful stage 11 that went from Pau to St. Gaudens, crossing the Aubisque, Tourmalet and the Aspin. The Italians had so far won half the stages of that year's Tour. The French spectators watching the race along the mountain roads were in a bad, surly mood because the French had not won the Tour since 1947 and it looked like 1950 would not be a winning year for them either. At the top of the Aspin, at the front of the race, Bartali and Jean Robic crashed into a photographer. Robic remounted but Bartali was surrounded by angry spectators.

Bartali said he was kicked, punched and insulted. Can you tell us about this? Did you see this happen?

FM: I didn't see it, but many others, journalists and men from the other teams, saw what happened. And I believe what Bartali said.

VP: After the crowd was dispersed you and Bartali chased the field and caught the leaders, Bobet, Geminiani and Ockers, gaining back the 12 minutes you needed to take the overall lead from Bernard Gauthier. That day you got 9th in the stage but you were now in Yellow, ahead of Swiss rider Ferdy Kubler by two and a half minutes!

FM: That was quite something, wasn't it?

Fiorenzo Magni in his office in his car dealership. Valeria Paoletti photo

VP: But after the end of the stage Bartali, furious at his treatment at the hands of the crowd when he crashed, decided to quit the Tour and wanted both Italian squads to quit as well. What happened that evening?

FM: Bartali has always been a combative man, a true fighter. If he made this decision it was because it was no longer safe for the Italians to race. He was concerned about the situation.

VP: What was your relationship with Bartali like at that time?

FM: It was good, as it has always been. My abandonment was because of Bartali's decision, which was shared by the team manager Alfredo Binda and by the Italian Federation.

VP: What were your emotions? How did you feel about this, since you were the Yellow Jersey?

FM: Of course I felt bad about that but I believe that there are bigger things than a technical result, even one as important as winning the Tour de France.

VP: It's written that Binda gave you the freedom that evening to continue to ride the Tour for victory. True? Who made the decision then?

FM: Binda and the Italian Federation made the decision, on Bartali's suggestion.

VP: Did you feel that asking you to make this sacrifice was fair?

FM: I stuck to the rules and accepted their decision. In my life I have never pretended to have a role that was not mine. When they decided to withdraw I didn't pretend that I would go on in the race alone. This wouldn't be my style.

VP: The next morning at 8 you announced your withdrawal. Would you do it again today?

FM: I would do just the same thing today.

VP: Do you think you would have won the Tour?

FM: That's another story. Hindsight is easier than foresight! I think I had a good chance of winning. But I think that saying now that I would have won would not be very smart.

I didn't like renouncing the Yellow Jersey, of course! But I respected the rules and I am happy that I did it.

VP: And your relationship with Bartali remained good after all this, didn't it?

FM: Yes, absolutely.

VP: Let's step back to 1948 now. You won that Giro by a razor thin margin of 11 seconds. This would have been the first of 3 Giro victories and was accompanied by whistles and controversy.

FM: Yes, it was.

VP: Was this due to what happened during the 17th stage to Trento, with the Falzarego and Pordoi passes? Coppi won the stage and you took the Pink. But it seems that you were helped with some pushes by other riders. The judges handed you a penalty of 2 minutes. Coppi felt this was not enough and that the judges were helping you. He decided to quit with all his team (Bianchi). What happened?

FM: I don't think this was the reason why Coppi quit, I was Coppi's friend and, as with Bartali, nothing changed between us after this episode. I don't know why he withdrew.

VP: Why your victory was accompanied by whistles then?

FM: This is what happens in sport. That Giro's victory was a matter between me and Coppi and the spectators were torn between us. Coppi's tifosi [passionate fans] showed their letdown in Milan with their whistles.

VP: Why weren't you, the Giro winner, sent to the Tour de France in 1948?

FM: It was a technical choice made by the Italian Federation. Coppi didn't go either that year. We all were sent to the Tour the year after, in 1949.

VP: In 1949 you started that wonderful run of 3 straight Flanders victories. You prepared your bike and equipment for the Flanders race very carefully. I read that you used wooden rims, for their elasticity and strength, aged tubulars and foam-rubber all around the handle bar, true? More details?

FM: I had never been to Belgium, but I had heard and read in the newspapers that the roads were very tough, much harder than those of the Paris-Roubaix. Today the Tour of Flanders is not as tough as it was in my years.

So I thought it would a good idea to use wooden rims, which are less rigid than the traditional [aluminium] ones. It was hard to find those rims, but I found out that Clement produced them. Then I had a special kind of tubulars, larger and heavier than the normal ones, made. And I put foam-rubber all around the handle bar to cushion the blows.

I repeated all of these preparations the next year, in 1950, when I won again. I didn't use wooden rims in 1951.

VP: But you won all the same in 1951, for the third time! For a man of the Tuscan sun, Flanders seems a long, cold world away. Yet you thrived on these tough conditions. What was it about your body or mind that made you able to win this super tough-race?

FM: Thanks to Mother Nature, cold, windy, rainy or snowy days were music to my ears! It was the same with extreme heat! I had no problems in the torrid summer days.

In all three of my Tour of Flanders' victories I remember cold, terrible weather. I was in my element!

VP: Let's come to the 1949 Tour. You rode it on the second team of Italians, the Cadets. Did this team ride for it's own victory or in support of the Coppi/Bartali Italian team?

FM: We were free. But, as is fair, there was no rivalry between us. I was in good shape. I had skipped the Giro because of a sore throat and I was well prepared and fresh for that Tour.

VP: Yes, Stage 10 shows that! Jacques Marinelli was wearing theYellow Jersey. You broke away with 3 of the greatest rides of the era, Raymond Impanis, Edouard Fachleitner and Serafino Biagioni. How did it go?

FM: I beat the field into Pau by 20 minutes!! And I gained the Yellow Jersey. The next day was a tough day.

VP: Well, it was about as tough a day of racing as can be imagined with the Aubisque, Tourmalet, Aspin and Peyresourde. You lost 16 minutes. What happened to you? Robic won.

FM: I crashed during a descent and I was seriously hurt.

VP: You still had the lead, with Fachleitner a couple of minutes behind, and you kept the Yellow Jersey until the 16th stage (Allos, Vars, Izoard climbs). There, Coppi and Bartali won their famous victory, winning together. Did you expect to lose the Yellow there since Coppi was starting to demonstrate his strength?

FM: I expected that. After the crash my body weakened and I had been running a fever for many days. I should have quit but I didn't want to and in the end I finished in 6th in General Classification. I would have been on the podium if I had been in better health.

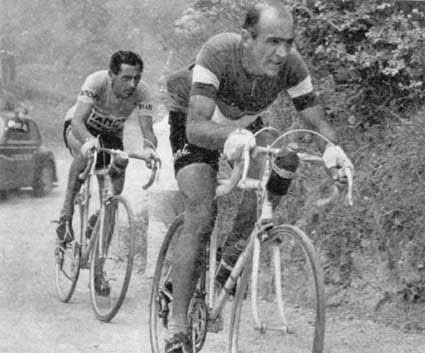

Magni, in the Italian Champion's jersey (which he won in '51, '53, '54), leads Fausto Coppi.

VP: How did wearing Yellow compare to wearing Pink? How did racing the Tour differ from racing the Giro?

FM: Wearing the Pink Jersey and racing in my country has always been very appealing to me. The appealing part of the Tour was its the great organization. Jean Gaudet was the greatest race organizer of all time. In each of the five and half Tours that I rode, I wore the Yellow Jersey and I was always in breakaways. So in some regards it was my race.

I can't say which one was better for me. I liked stage races very much. The longer I raced during the 3 weeks of the Tour, the better I felt.

VP: That was thanks to your distinctive physical strength and endurance.

FM: For sure. But there was more. During the weeks of a Grand Tour I lost weight and got down to 72-73 kilograms. That helped a lot in the climbs, which usually came in the third week of the Giro and the Tour. In the later years of my career I was always at the front of the race when we were in the mountains.

You may wonder why I didn't lose weight before the beginning of the Giro or Tour! It's not easy to lose weight and stay strong. You cannot just lose weight with a sauna for example.

VP: You are considered, with Alfredo Martini [former pro and former Italian national team coach], the "Sage of the Pedal". How is your relationship with him?

FM: I have known Alfredo Martini since 1936, when we started racing. He was my teammate at the time and then again some years later on the team Nivea. I rode my first race with him! He was first and I was second.

We have a fraternal friendship based on respect. We still call each other at least twice a week. In all these years we never had a misunderstanding.

VP: Tell me about the great tripod of Italian cycling, Fausto Coppi and Gino Bartali and you. Your feelings and experiences?

FM: Contrary to what one may think, I believe I had been very lucky to race with them, even if this meant winning far less often because they were so extraordinary. But in life defeats are more likely to happen than wins. Losing to Coppi and Bartali, and therefore congratulating them, is an experience that I am happy to have had and an experience that taught me a lot. I recognize and I have always recognized that they were. simply fantastic. They were born to climb as fast as they rode on the flats. My wife often came to races to be on the climbs to support me. Usually she first saw them passing by, riding like motorcycles, without even breaking a sweat. Then it was my turn and I was usually sweaty!

Coppi was my age and we were very close. Bartali was almost my fellow citizen [both being from nearby small cities in Tuscany] and we met very often. I have always admired them for what they could do and esteemed them for who they were. Not only they were champions, they were also great men. Why do you think we are still speaking about them? Because they made history.

VP: So you consider yourself lucky because racing with them you could be part of this history?

FM: Right! I would have won more without them but it wouldn't have been during a legendary cycling era!

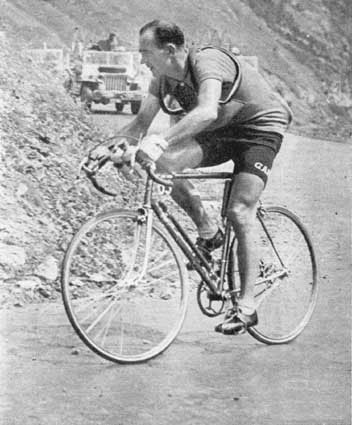

Magni, in an undated photo.

VP: One of the most beautiful episodes of this era happened during the Giro of 1955. This would have been your third Giro win when you were 35 years old. You wore Pink from the second stage through the ninth stage, then it was worn by Raphael Geminiani and then Gaston Nencini. During the penultimate stage (Trento-San Pellegrino), with Nencini in pink, you and Coppi went for an incredible breakaway of 170 km! This was one of those exploits that make history.

Nencini got a flat on a descent and you and Coppi attacked. It was like a 2-man time trial. Coppi won that stage and you took the Pink. Is it true that the Italian radios interrupted their programs to report this break?

FM: Yes, true. During the break I first saw signs saying "Viva Nencini!". Then people quickly changed them to "Viva Coppi!" and "Viva Magni!". After the radio had reported our break, with 80 km to go, the roads were overflowing with people. Thousands of people were waiting for this couple of "elderly" champions. When today I hear that a 35-year old athlete is considered old, I smile. It depends on the way you reach this age!

I think that my passion for cycling and my managerial spirit kept me young. In 1951 I started my first company, "Fiorenzo Magni srl", a motorcycle dealership. I trained in the morning and worked for my company in the afternoon. I could have continued racing for a many more years, but my managerial commitments started to keep me too busy. So, after 1956 I decided to quit racing, even though I had the strength to continue.

VP: Your physical and mental strength is not common.

FM: These virtues are not mine, they are my parents'. Human values come first. I have always put them before sport.

VP: Tell me about your 1954. You changed the face of cycling, bringing sponsors into cycling from outside the cycling world. I heard that the manager of your team, Pino Ganna (son of Luigi Ganna, the first Giro winner) told you in 1953 that he could not invest more money in cycling. Was he having a tough time?

FM: All the cycling companies, Atala, Bianchi, Legnano, Gloria were having a tough time. I was very friendly with the entire Ganna family but they had to stop running my team, so I was without a place. I started to think about a solution. I had some offers from other companies but they didn't fulfil my needs. I though I could find something better. I thought about this. First of all I needed the OK from the Italian Federation and that wasn't easy. I attended the meeting of the Federation in Turin, but I wasn't allowed to talk. Luckily I had some friends who pleaded my cause and the President saw in my idea an important chance for cycling.

VP: You ended up with the Nivea face cream company. Were they the first company you approached?

FM: I already had contacts with the men running Nivea, so I thought about this company first. I presented them with my program and they accepted.

VP: What were the details of the agreement? Do you remember the actual amount? Did they supply most of the money needed for the team or just part?

FM: They gave me 20 million Italian Lire [about 200.000 Euros or $260,000 in 2006 currency]. This money was for everything the team needed. At the end of the year there was not much left! But they were very generous and gave me a check for a similar amount of money plus they renewed our agreement for two more years.

VP: They liked the idea and they had a good return from all this, didn't they?

FM: They earned big profits from this operation. If you remember that cycling was more popular than soccer and that I was the first to do this then you can understand the success of this action. Nivea always thanked me for my idea, even years later. This was the beginning of the salvation of cycling.

VP: Did you know that many French think Géminiani's St-Raphaël team was the first extra-sportif sponsored team even if Geminiani did it in 1962?

FM: I consider France a country with a big sports tradition and culture. I didn't know that. Well, what can I say? They should know that I did it 10 years before!

VP: What was the reaction of the other sponsors? I heard they didn’t like your idea at all. The French tried to ban your team from riding the Paris-Roubaix. Is it true that you could take part in the race only thanks to Fausto Coppi's intervention?

FM: Yes, they didn't want me to wear my Nivea Jersey and told me that I could race only if I wore the Italian Champion's Jersey. But Coppi said he would not race without my wearing the Nivea jersey that day. He understood this was the future of cycling. The French didn't want to lose Coppi so I raced with my jersey that day and every other day!

The 3 great men. Left to right: Fiorenzo Magni, Gino Bartali, Fausto Coppi.

VP: What is your fondest memory? What is what you consider your greatest win?

FM: I consider my greatest win my second place in GC at the Giro of 1956, my last year as a pro.

VP: You were a very brave second in that incredible Giro. Tell us what happened.

FM: During stage 12, from Grosseto to Livorno, I crashed on the descent out of Volterra and broke my left collarbone. At the hospital they said I should put on a plaster cast and quit. But I didn't want to. Since the next day was a rest day, I told the doctor to do nothing and that we should wait and see. The day after I asked the doctor to put on an elastic bandage instead of a cast because I wanted to try to ride the following stage, Livorno to Lucca. It worked! I wasn't among the first riders but I finished.

VP: There is the famous picture of your riding holding a piece of inner tube in your mouth during the 13th stage, the individual time trial of San Luca. Can you explain?

FM: Just before the stage started I tried to ride my bike on a climb and I noticed I couldn't use the muscles of my left arm to pull on the handle bar very hard. So my mechanic, Faliero Masi, the best mechanic of all time, cut a piece of inner tube and suggested I pull it with my mouth. That was a great idea!

VP: Then, during stage 16, from Bologna to Rapallo, through the Apennines, you crashed again and broke your humerus.

FM: Yes, I didnt have enough strength in my left arm and I crashed after hitting a ditch by the road. I fell on my already broken bone and fainted from the pain. The ambulance came to bring me to the hospital. In the ambulance they gave me water and I got back on my feet. When I realized that I was being taken to the hospital I screamed and told the driver to stop. I didn't want to abandon the Giro!

I mounted my bike again and restarted pedaling. The peloton had waited for me, so I arrived in Rapallo in a relatively good position. I had no idea of how serious my condition was, I just knew that I was in a lot of pain but I didn't want to have X-rays that evening. During the days that followed I could hold my own.

VP: You were even able to ride the Stelvio Pass (Stage 19)!

FM: Yes, there I didn't have problems on the climb, but the descent was hard. On the climb I could go up at my own speed. At that point my aim was just to finish the Giro, not to win it of course. I didn't want to abandon the Giro in the year of my retirement.

VP: Why did you have problems on the descent?

FM: Because I could not brake with my left hand and I skidded. That was tough!

La Gazzetta dello Sport hails Magni's second of 3 Giro wins in 1951.

VP: Then there was Stage 20 from Merano to Trento, over the Costalunga, Rolle, Brocon and Bondone climbs. Pasquale Fornara was the Pink Jersey. That day 60 people abandoned! What happened?

FM: It snowed the whole day and it was very cold, I had not noticed how much. Along the way I saw many bikes parked next to bars and I asked what was going on. They told me that most of the peloton froze and had to quit. Then, before reaching Trento I saw the Pink Jersey quitting too! "What?? Am I seeing things?" I wondered.

If I were the Pink Jersey I would have continued, even if I had to walk, but I would never abandon!

VP: What happened next?

FM: When we were in Trento my team car came up to me and said I was third. "Third?!", I wondered again. I was third that day and became second in the GC.

VP: Gaul won that stage and went from 16 minutes behind to winning the 1956 Giro.

FM: Actually, I thought about attacking Charly Gaul in the following stages and trying to win my fourth Giro. I tried attacking him a couple of times during the last two stages, but he was too strong.

The day after the end of the Giro I went to an institute that specialized in bone injuries. And they gave me a dressing-down! They said I had two fractures - I thought I had only one - and forced me to put a plaster cast on.

The next day I went to my machine shop and asked my mechanic to cut the plaster cast away with the special scissors he used for sheet metal. This way I could start training again. Well, my shoulder is a little crooked now, but that's that. Can you notice that??

VP: No, no, I can't! (Signor Magni laughs). After your retirement in 1956 you started a successful career as manager. Tell me about it.

FM: To begin with I was coach of the Italian Team at the World Championships in '65 and '66, then I was President of the Association of the Riders (Associazione dei Corridori) and of the Cycling League. Then, and this was very gratifying for me, I was President of the "Azzurri d'Italia" for many years. That means president of all the athletes, from all the sports, wearing the blue jersey of the Italian National Team. I left all these roles after some time, even if I enjoyed them, when I felt it was time to change. I needed to do other things and give more time to my family.

VP: You are now President of the "Fondazione Museo del Ciclismo". This is an association promoting the building of a new museum of cycling next to the famous Sanctuary of the "Madonna del Ghisallo" (Como). The "Madonna del Ghisallo" is considered the patron saint of cyclists and its Sanctuary contains trophies, bikes, jersey and photos from legendary champions. There are so many donations of cycling memorabilia that the little church can't contain them anymore and you are giving those mementos a real museum. When I visited the Sanctuary last year the new building was almost ready. What is the status now? Tell us about this enterprise. Will it be the biggest cycling museum in the World?

FM: This museum is dedicated to cycling, not to one single champion. It will contain the trophies and the mementos of all the greatest riders, starting from 1909, the year of the first Giro d'Italia. But even the riders who didn't have much luck in their careers will be remembered. Then there will be a section for the teams and a section dedicated to the best sport journalists.

I owe a lot to the Regione Lombardia and to many sponsors, such as Mapei and Fassa Bortolo, who helped me in many ways in this big project. I received donations from individuals, and even from other countries like the U.S. I am very grateful to all of them.

VP: How did you get this idea?

FM: I thought that the future generations should have a memento of what cycling was and is today. The museum will have souvenirs such as the very first Yellow Jersey and Pink Jersey. Andrea Bartali, son of Gino Bartali, will donate it. Then there will be a database, accessible to everybody, containing information about all the riders. The museum and the sanctuary of the "Madonna del Ghisallo" are on the Pass of Magreglio, a spectacular spot very popular among cyclists. So I am also working on having a Giro stage passing by the Magreglio Pass. This museum will be the place for all people who love cycling.

VP: Signor Magni offered me a coffee and proudly showed me pictures of his nephews. It was nice to exchange a few words with his wife, who was next to him during all those incredible exploits. It was snowing hard outside and I would have talked with them longer, but Mr. Magni had four more meetings that day! He confessed that he has fun when he is busy with many different things and I am sure that this is the secret of this amazing man.