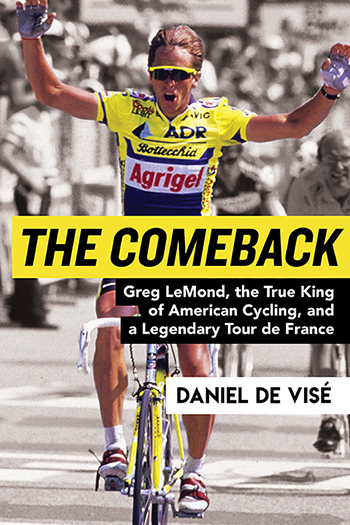

THE COMEBACK:

Greg LeMond, The True King of American Cycling, and a Legendary Tour de France

By Daniel de Visé

Book review, excerpt & author interview

Back to Riders Histories index page | Our main Greg LeMond page

There's a lot here.

- Review: First off, Peter Joffre Nye was kind enough to send me his review of Daniel de Visé's book on Greg LeMond and the 1989 Tour de France.

- Excerpt: After that review, on this same page, is a an excerpt from The Comeback

- Interview: And just below that, Mr. Nye interviews Daniel de Visé

Le Mond’s Career Gets Nuanced Perspective

By Peter Joffre Nye

THE COMEBACK: Greg LeMond, The True King of American Cycling, and a Legendary Tour de France

By Daniel de Visé

362 pp. Illustrated. Grove Atlantic.

Dan de Visé in The Comeback: Greg LeMond, the True King of American Cycling, and a Legendary Tour de France, presents a fresh perspective on one of the greatest contests in modern cycling—the 1989 Tour de France.

Today many recall how after three weeks of racing around the inside of France, the size of Texas, LeMond had ranked second overall, 50 seconds behind France’s two-time winner Laurent Fignon. Instead of the traditional pack finish up the Champs-Élysées in Paris, Fignon’s home town, Tour organizers held a 24.5-kilometer individual time trial, from Versailles to Paris. The betting crowd considered Fignon’s lead insurmountable. They favored him by a margin of 15 to 2 to win his third Tour.

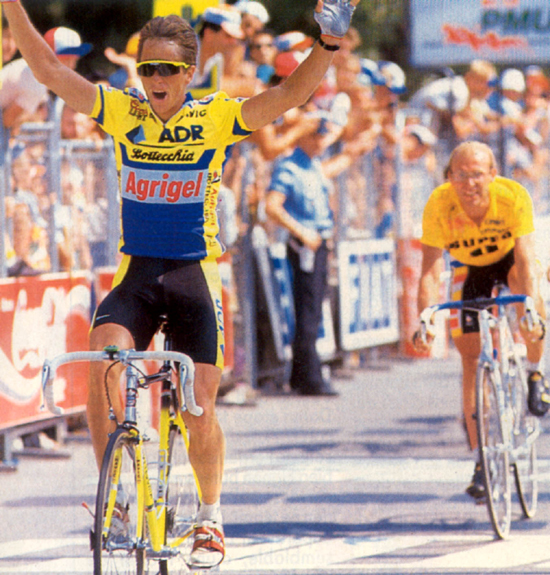

Greg LeMond finishes ahead of Laurent Fignon in stage 18 of the 1989 Tour de France

De Visé, a former newspaper reporter for the Washington Post and Miami Herald, frames The Comeback around the epic battle between LeMond and Fignon. Their clash in cycling’s flagship race, the crown jewel of the sport, deserves revisiting. Especially since LeMond had won the 1986 Tour, the first non-European ever to claim victory, only to nearly die the following spring in an accidental shotgun shooting while quail hunting in northern California.

De Visé points out the graveness of LeMond’s wounds. Surgeons cut him open from the sternum to below the belt line to remove lead shotgun pellets the size of bbs. He still has 30 pellets in his torso, including two in the lining of his heart.

In the legendary time trial that concluded the 1989 Tour de France, LeMond rode faster than Fignon and won overall by eight seconds, equivalent to less than 100 meters over 3,285 kilometers. His victory is still Le Tour’s closest in 115-year history.

De Visé provides a fuller, more complex portrait of LeMond, now fifty-seven, than anything previously published. He also informs readers about the enigmatic, contrary, and similarly talented Fignon. De Visé conducted a fulsome battery of interviews with Greg and Kathy LeMond, Greg’s father Bob, friends, former teammates, Fignon’s widow, and others.

LeMond had entered cycling as a novice junior in Reno, Nevada when the U.S. Cycling Federation was a startup. He competed on a USCF national team in France where he came to the attention of Frenchman Cyrille Guimard, the maverick director of the Renault-Gitane professional team. In an unusual yet brilliant hire, Guimard recruited him for the 1981 season.

The Comeback chronicles LeMond’s coming of age as a neo pro, an ocean away from his homeland and the American media. LeMond joined Fignon as support riders for team captain Bernard Hinault, on his way to capturing Le Tour five times to tie earlier legends Eddie Merckx and Jacques Anquetil.

Hinault comes off as a complicated farm boy from northwest France. His idea of a good time was showing up with a case of wine under each arm to a training camp and helping teammates drink every bottle as part of their bonding. When LeMond received a Renault car for personal use that came with a flat tire, he didn’t know what to do. Hinault cheerfully rolled up his shirt sleeves and changed the tire. This is the same Hinault who later betrayed LeMond in the 1986 Tour by racing against him until LeMond outclassed him—itself an achievement.

LeMond won a third Tour in 1990. Along the way he upended staid European cycling traditions. He played golf. He liked hunting. He ate ice cream. He replaced jerseys with 12-inch zippers for ones with 18-inch zippers to ride with more ventilation up mountains. LeMond alone possessed the clout to become the first million-dollar cyclist.

De Visé acknowledges that while LeMond is typically portrayed as a hugely talented athlete, endowed with an uncanny insight into strategy, he also is cursed with forgetfulness and the attention span of a gnat.

As Lance Armstrong soared to global stardom in 1999 through seven Tour wins, he overshadowed LeMond. But when Armstrong became ensnared in lying, cheating, and doping scandals, LeMond emerged as America’s only true Tour winner.

The Comeback lays out the withering barrage of obstacles and betrayals LeMond faced. Such struggles and triumphs beg to be turned into a ten-part mini-series.

De Visé never pinned on a competitor’s number. But he grew up watching pelotons in which his father, Pierre, raced. De Visé writes with perfect pitch. His book joins a growing cannon of American cycling lit.

(Peter Joffre Nye is author of The Fast Times of Albert Champion: From Record-Setting Racer to Dashing Tycoon, An Untold Story of Speed, Success, and Betrayal.)

Excerpt from The Comeback

LeMonster

AMERICAN BICYCLE RACES OF THE 1970s resembled Grateful Dead concerts, albeit on a smaller stage. A fleet of station wagons and Econoline vans would arrive in some remote locale by dead of night. As dawn broke, the vans would disgorge their contents, and the lot would fill with frames, wheels, pumps, coolers, and lawn chairs, with riders, parents, siblings, and fans.

Decades earlier, bicycle races could bring entire cities to a halt. Now they existed at society’s fringe, relegated to empty industrial parks and shuttered downtowns and underused recreation areas on sleepy Sunday mornings. Race organizers often lacked permits, and the highway patrol would occasionally sweep in to shut them down.

“It was kind of an underground sport,” recalled Roland Della Santa, a master bicycle craftsman from Reno, Nevada. “It was totally off the grid.”

In March 1976, a fellow Nevadan named Greg LeMond journeyed to California to enter his first proper bicycle race. Greg was fourteen. He had competed against other cyclists just once before, a few weeks earlier. That had been an informal club contest, pitting the promising teen against members of the venerable Reno Wheelmen, some of the most serious amateur racers in Nevada. The race had comprised four laps around a seven-mile loop that passed right by the LeMond home, twenty-eight miles in all. At the finish, Greg had taken second place.

And so, the LeMonds piled into father Bob LeMond’s forest-green Volkswagen bus and drove two hours to Sacramento, where, on March 6, Greg rode in his first amateur cycling contest, the William Land Park Criterium.

Bob & Greg LeMond

As a Nevadan, Greg would race in an amateur circuit that encompassed both his state and northern California. That would prove both a blessing and a curse; most races lay hundreds of miles away, but Greg would face some of the best cyclists in the nation.

American amateur cyclists raced in age categories. Preteens rode as “midgets.” Greg, a relative latecomer, rode as an intermediate, with other boys of thirteen, fourteen and fifteen. His first race spanned ten miles. At the starting gun, Greg shot forth from the pack, leaving most of the other boys far behind. Soon, only three others remained in the lead group. Though Greg had never really raced before, he immediately asserted himself as the leader, “barking commands at us to rotate through and keep the speed up,” one of the startled teens recounted.

Greg easily took the final sprint. He had won his first race. Greg was overjoyed.

The LeMonds drove another hundred miles to Dublin, east of San Francisco. There, on March 7, Greg entered his second cycling contest, the Tassajara Road Race. The course of twenty-five miles pitted him against several other boys of various shapes and sizes. One was another fourteen-year-old, Kent Gordis. Like Greg, Kent was new to bicycle racing. Unlike Greg, Kent had trained with the great George Mount.

Born one day before Greg, Kent had grown up in Switzerland, where his father worked on one of the first corporate computer systems. When Kent’s parents divorced, his mother decamped to Berkeley. Kent joined the Velo Club Berkeley, one of the nation’s preeminent amateur clubs, founded in the 1950s. Its star was George Mount, a powerful cyclist who would place a remarkable sixth in the 1976 Olympic road race in Montreal.

The club hosted weekly training rides; when Kent would reach the top of a particularly grueling climb, he sometimes found himself alone with George.

That spring weekend in Tassajara, Kent had entered his first race, emboldened by his training rides. Surely, he thought, no one in this ragtag bunch could beat him, least of all the kid in the Big Bird outfit.

Greg’s unruly golden locks spilled out from beneath a thick black leather Kucharik helmet, an apparatus whose curved temple protectors made the young cyclist look like an old-time football player. “And he had this goofy, goofy smile on his face,” Kent recalled.

But then the gun sounded, and Greg was gone, a canary-yellow blur receding into the distance. Kent could barely hold his wheel. At the end of the twenty-five miles, Greg held the lead, and Kent sat several lengths behind him, huffing and puffing in second place. The third-place finisher was ten minutes down the road.

Wiping the sweat from his brow, Kent asked the canary boy, “What’s your name?”

“Greg. Greg LeMond.”

“Hmm,” Kent panted. “Well, you’re not bad.”

Kent began to visit Greg at his Nevada home, and Greg visited Kent in Berkeley, and together they made pilgrimages to the French bookstore in San Francisco. Though he was no older than Greg, Kent possessed vital knowledge on the alien universe of professional cycling. Kent knew some French, and he would translate for Greg as they paged through yellowing copies of imported cycling magazines.

Around his fifteenth birthday, Greg would qualify for the national cycling championships with a victory in San José, California. He was one of four men and boys from Reno to earn a spot in the nationals. The others included Greg’s father, Bob LeMond, who had very nearly won the senior men’s road race. There could be no further doubt about the source of Greg’s gift.

The relationship between a precocious child athlete and the child’s parents can be complex. Parents sacrifice weekends and evenings to shuttle their children to events and practices. They live vicariously through the child’s feats. Sometimes, the child’s career becomes the parent’s life.

It was not so for the LeMonds, because Bob raced right alongside his son. On the Nevada-California cycling circuit, many racers knew of Bob’s exploits before they became aware of Greg. Within a year after he started cycling, Bob raced as a Category I senior, “competitive on a national level, which is unheard-of,” recalled Roland Della Santa, who had befriended the LeMonds and encouraged Greg.

In 1978, at thirty-eight, Bob would take fifth place in the Red Zinger Bicycle Classic, the nation’s premier multistage men’s bicycle race. Bob coached his son, but Greg also coached his father, dispensing endless advice on the topography of the course and the strengths and weaknesses of his rivals as the elder LeMond prepared for a race.

Greg had inherited his mighty heart from his father—and from his mother. At the cellular level, Greg’s cardiovascular power came from his mitochondria, the tiny furnaces that convert oxygen and nutrients into energy. Mitochondria concentrate in skeletal muscle and in the heart, making up about one-third of its volume. They adapt and multiply to meet the body’s needs. Thus, through genetics or conditioning or both, elite athletes have more mitochondria, and more productive mitochondria, than other people. Greg, who could consume more oxygen for energy than any other cyclist on the West Coast, had more mitochondria—or “better” mitochondria—than other elite athletes.

And mitochondria are passed down by the mother.

Bertha LeMond also bequeathed to Greg her toughness; she removed cookie sheets from the oven with her bare hands. Greg received those considerable assets along with some liabilities, including chronic allergies and feet of such divergent sizes that he often purchased unmatched shoes. Greg also had a bad kidney; it failed following a severe infection at age eleven, costing Greg months of missed school, his only real health scare in childhood.

For all his promise, Greg was not generally regarded as the most gifted athlete in the LeMond family. That distinction went to Karen, his younger sister. Karen LeMond took ballet and dance classes from first grade and soon became deeply immersed in gymnastics.

Throughout their teen years, Karen and Greg would crisscross the nation from one competition to the next. Their parents secured permission for both children to leave school early every day to train. At the dinner table, the two siblings would argue about whose sport was harder.

“It was my life for . . . it felt like my whole childhood,” Karen recalled. “I got out of school at noon. Someone would come and pick me up. [We] would go over to the gym, and I would work out until my parents picked me up at seven.”

Bertha generally traveled with Karen, Bob with Greg, until the children were old enough to drive themselves. While they offered full-throated encouragement and endless support, Bob and Bertha were not the stereotypically overbearing sports parents. The obsessive drive that compelled Greg and Karen to spend hours a day in training and competition seemed to have arisen spontaneously in the LeMond children.

“I loved it. I loved it,” Karen remembered. “I kept getting injured, and I would still go to the gym, six, seven hours. I had a brace on my knee for almost a year. And I went to the gym every day. My parents begged me to quit, because they knew I was injured. But it just wasn’t in me.”

Karen competed for five years, won an amateur national championship and enjoyed a growing reputation until 1980, when an accumulation of injuries forced her to stop.

With three LeMonds engaged in a more-or-less daily regimen of training and competition, older sister Kathy and mother Bertha were compelled to take up equally strenuous supporting roles. The family often traveled to weekend competitions together. Bertha preferred to dwell in the background, doing whatever was asked of her, never complaining.

“My dad, he’s a hiker,” Kathy explained. “My mom would sit for two or three days in a trailer park and read while my dad went hiking. She would sit and wait for him.”

When Greg grew inquisitive about cycling attire and equipment, his older sister shepherded him to fabric stores, helped him pick out thin nylon material, and stitched together custom jerseys for her brother. She learned to sew hook-and-loop fabric around Greg’s shoes so that he could strap them more tightly to his pedals. She sewed padding into his cycling shorts.

In the spring of 1976, Greg won several more races on the intermediate circuit. He won so easily now that victory itself began to feel hollow.

LeMond in 1976, in a familiar pose.

Though he was fourteen, Greg petitioned racing officials to allow him to ride with the juniors, boys of sixteen through eighteen. Such permission was rarely granted; among teens, even a single year of maturity could confer an overwhelming advantage in size and strength. Yet the officials approved, bowing to Greg’s undeniable results. Now, he would face a much larger field of bigger, stronger boys, many of whom had been winning races for years.

A week before his fifteenth birthday, Greg entered the Nevada City Father’s Day Classic as a junior. This was one of the largest and oldest cycling events in the nation, drawing ten thousand spectators. Greg’s prior races had played out before thin crowds of parents and siblings.

Now, as he glimpsed the vast throng in Nevada City, Greg imagined what it must be like to race in Europe.

The Nevada City course was a one-mile loop that featured a short but steep ascent, a good setting for Greg to exploit his talents for aggressive climbing and swift recovery. But Greg was still an intermediate, and the rules confined him to relatively small gears compared to those of the older juniors, a measure meant to protect young legs from injury.

Out on the course, the gear restriction hindered Greg’s speed on the descents—he could not turn his pedals fast enough to keep up. Still, at the end of the race, Greg stood in second place. “It was then,” he recalled, “that I realized I could compete with some of the best American riders.”

The Sierra Nevada Sportswriter and Broadcaster Association named Greg athlete of the month. An interviewer asked him to quantify his ambitions.

“I’d like to turn professional and try to win the Tour de France, [and] the world professional championship,” Greg replied. “That’s the hardest kind of racing. I would like to win the Olympic gold medal in road racing—really, any medal.”

They were bold words. No American had taken any sort of medal in an Olympic cycling event since 1912. No American had ever won the men’s world-championship road race. No American had even entered the Tour de France.

That summer in Nevada, Greg happened upon Noël Dejonckheere, a native of cycling-mad Belgium, who was touring the United States and entering races. Noël was riding behind a pace car, his speed approaching forty miles per hour, when “this little kid” suddenly appeared alongside him. Noël invited Greg to join him on training rides. “He dropped me very easily,” Noël recalled, invoking cycling parlance for the act of riding away from one’s competitor. When Noël returned home, he told his family he might have met the next Eddy Merckx. Merckx was the world’s greatest male cyclist.

That fall, Greg enrolled at Wooster High School in central Reno. His arrival occasioned a reunion with Frank Kratzer, an old friend who had spent the prior two years at a different middle school. Once the pleasantries were past, Greg told Frank, “You’ve got to get a bike.” Frank traded his skateboard to a classmate for a bicycle. He presented it to Greg, who cried, “Let’s ride to my house!” Frank gamely joined him for the ninety-minute ride.

“Halfway there,” he recalled, “I was just dying.”

Gradually, Frank became Greg’s primary training partner, a role he played in a sort of tag team with Greg’s father. Greg became the mentor, Frank the student. Greg enlisted Frank in an ambitious weekly regimen inspired by his father’s exuberant work ethic, by his own burning ambition, and by the counsel of Noël Dejonckheere, who was now writing regularly from Belgium with advice.

Noël told Greg that races in Europe were twice the length of the thirty- and forty-mile contests staged for junior cyclists in the United States. He urged Greg to enter the longer races held for American seniors, and to ride hundreds of miles a week on his own, if he wished to become a professional one day.

Now Greg and Frank trained as hard as anyone in the Nevada-California racing circuit. Their week began on Tuesday with a ride of twenty to thirty-five miles, punctuated with a series of sprints. Wednesdays brought a longer ride, of fifty or sixty miles. Thursdays brought “intervals,” a punishing exercise in which Greg and Frank attacked a climb at top speed in a painfully large gear, pushing each boy’s heart rate to the peak for thirty or sixty seconds at a time. The boys would unwind on Fridays with a lighter ride of twenty miles. Saturdays and Sundays were for racing.

Greg and Frank spent idle hours in Greg’s room, listening to records and fantasizing about becoming rock stars. Greg “always had the best stereo,” Frank recalled, just as he had the best fishing pole and the best bicycle. His room was a Sharper Image catalog come to life.

The 1977 racing season dawned with Greg as the unrivaled star of the Reno Wheelmen. Greg strutted around the campus of Wooster High School asking befuddled classmates to place bets on his future prospects.

“I’m gonna win the Tour, and I’ll bet you a hundred bucks,” he would say. No one would take the bet; perhaps they weren’t quite sure which “Tour” he meant.

Now Roland Della Santa stepped forward to take an active role in Greg’s career. He took over sponsorship of the Reno Wheelmen, printing up Della Santa jerseys and building custom Della Santa bicycles for Greg and his team. Roland’s invisible partner in this arrangement was Greg’s father, who, unlike Roland, had the money to sponsor a bicycle team.

“I controlled the equipment, and Bob controlled the cash,” Roland explained. The team’s annual budget for its star rider came to $5,000.

That spring, at the Santa Clara Criterium, Greg humiliated a reigning junior national cycling champion by “lapping” him, riding so far ahead of the field that he circled the course and caught him from behind. In months to come, Greg would lap the nation’s top cyclists two or three times in a single race. The ease of his victories spawned an absurd rumor, fed in equal parts by television’s Six Million Dollar Man and by an old scar on the back of a calf, that Greg’s leg muscles had been transplanted from a kangaroo.

Racing officials now gave fifteen-year-old Greg permission to ride among seniors, the adults of bicycle racing. His first chance to challenge the cycling elite came in the three-day Tour of Fresno, a stage race modeled on the multiday races of Europe. This was a top-drawer contest, and it attracted members of the powerful Exxon cycling team. Their leader was John Howard, dean of American cyclists, four-time national champion and three-time Olympian.

In two days of intense racing, Howard and his Exxon team rode Greg to a stalemate. The contest came down to a final, ten-mile time trial, each cyclist riding alone against the clock. Now Howard was isolated from his team. In the first part of the course, riders rode into a headwind, and Greg amassed a ten-second advantage over Howard. Then the course turned, and the riders picked up a tailwind. That was disastrous for Greg. He still rode with smaller, age-restricted gears, and now he could no longer pedal fast enough to match Howard’s pace. The older rider pulled back the lost time and seized victory by a margin of six seconds.

Knowledgeable observers instantly recognized that the Reno teenager would have beaten the four-time American champion had he only pedaled a comparable bicycle. The LeMond legend was born.

With fame came nicknames: the Carson City Comet; the Reno Rocket; LeMonster. To Greg, nothing now seemed beyond reach.

Tuesday, May 15, 2018:

Interview with Dan de Visé

Author Dan de Visé will visit the U.S. Bicycling Hall of Fame on July 7 for a reading and signing of his new book, THE COMEBACK: Greg LeMond, the True King of American Cycling, and a Legendary Tour de France.

De Visé grew up in Chicago. He alternated going with his father, Pierre, to watch the Chicago Cubs play in nearby Wrigley Field, and watching track races on the Ed Rudolph Velodrome in suburban Northbrook.

After college at Wesleyan and Northwestern universities, de Visé served as a staff writer for newspapers including the Washington Post and Miami Herald and authored the acclaimed ANDY AND DON: The Making of a Friendship and a Classic American TV Show, about Andy Griffith and Don Knotts.

USBHOF Board Member Peter Joffre Nye interviewed de Visé about his new book.

Q: What inspired you to write THE COMEBACK, which you call “a great forgotten story”?

A: My agent, Deborah Grosvenor, really hammered in my head the need for a story about main characters living roller coaster ups and downs, forcing them overcome many obstacles. I was rummaging through my brain while walking through my neighborhood in suburban Maryland outside Washington, D.C., and I thought of all the things that Greg LeMond did.

Talk about ups and downs and overcoming obstacles! Greg came out of nowhere in cycling. He went to Europe and beat the best Europeans at their own game. Then after his first Tour de France victory in 1986 he went into decline. I knew there had been conflict and sharp words between him and Lance Armstrong. I presented a proposal about Greg’s career to my agent and she thought he had a great story.

Q: Besides enduring with ups and downs, LeMond had to overcome several serious betrayals.

A: Greg was betrayed by his team leader Bernard Hinault. Hinault had won the 1985 Tour with Greg’s help and promised to help Greg win it in 1986, only to ride against Greg in an attempt to win for himself. I have a whole chapter on that, “The Betrayal.”

Three years later, Greg was riding for the Belgian team ADR-Agrigel and had not been paid for months when he rode his greatest Tour in 1989, his second Tour victory.

Q: You depict a poignant scene in Paris on the afternoon in July 1989. Greg had won the Tour and his ecstatic teammates took him away to celebrate. His wife, Kathy, was left behind near the finish line. She’s penniless because the team hasn’t paid him.

A: She didn’t have cab fare to for a ride back to their hotel.

Q: Then there was more betrayal after Lance Armstrong and the war of words between him and Greg.

A: Lance and Greg were the two people who accomplished the most in modern cycling. It’s surprising to me that so few people know about Greg. Now since Lance’s fall from grace Greg is the most decorated U.S. rider. I wish there were 10 books on Greg. Perhaps there will be one day.

Q: While The Comeback is framed around the epic time trial on the final day of the 1989 Tour de France, burning up the road faster than leader Laurent Fignon to score an upset victory, you continued with Greg’s personal story—his career, his personal life, through 2017.

A: The ADR team Greg rode for when he won the 1989 Tour is probably one of the worst in Tour history that produced a winner. His Belgian teammate Johann Lammerts defends the team, saying they were good riders. They were good for crits. One rider was a decent sprinter. But Greg was completely on his own in the Alps and the Pyrenees.

The 1990 new French team Greg joined helped him win his third Tour.

Q: How would you rate LeMond’s feat winning the 1989 Tour by clinching the time trial compared with landmark moments among other sports—like Babe Ruth’s famed “called shot” home run for the Yankees at Wrigley Field in the 1932 World Series?

A: Objectively, Greg’s victory in that Tour was a big enough deal that Sports Illustrated picked him, then a not-very-well known athlete in America, competing in an obscure sport, as Sportsman of the Year. The magazine’s writers picked him rather than a baseball player or football player.

Over the years, the massiveness of Greg’s career has been diminished by the comeback of Lance Armstrong. It’s weird, like if Babe Ruth hit 60 home runs and another player hit 65 home runs.

The thing about Greg is that the first year he competed in the Tour, he finished third. The second Tour, he finished second. The third time, Greg won. He was always consistent.

I intended this to be a celebratory book about Greg, but toward the end it gets dark.

Q: Often when writers work on biographies, they can grow disillusioned with the person or worse. What kept you going?

A: The more I learned about Greg and Kathy LeMond, the more I admired them. I think that one reason more hasn’t been written about is that he’s elusive. Greg and Kathy are so busy. I flew to Minneapolis and met with Kathy one day and Greg met with me the next day. They are wonderful people. I wouldn’t write a book about someone I didn’t admire. Neither one of them is perfect. Greg can be forgetful.

I spent a lot of time thinking about Lance as a person. I was a big Lance fan when he was winning Le Tour and I bought his book for my dad. My father died before the undoing of Lance’s legacy.

What a blessing it is for a writer like me to have a subject like Greg to overcome his battle of words with Lance. It turned out that Lance fell into disgrace as Greg’s star rose. Greg remains the only U.S. cyclist ever to win the Tour de France, and he won it three times.

Q: How long did it take you from an idea you had formed while walking around your neighborhood to copies that will be available in the Hall of Fame in July?

A: I had the idea in summer 2015. I finished a proposal in fall of that year. I wrote the book mostly in 2016 and handed it in around spring of 2017. So, roughly a two-year process, but then there’s been another year of editing, fact-checking, photo-gathering and such. I last met with Greg in October 2017.

Q: You inform readers on this side of the Atlantic about the late Laurent Fignon. He sounds like a really noble character.

A: I interviewed his widow, his ex-wife, his soigneur and several of his old friends. I thought Laurent was sweet-natured. And he was very candid. Also very shy. He didn’t know what to do with the crowds that he drew, so he would push his way through the throngs that followed him.

Q: Who were some of your influences as a writer?

A: In my wildest dreams I think of this book in the tradition of Laura Hillenbrand’s Seabiscuit and Daniel James Brown’s Boys in the Boat. I was inspired by Richard Moore’s Slaying the Badger: LeMond, Hinault, and the Greatest Ever Tour de France.

I’m transfixed by really good narrative nonfiction. I like the work of Mark Bowdon, author of Black Hawk Down, and Jon Krakauer’s Into Thin Air.

Q: With all of the obstacles Greg LeMond put up with during his cycling career and afterward with his battles against Lance, the way you write of these developments come across as a ten-part mini-series waiting to go into production.

A: Yeah, that would be great!