Jacques Anquetil

By Owen Mulholland

Owen Mulholland's other story on Jacques Anquetil is posted here.

Bill & Carol McGann's book The Story of the Tour de France, Vol 1: 1903 - 1975 is available as an audiobook here. For the print and Kindle eBook versions, just click on the Amazon link on the right.

Owen Mulholland writes:

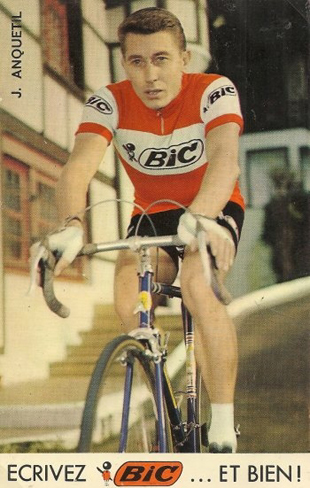

The sight of Jacques Anquetil on a bicycle gives credence to an idea we Americans find unpalatable, that of a natural aristocracy. From the first day he seriously straddled a top tube, "Anq" had a sense or perfection most riders spend a lifetime searching for. Between 1950, when he rode his first race, and nineteen years later, when he retired, Anquetil had countless frames underneath him, yet that indefinable poise was always there.

The look was that of a greyhound. His arms and legs were extended more than was customary in his era of pounded post World War Two roads. And the toes pointed down. Just a few years before, riders had prided their ankling motion, but Jacques was the first of the big gear school. His smooth power dictated his entire approach to the sport. Hands resting serenely on his thin Mafac brake levers, the sensation from Quincampoix, Normandy, appeared to cruise while others wriggled in desperate attempts to keep up.

Jacques Anquetil in 1967

At the normally tender age of nineteen (1953), Jacques plunged into the professional side of the sport, convinced that this daring move would be more financially rewarding than strawberry picking. He wasn't wrong.

His first major race in the colors of La Perle Bicycles was the Grand Prix des Nations, the most famous and difficult of all time trials. At 140 kms. it was nearly twice the distance of the current version. Undaunted, Anq led from start to finish. The legend had begun.

That legend came to be composed mostly of magnificent solo rides against the clock and tour victories. Just as significantly, with but two exceptions, there were no great one day road race (classic) wins on that list. Jacques never concealed his disdain for road races. He feared the danger of rubbing elbows in the peletons and the explosive jumps of his rivals. It was all so, well, plebian.

His natural self-assurance would have indicated a birth at Versailles two centuries earlier. Just after Jacques' first win in the Nations, Louison Bobet (top French star of the day) came over to congratulate him. "A great ride. I'm pleased to meet you." Bobet said as he extended his hand.

"But we already know each other." Anquetil responded. "I beat you in a pursuit race last Sunday.''

Onlookers choked, but the two "grands" understood. Anquetil had meant no offense and Bobet took none.

In November, the Normand drove down to Italy for the Tropheo Baracchi race. En route he visited the most famous rider of that era, Fausto Coppi. Coppi was more than hospitable. He revealed his entire approach which emphasized a rigorous discipline. Fausto concluded their meeting by inviting Anquetil to live with him. Who wouldn't have been blown away? Anquetil was certainly touched, but making his excuses he left. Even as he walked to the car he mused, "I know I have to go to the front alone."

In a career that included victories in all three major national tours (France-5, Italy-2, Spain-1), nine Grand Prix des Nations, the hour record (twice, eleven years apart), and almost countless other events it's difficult to choose among the great moments.

For much of his career he won tours in a "quiet" way that the public didn't appreciate. For weeks he could stay close to his enemies, and then attack in a time trial. His method of "just enough" didn't appease those who craved bold moves. When Anquetil was his most dominant, leading the 1961 Tour de France from first day to last, he was accused of being the rider "whom no one could drop, but who could drop no one."

The Tour organizers, ever sensitive to criticism, progressively reduced the time trials and piled on the mountains. By 1963 Jacques knew he'd have to alter his plans. After the Pyrenees and two time trials, Jacques trailed the great Spanish climber, Federico Bahamontes. With the Alps yet to cone Anquetilists worried about their man. The biggest Alpine stage into Chamonix featured a new climb, the steep, rocky Col de Forclaz. This came after two other first category monsters. Anq and Baha mounted 42X26, gears normally seen on tourist bikes.

When the "Eagle of Toledo" made his expected attack only one man could hold him. It was the new Jacques Anquetil, riding as he knew he must. Jacques was so in control that he didn't attempt to respond to ever acceleration by the Spaniard. Instead, Anq maintained a steady rhythm that pulled Baha back as surely as a fish on a line. At the summit Anquetil was actually setting the pace. He knew he had the stage, and race, in the bag. He also had a new popularity.

Just one little problem. He had made the climb on his light time trial bike which was considered too fragile for the wild gravel-strewn descent. But Tour rules didn't allow a bike change for any reason other than mechanical breakdown. Anquetil's crafty manager, Raphael Geminiani, had a solution.

With the top in sight Jacques gave Gem the eye. Jacques yelled, "My derailleur!"

"Shit!" responded Geminiani loud enough for a passing race official to hear. "He's broken his derailleur!"

The mechanic leaped from the car, spare bike in hand. As he handed the new bike to Jacques, the mechanic produced a pair of wire cutters and snipped the cable on the side away from the judge. The judge saw nothing and Anquetil was pushed on his way. A perfect example of Tour founder, Henri Degranges' motto for success, "Tete et Jambes" ("Head and Legs").

From that day, Anquetil, paired with Geminiani, went on to ever more creative wins. In 1964 he became the only rider other than Fausto Coppi to win the Giro d'Italia and Tour de France in the same year. In 1965 he won the Dauphiné-Liberé, a tough week long stage race, jetted across France the evening of the last day, slept for four hours, and then pedaled off into the four a.m. darkness and rain of the 365 mile long Bordeaux-Paris race. You have to ask? Anquetil won of course.

Jacques rode his last major tour in 1967. It was the Giro d'Italia, and he only finished in third, victim of the hot young Italian, Felice Gimondi. Down in seventh place was another star of the new generation, Eddy Merckx.

Merckx and Anquetil each was the master of a generation. Merckx, of course, tried to win everything all the time. That was hardly Jacques' mentality. One quality they did share was the ability to suffer on their rare "off" days. It's easy to win when you feel great and everyone has a complex about your strength. But to persevere when the myth is shattered, when the champion is exposed as mortal after all-then a real measure of the man is possible.

Anquetil had a particularly low point at the end of 1962. His training had tapered off after the Tour and by the end of October he was far from his best form. But the contract for the Tropheo Baracchi had been signed; there was no ducking the obligation. The Tropheo is a two man time trial and in eight attempts Jacques had never won it. Something about the change in tempo while alternating the lead was unsettling to him.

His partner was Rudi Altig, a formidable rider from Germany. (For example, Altig beat Eddy Merckx in the opening time trial of the 1969 Tour de France.) Rudi set the pace from the start-just under 47 kph! The closest team was over rive minutes in arrears, but the young German didn't back off for a second.

After 70 kms. Jacques couldn't take it anymore. It took all his enormous talent just to hold Rudi's wheel. Forty kms, almost an hour of purgatory remained. For twenty kms. Rudi continued at his infernal pace. Then, suddenly, he sensed Jacques slipping out of his draft. Altig pulled to the side, let Jacques ride past, and then Rudi sprinted up to Jacques, pushed him back up to speed (all this on 52X13) before resuming his place at the front, all the while shouting encouragement. The more Altig sensed that victory might be lost the more crazed he became. He pushed Anquetil dozens of time. It was truly superhuman.

Anquetil never dreamed of quitting. "I was in a fog." he admitted later. "I could only distinguish vague forms. All I cared about was getting the maximum protection on Altig's wheel."

At the entrance to the velodrome for the finish it was necessary to enter the track through a tunnel under the stands and then turn onto the track. Jacques never made the turn. He plowed straight into a telephone pole. Fortunately, times were taken at the track entrance. The watch showed that Altig-Anquetil had won comfortably, but what Jacques won that day, not to mention his fans and adversaries, was an appreciation of his full capabilities.