Cycling’s Twenty-One Greatest Climbers

BikeRaceInfo's Best Climbers: Riders 5 -1

Les Woodland's book Cycling 50 Craziest Stories is available as an audiobook here. For the print and Kindle eBook versions of the book, just click on the Amazon link on the right.

Riders are listed in reverse order. Rider number one will be the rider in our judgement to be cycling's greatest ever climber.

Cycling's Greatest Climbers intro | Climbers 17–21 | Climbers 16–11 | Climbers 10–6

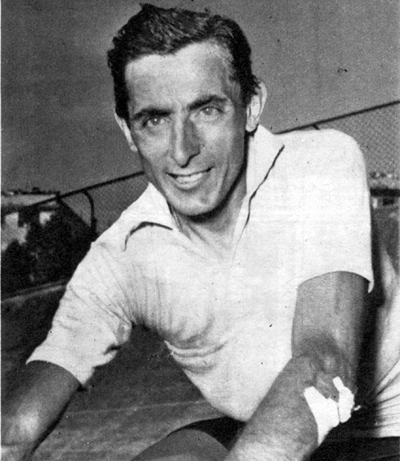

5. Gino Bartali (1914–2000)

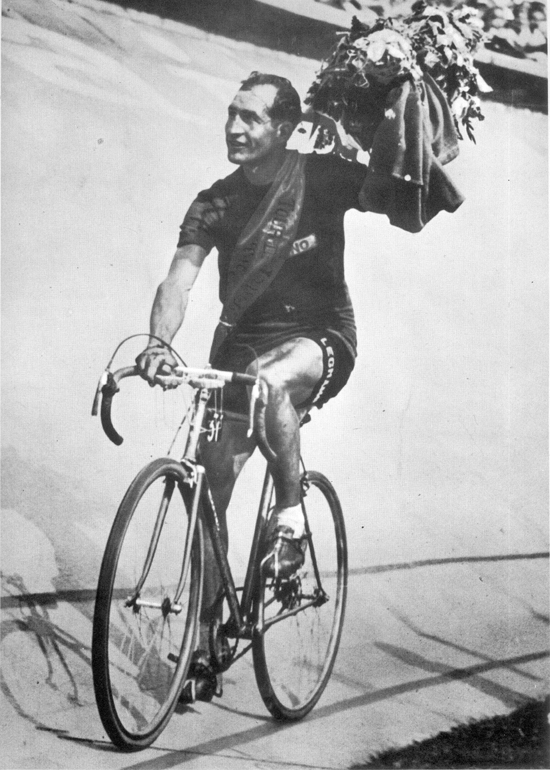

Gino Bartali has just won the 1948 Tour de France.

Gino Bartali won the big ones: Tour de France twice, Giro d’Italia three times (with seven King of the Mountains titles), Milano–San Remo four times and the Giro di Lombardia three times. And that’s just the really big stuff. Bartali is particularly well-known for holding the record for the longest time between Tour de France wins, ten years.More importantly, during World War Two, Gino Bartali worked to save Jews in German-occupied Italy. He smuggled documents and provided a Jewish family with an apartment he owned. That brave work dwarfs his racing accomplishments.

Bartali possessed an astonishing talent. At age twenty (1935), he was already a Giro d’Italia King of the Mountains, Italian Road Champion and had won the prestigious Coppa Bernocchi and Tour of the Basque Country.

Through the pre-war years the incredibly talented Bartali assembled an astonishing list of wins, though most were secured in his home country. After winning the 1936 and 1937 Giro d’Italia and crashing out of the 1938 Tour de France, the Mussolini government asked him to forego an attempt on the Giro and concentrate on trying to win the Tour de France; at that time the Tour used national teams rather than trade teams.

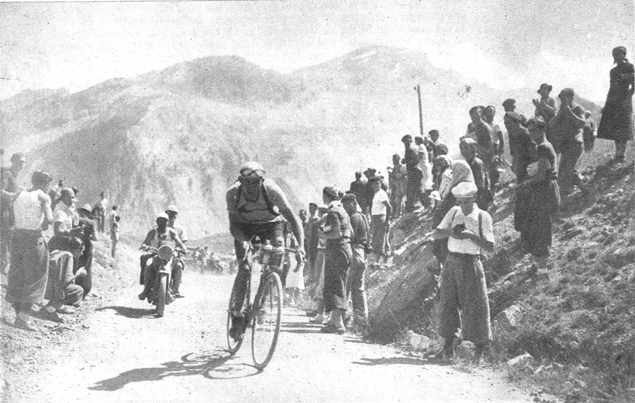

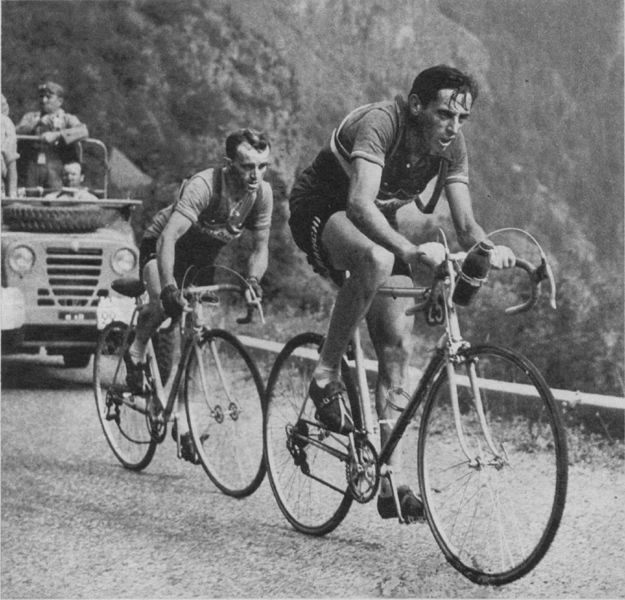

Bartali races up the Col de Vars in the 1938 Tour de France.

Bartali was successful, winning the 1938 Tour by more than eighteen minutes.

In the 1939 Giro, Bartali battled with a (now) poorly-known but titanically talented rider named Giovanni Valetti, who beat Bartali by nearly three minutes. More importantly, on June 4, a couple of weeks after the Giro concluded, 20-year-old Fausto Coppi, in the words of Philippe Brunel, “arrived on the scene and scrambled Bartali’s orderly life” by breaking away from the pack in the Tour of Piedmont. He was caught after his chain began slipping and finished third behind the day’s winner, Bartali. Coppi’s masseur, Giovanni Cavanna, told Eberardo Pavesi about his young athlete’s extraordinary ability. That evening Legnano team boss Pavesi signed Coppi to be a gregario for Bartali.

It all came to play in the 1940 Giro d’Italia. Gino Bartali was the leader of the Legnano team at the race's start, but he crashed and lost time in the second stage. The new gregario hired to help Bartali, Fausto Coppi, became the team leader. In stage eleven, Coppi attacked on the Abetone pass and at the end of the stage became the maglia rosa. Despite some trouble in the high mountains, Coppi went on to win the first of his five Giri and became the youngest ever Giro winner. The competition between Bartali and Coppi consumed Italy and didn’t really relent until the 1949 Tour de France, where Bartali worked for Coppi.

Bartali never again won a Grand Tour, though he had many more prestigious race wins left in him before retiring in 1953.

Gino Bartali raced professionally from 1935 to 1953.

Bartali’s Major Accomplishments:

- 1935: Giro d’Italia Mountains Classification; Italian Road Championships; Coppa Bernocchi; Tour of the Basque Country

- 1936: Giro d’Italia General and Mountains Classifications, winning three stages; Giro di Lombardia

- 1937: Giro d’Italia General and Mountains Classifications, winning four stages; Giro del Lazio; Giro del Piemonte

- 1938: Tour de France General and Mountains Classifications, winning two stages; Tre Valli Varesine

After the 1938 Tour’s thirteenth stage on Thursday, Bartali was in second place, 1 minute 35 seconds behind Félicien Vervaecke. Bartali’s fourteenth stage of the 1938 Tour de France is the stuff of legends. Riding first over the Allos, Vars and Izoard, Bartali accrued 5 minutes 43 seconds in time bonuses before rolling into Briançon 5 minutes 18 seconds ahead of Mario Vicini. The result: Bartali now led the Tour, more than seventeen minutes ahead of second-place Mathias Clemens. By the end of the 1938 Tour de France Bartali has built an eighteen-minute lead over second-place Félicen Vervaecke.

- 1939: Milano–San Remo; Giro di Lombardia; Giro del Piemonte; Giro della Toscana; Giro d’Italia Mountains Classification, winning four stages

- 1940: Italian Road Championships; Giro d’Italia Mountains classification; Milano–San Remo; Giro di Lombardia; Giro della Toscana

- 1945: Giro di Campania

- 1946: Giro d’Italia General and Mountains Classifications; Tour of Switzerland; Trofeo Matteotti; Zürich–Metzgete

- 1947: Giro d’Italia Mountains Classification, winning two stages; Milano–San Remo; Tour of Switzerland; Giro della Toscana

- 1948: Tour de France General and Mountains Classifications, winning six stages; Zürich–Metzgete

It is for the 1948 Tour de France that Gino Bartali should be particularly remembered. Going into the twelfth stage, ten years after he had won his first Tour and now in seventh place, more than 21 minutes behind leader Louison Bobet, Bartali proceeded to perform the unbelievable. By the end of the 1948 Tour de France he had won the Overall General Classification, King of the Mountains and seven stages. Second place Briek Schotte was more than 26 minutes behind. It was an incredible performance.

- 1949: Tour de Romandie

- 1950: Milano–San Remo, Giro della Toscana

- 1951: Giro del Piemonte

- 1952: Italian Road Championships, Giro dell’Emilia

- 1953: Giro della Toscana; Giro dell’Emilia

Gino Bartali with Greg LeMond in the 1993 Giro d'Italia.

4. Federico Bahamontes (1928– )

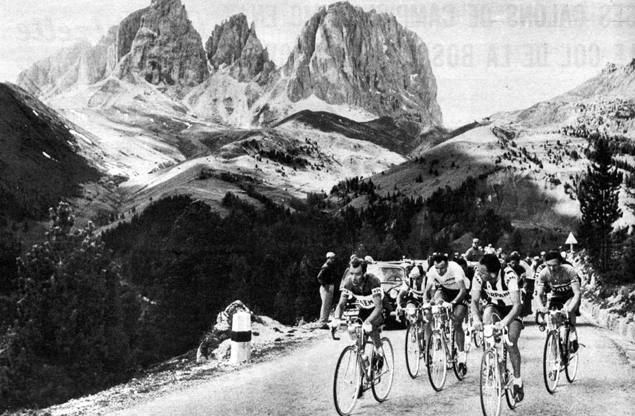

Bahamontes races in the 1956 Giro d'Italia.

Weird, wonderful, talented Federico Bahamontes (born Alejandro Martin Bahamontes) was surely the 1950s' greatest specialist climber. He has only one Grand Tour victory (1959 Tour de France), but won nine Grand Tour Mountains Classifications and eleven Grand Tour stages. He deserved his nickname “The Eagle of Toledo”.

His first Grand Tour was the 1954 Tour de France, where he won the Mountains Classification, though he was rather unrealistically told to also go for the overall victory (he came in 25th).

Bahamontes did win a Grand Tour, the 1959 Tour de France, amid confused French team politics. In those days teams were aligned according to national and regional lines, for example France, Belgium, Spain and Centre-Midi. Bahamontes rode for Spain, managed by Fausto Coppi, who convinced the Spaniard to win the Tour de France rather than be content with the Mountains Classification.

Complicating the 1959 Tour de France, there was a network of shared agents, and each rider wanted his agent to represent the most successful riders, therefore giving him more power. Jacques Anquetil, Federico Bahamontes and Roger Rivière were represented by this most powerful agent, Daniel Dousset. This made a secret team working to make Dousset’s riders prevail.

Bahamontes races the 15th stage of the 1959 Tour de France.

The most talented man riding who was not represented by the most powerful agent of this network was Henri Anglade. This strange situation came to a head during the closing moments of the eighteenth stage. Anglade took off and Yellow Jersey Federico Bahamontes could not follow him. French riders Jacques Anquetil and Roger Rivière pulled him up to Anglade. That ended any real peril to Bahamontes' final victory; the Spaniard beat second-place Henry Anglade by more than four minutes. It was a sordid episode that reflected poorly on Anquetil and Rivière.

Bahamontes was famous for his superb climbing and poor descending, usually refusing to descend alone after landing in a cactus while racing as an amateur.

Bahamontes rode professionally from 1953 to 1965.

Bahamontes Major Accomplishments:

- 1954: Tour de France Mountains Classification

Bahamontes finished the 1954 Tour with a large winning margin in the Mountains Classification. Bahamontes 95 points, Louison Bobet 53 and Richard van Genechten 45.

- 1955: Vuelta a Asturias

- 1956: Fourth General Classification, Second Mountains Classification Tour de France; Fourth General Classification, Second Mountains Classification Vuelta a España

- 1957: Second Place General Classification, Winner Mountains Classification Vuelta a España; Tour of Asturia

- 1958: Champion of Spain; Best Climber, eighth place, Tour de France; Best Climber, sixth place Vuelta a España

Bahamontes won a commanding victory in the 1958 Tour’s fourteenth stage. He was first over the Aspin and Peyresourde and rolled into Luchon alone, about two minutes ahead of the chasing field. He did it again in stage twenty where he crested the Izoard first, before rolling into Briançon alone. Bahamontes finished the 1958 Tour eighth, 40 minutes 44 seconds behind winner Charly Gaul. In the 1958 Tour the climbs were broken down to four categories, the harder ones giving the climb winners more points. There was no climber’s jersey in 1958, but Bahamontes won the classification in commanding fashion, 137 points to second place’s Imerio Massignan who earned 77.

- 1959: General Classification and Mountains Classifications Tour de France; Mountain Classification and Third-Place GC Tour of Switzerland; Second place Spanish Road Championships

- 1962: Mountains Classification Tour de France; Fourth place Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré

Bahamontes came to the 1962 Tour de France in superb form, winning the stage thirteen uphill time trial. Eventual winner Jacques Anquetil feared Bahamontes' excellent condition and somehow inveigled the Spaniard to waste lots of energy and lose huge amounts of time in the fourteenth stage.

- 1963: Mountains Classification, Second Place Overall, Third Place Points Tour de France; Second Place Tour de Romandie; Mountains Classification Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré

Bahamontes escaped in the first stage of the 1963 Tour de France setting himself to be well-positioned when the mountains arrived. At the start of stage nine, before the climbing, eventual winner Jacques Anquetil was eighth, at 6 minutes 14 seconds, and Bahamontes was twelfth, down 7 minutes 33 seconds. At the end of nine straight stages of climbing, Anquetil surprised all with his depth by being in the lead, stalked by Bahamontes at 28 seconds. Except for Anquetil extending his lead to 3 minutes 35 seconds, that is how the 1963 Tour de France ended, an Anquetil/Bahamontes one-two.

- 1964: Mountains Classification, Third place GC, winning two stages, Tour de France

Bahamontes congratulates Pierre Rolland in the 2013 Tour de France. Photo © Sirotti

3. Marco Pantani (1970–2004)

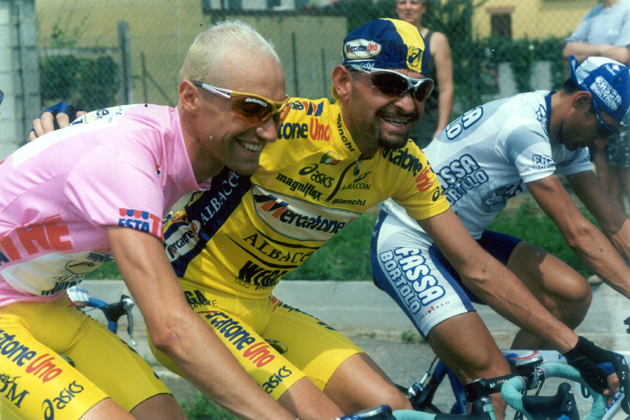

Marco Pantani at his peak. Felice Gimondi lifts his arm in congratulations after Pantani has won both the 1998 Giro d'Italia and Tour de France. Bobby Julich is in the lower right corner.

Without a doubt, Marco Pantani was the most extraordinary climber of his era and one of the greatest ascenders ever. His climbing ability allowed him to do what few racers could ever accomplish, win the Giro d’Italia and the Tour de France in the same year; in Pantani’s case, 1998.

After winning the 1992 amateur Giro d’Italia, Pantani turned pro, racing for Davide Boifava and his Carrera Jeans-sponsored team. Pantani’s outstanding climbing skills made it obvious he was going to be a success.

In 1994 he hit his stride, coming in second in the Giro d’Italia and third in the Tour de France, winning the French race’s young rider classification. This was racing at the highest level.

Pantani triumphs in the 1995 Tour de France. Photo ©Sirotti

In 1995, he was hit by a car, preventing his racing the Giro d’Italia, but he did ride the Tour, winning two stages and again, the best young rider classification. After taking third in the 1995 World Championships in Colombia, Pantani was again hit by a car. This time the accident looked career-ending. It wasn’t, but Pantani had to miss most of the 1996 season.

In 1997 a new team sponsored by Italian retailer Mercatone Uno was formed around Pantani, using, among others, ten riders from the now-defunct Carrera squad to ride as Pantani’s supporters. Pantani crashed out of the Giro d’Italia but did finish the 1997 Tour de France third to Jan Ullrich and Richard Virenque, winning two stages.

In 1998, Pantani hit the sweet spot. He won the Giro d’Italia, taking the Mountains Classification and winning two stages. His first 1998 Giro stage win was the fourteenth leg, finishing at the Piancavallo ski resort, which moved Pantani to second place, 22 seconds behind leader Alex Zülle. Pantani lost almost four minutes in the next stage’s 40-kilometer individual time trial. It didn’t matter, Pantani was on fire. He took the lead for good after finishing second to Giuseppe Guerini in the massive seventeenth stage.

Pantani won the Giro’s nineteenth stage at the top of Pian di Monte Campione, creating a lead large enough to withstand a final individual time trial challenge.

Complaining that he was tired, Pantani nevertheless entered the 1998 Tour de France. Unsurprisingly, he lost gobs of time (4 minutes 21 seconds) to Jan Ullrich in the stage seven individual time trial. When the Tour its the first Pyrenean stage, Pantani made it clear he was going to be able handle himself, finishing seconds, 36 seconds behind stage winner Rodolfo Massi. Then the next day Pantani won the massive eleventh stage with five massive climbs. Ullrich still led, but one could see the German’s time in Yellow was limited.

Pantani wins 1998 Tour de France stage 15. Photo ©Sirotti

It was in the fifteenth stage that Ullrich’s lack of deep conditioning and Pantani’s sparkling form both showed. Pantani won the stage alone at Les Deux Alpes, almost nine minutes ahead of Jan Ullrich. Pantani was in Yellow and Ullrich’s chances for winning the 1998 Tour de France were finished.

Pantani won the 1998 Tour de France, finishing 3 minutes 21 seconds ahead of Jan Ullrich, being the first rider to accomplish the Giro-Tour double since Miguel Indurain in 1992 and 1993.

Pantani started 1999 as the heavy favorite, and after winning stage twenty atop Madonna di Campiglio, led general classification second-place Paolo Savoldelli by 5 minutes 38 seconds. Before riding stage twenty-one Pantani was subjected to a hematocrit test, which he failed. Pantani was ejected from the 1999 Giro, which was eventually won by Ivan Gotti. Pantani rode no more races in 1999.

Pantani was never the same rider after his 1999 Giro expulsion. He rode the 2000 Giro d’Italia in support of teammate and eventual winner Stefano Garzelli and then went on to ride the Tour de France. He started off-form, but by stage twelve he was able to match Lance Armstrong up Mont Ventoux. The two were soon feuding. Pantani won stage fifteen with its Courcheval finish, his last professional victory. The next stage, Pantani mounted a long-range break, but failed to finish the stage.

Pantani was the subject of several doping investigations, but it all came to an end on February 14, 2004. Pantani died from acute cocaine poisoning alone, in a hotel room in Rimini, Italy. It turns out that after being tossed from 1999 Giro Pantani had taken up the dangerous drug.

Pink-jerseyed Stefano Garzelli rides with Marco Pantani in 2000. Photo ©Sirotti

Marco Pantani raced professionally from 1992 to 2003.

Marco Pantani’s Major Professional Accomplishments:

- 1992: 3rd place Memorial Nencini

- 1993: 5th place Giro del Trentino

- 1994: Giro d’Italia second place General Classification, third place Mountains Classification, winning 2 stages; Tour de France third place General Classification, second place Mountains Classification, first place Young Rider; fourth place Giro del Trentino

- 1995: third place World Road Championships, Tour de France Young Rider Classification, winning two stages

- 1997: third place Tour de France, winning two stages; third place Vuelta al Pais Vasco; fourth place Critérium International

- 1998: Tour de France General and Mountains Classifications, winning two stages; Giro d’Italia General and Mountains Classifications, winning two stages; third place Tour of Murcia; fourth place Giro del Trentino

- 1999: Vuelta a Murcia General and Mountains Classifications, third place Giro del Trentino; Giro d’Italia four stage wins before expulsion

- 2000: Tour de France two stage wins before abandoning

2. Fausto Coppi (1919–1960)

Stories about Coppi on our site:

Coppi and Bartali

Mahé, Coppi and Paris–Roubaix

Fausto Coppi after winning the 1952 Giro d'Italia.

I believe Angelo Fausto Coppi to be cycling's finest all-around rider ever. Not the greatest: that category I reserve for Eddy Merckx. Coppi was surely the finest, most elegant cyclist in the history of the sport. He won nearly everything, single-day races, stage races, grand tours, time trials, track races, even the World Hour Record.

The Italians nicknamed him Il Campionissimo, or Champion of Champions.

A quick look at his war-interrupted record of Grand Tour wins shows what an extraordinary rider he was:

Tour de France: 1949 & 1952 General and Mountain Classifications

Giro d’Italia: 1940, 1947, 1949, 1952, 1953 General Classification, winning the Mountains Classification in 1948, 1949 and 1954, taking twenty-two stage wins along the way.

His family knew the boy had a passion for cycling and an uncle paid to have a racing bike custom-built for the 15-year-old boy. But after coming to the custom cycle shop for weeks and finding no made to measure bike as had been agreed upon, the shop owner relented, cheating the lad by giving him a stock bike. Coppi entered his first race at the age of 15, and won it, alone.

By 1939 Coppi was entering and winning races riding as an independent, a class of riders who could compete in both amateur and professional races. He had also begun working with Biagio Cavanna, a blind former boxer who worked as Coppi’s masseur and trainer.

Coppi was hired to ride as a gregario for Legnano team leader Gino Bartali in the 1940 Giro d’Italia. Bartali crashed and lost an unrecoverable amount of time in the second stage, while Coppi had finished second that day. Coppi found fame in stage eleven when he soared over the Abetone Pass and finished in Modena alone, more than a minute ahead of his nearest chaser and more than ten minutes in front of most of the field. He had taken the Giro’s lead and kept it to the finish in Milano.

Gino Bartali leads Coppi in the 1940 Giro d'Italia.

About Coppi, I wrote this in The Story of The Tour de France:

“Comparing riders from different eras is a risky business subject to the prejudices of the judge. But if Coppi isn't the greatest rider of all time, then he is second only to Eddy Merckx. One can't judge his accomplishments by his list of wins because World War II interrupted his career just as World War I interrupted that of Philippe Thys. Coppi won it all: the world hour record, the world championships, the grands tours, classics as well as time trials. The great French cycling journalist, Pierre Chany says that between 1946 and 1954, once Coppi had broken away from the peloton, the peloton never saw him again. Can this be said of any other racer? Informed observers who saw both ride agree that Coppi was the more elegant rider who won by dint of his physical gifts as opposed to Merckx who drove himself and hammered his competition relentlessly by being the very embodiment of pure will.”

Coppi’s intense rivalry with Gino Bartali in many ways summed up Italy. Bartali was revered by the agrarian south and Coppi was worshiped in the industrial north. The rivalry between the two hit nadir in the 1948 World Road Championships held in Valkenburg, Netherlands. The pair so intensely marked each other, ignoring the rest of the competitors and their job to see that Italy did well, they finally just stopped and climbed off their bikes.

It was on the Col d’Izoard in the 1952 Tour de France that the first signs of a thaw between Coppi and Bartali began to show. The pair shared a bottle, but then argued over who had offered it. Still, Bartali was aging and knew it. The pair reconciled and became good friends.

Coppi leads Jean Robic in the 1952 Tour de France.

Coppi’s last great year was 1953, when he won the Giro (taking four stages) and the World Road Championships. He had big race wins left in him, but from then on the magic seemed to be gone.

Late in 1959 Coppi, along with Jacques Anquetil, Louison Bobet, Roger Hassenforder, Henry Anglade and Raphaël Géminiani traveled to Burkina Faso to hunt and race. The hotel was infested with mosquitos. Both Coppi and his roommate Géminiani caught a dangerous strain of malaria. Géminiani was correctly diagnosed and recovered, but Coppi was not treated for malaria, but instead for several other bronchial infections. Coppi died from the malaria infection, January 2, 1960.

Fausto Coppi rode as an independent in 1939 and professionally from 1940 to 1959.

Coppi’s major cycling accomplishments:

- 1939: second Place Coppa Bernocchi

- 1940: General Classification, second place Mountains Classification Giro d’Italia; Italian Pursuit Championships

- 1941: Giro dell’Emilia; Giro di Toscana; Giro del Veneto, Tre Valli Varesine; Italian Pursuit Championships

- 1942: Italian Road Championships; Italian Pursuit Championships; World Hour Record (45.871 km/hr)

- 1946: Milano–San Remo; Giro di Lombardia; GP des Nations; Giro di Romagna; second place Giro d’Italia, winning three stages

Fausto Coppi’s 1946 Milano–San Remo is the stuff of legends. He broke away with nine other riders when the race was just five kilometers old. He left the others behind on the Turchino climb to solo in to San Remo after eight hours of racing, fourteen minutes ahead of second-place Lucien Teisseire. The next group, containing Gino Bartali, Vito Ortelli and Adolfo Leoni, finished more than eighteen minutes behind Coppi.

- 1947: Giro d’Italia, winning three stages; Giro di Lombardia; GP des Nations; Giro dell’Emilia; Giro di Romagna; Giro del Veneto; Italian and World Pursuit Championships

- 1948: Milano–San Remo; Giro di Lombardia; Giro dell’Emilia; Tre Valli Varesine;second Het Volk; first-place Italian and second-place World Pursuit Championships

- 1949: Tour de France General and Mountains Classifications, winning three stages; Giro d’Italia General and Mountains Classifications, winning three stages; Milano–San Remo, Giro di Lombardia; Giro di Romagna; Giro del Veneto; Italian Road Championships; World Pursuit Championships

Fausto Coppi’s 1949 season was extraordinary. He became the first man to win the Giro d’Italia and the Tour de France in the same season. He not only won the two big Grand Tours, his Classics season was sparkling with victories in Milano–San Remo and the Giro di Lombardia.

- 1950: Paris–Roubaix; La Flèche Wallonne; Giro della Provincia di Reggio Calabria

Coppi broke his pelvis in the 1950 Giro d’Italia, one of many serious breaks the racer endured during his professional career. It has been speculated that malnutrition caused by childhood poverty left him with fragile bones. It has been further speculated that the almost annual bone fractures Coppi suffered broke up his racing seasons and allowed him to recover and race the competitions he did enter with greater vigor and strength.

- 1951: GP di Lugano; fourth place Giro d’Italia, winning two stages

1951 was a difficult year for Fausto Coppi. His beloved brother Serse died five days before the Tour de France’s start, leaving Fausto an emotional wreck and unable to win an important race that year.

- 1952: Tour de France, winning five stages; Giro d’Italia, winning three stages; GP Mediterraneo, winning two stages; second place Paris-Roubaix

Coppi’s 1952 Giro was extraordinary. He delivered a dominating ride that crushed one of the finest starting fields in Giro history. He left second-place Fiorenzo Magni more than nine minutes behind. By end of the eleventh stage of the Tour de France, Coppi’s lead was so large the organizers doubled the prize money for second place, hoping to enliven the race. For the second time, Coppi did what no other rider had ever been able to accomplish, win the Giro and the Tour the same year.

- 1953: Giro d’Italia, winning four stages; Trofeo Baracchi (with Riccardo Filippi); World Road Championships

- 1954: Giro di Lombardia; Coppa Bernocchi; Giro di Campania; Trofeo Baracchi (With Riccardo Filippi); fourth place Giro d’Italia

- 1955: Giro dell’Appennino; Giro di Campania; Tre Valli Varesine; Trofeo Baracchi (with Riccardo Filippi); second place Giro d’Italia; second place Paris–Roubaix; second place Giro di Romagna

- 1956: GP de Lugano; second place Giro di Lombardia; second place Coppa Bernocchi; second place Trofeo Bernocchi with Riccardo Filippi

- 1957: Trofeo Baracchi with Ercole Baldini

The great men of their era, from left: Fiorenzo Magni, Gino Bartali and Fausto Coppi.

1. Charly Gaul (1932–2005)

Charly Gaul (left) and Louison Bobet in the 1955 Tour de France.

From Volume 1 of The Story of the Giro d’Italia: “Charly Gaul was one of the most exciting, exasperating and enigmatic riders of the 1950s. He turned pro in 1953 at the age of 20. By 1955 the slight, fragile-looking Luxembourger had established himself as the sport’s finest climber. In the 1955 Tour he won two mountain stages, the mountains prize and third place in the Overall. He quickly developed the maddening style of inattentive and lazy racing during the flat stages where he would give up gobs of time, knowing that he could explode in the mountains and leave the others many minutes behind. Sometimes he would rip a race apart and sometimes, inexplicably, Gaul would just do nothing. Like most of the riders of the 1950s, Gaul used amphetamines. It has to be emphasized that there were no drug tests and the modern opprobrium regarding drug-taking was not then the norm.

“But Gaul admitted that he took drugs in larger amounts than the others and the results showed in his racing. The hyperthermia that amphetamine use can induce gave Gaul the ability to race in cold and wet conditions but caused him to suffer unbearably on hot days, sometimes even forcing him to jump into city fountains in the middle of a race. There are pictures of Gaul (and a lot of other riders of his era) glassy-eyed with flecks of dried foam around his lips, sad testimony that Gaul did what he believed he had to do in order to be who he had to be. I am sure a lot of his erratic behavior is explainable by his heavy drug use.

“An example of Gaul’s willingness to lose time: Going into the Giro d’Italia’s legendary stage twenty, Gaul was sixteen minutes behind race leader Pasquale Fornara. Yet, wearing a short-sleeve jersey, Gaul climbed Monte Bondone through snow and ice while more than 60 riders abandoned. He emerged at the top of the mountain the GC leader and went on to be the final victor of the 1956 Giro d’Italia.”

Charly Gaul's legendary ascent of Monte Bondone in the 1956 Giro d'Italia.

With rare exception, when Gaul wanted ride away from the field on a climb, he could just go and no one was able to match his uphill speed. Nicknamed "The Angel of the Mountains", Charly Gaul was extraordinary.

For such a fine climber, Gaul was a surprisingly fine time trialist, making him a potent stage racer (he won all the time trials in the 1958 Tour de France, even beating Jacques Anquetil). He was also an accomplished cyclo-cross racer.

Gaul raced professionally from 1953 to 1965.

After retiring he opened a bar, but closed it after a few months and went to live in the Ardennes Forest as a recluse. Only in the early 1980s did he come back out into the world, an old, bearded fat man who had lost most of his memory. Gaul died in 2005.

Charly Gaul on his way to winning the 1958 Tour de France

Charly Gaul’s major accomplishments:

Tour de France:

- 1958 General Classification

- 1955, 1956 Mountains Classification

- Ten stage wins

Giro d’Italia

- 1956, 1959 General Classification

- 1956, 1959 Mountains Classification

- Eleven stage wins

Six times Luxembourg National Road Champion

Charly Gaul (left, Faema jersey) leads the field in the 1958 Giro d'Italia.

Cycling's Greatest Climbers intro | Climbers 17–21 | Climbers 16–11 | Climbers 10–6