Wheel Building

Part 4: Making a Wheel Round,

The Holy Grail of Wheel Building

by John Neugent

Tech articles | Commentary articles | Wheel building part 3 | Wheel building part 5

John Neugent probably knows more about bicycle wheels than anyone else alive. Maybe more about bikes as well. He's spent his life in the bike business, at every level. He now owns Neugent Cycling, a firm devoted to delivering world-class equipment at the lowest possible price. If you are in the market for a set of wheels, please, check out John's site. He really knows his stuff. —Chairman Bill

John Neugent

Les Woodland's book The Olympics' 50 Craziest Stories: A Five Ring Circus is available as an audiobook here. For the print and Kindle eBook versions, just click on the Amazon link on the right.

John Neugent writes:

When I first started building wheels in the early '70s my main focus was keeping the wheel straight laterally. That’s not only what I noticed, but also was where the caliper brake pads engaged. If the wheel was out of true it rubbed the brake pads. Further, the radial run out, or roundness, was very difficult to see because there is a tire on the rim.

Back in the '70s wheels were generally overbuilt. Aerodynamics was never considered to be that important. People wore fuzzy wool instead of lycra. Most bikes had 36 spokes. Spokes dramatically increase drag by performing like little egg beaters churning up the air.

Aerodynamics was perceived as so unimportant that when Shimano tried to make a big splash in the late '70s by designing their whole line with improved aerodynamics, people thought it was a joke.

Mavic realized that by reducing spoke count much lower than the norm, they could decrease drag and weight, and they were the first introducing wheel systems so constructed. Instead of 32- and 36-spoke wheels they became 20- and 24-spoke wheels – sometimes even less.

With the introduction of lower spoke counts on wheels, build quality became important. With fewer spokes, spoke breakage and rim cracks became more common. High and equal tension became the mantra. I did some consulting work with Velomax (bought by Easton) who wanted to set up wheel building production using sound tone. He had already used tone to inspect built wheels, plucking the spokes like strings. He wanted to change his production method to use tone to also tension a wheel.

The thing I found a little odd was that his wheel builder (he had only one) would build without using any tone but when the wheels were inspected, they had good even tone. What was the factor that resulted in even tone?

It was actually quite simple and logical, it was radial run-out or roundness. Since the spokes radiate from the hub, the biggest factor in tension is going to be radial.

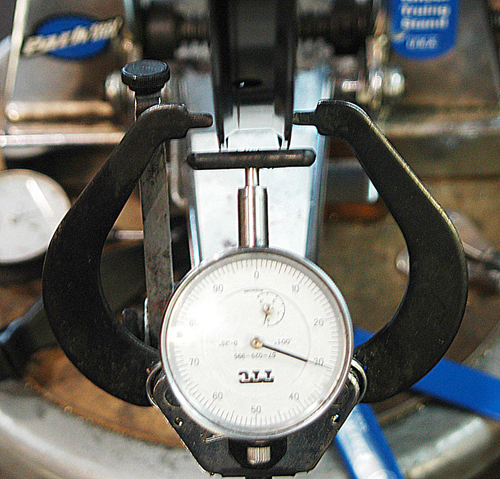

One of the very complicating factors in this is that almost no truing stands used dial indicators – which give you exact numbers and magnify movement making it easier to see and adjust. While lateral run-out is relatively easy to see without a dial indicator, radial run-out is not. The solution is to install dial indicators on the truing stands.

Wheel truing stand with dial indicator

I look at this two ways, the first being radial run-out is the Holy Grail, but also a radial reading dial indicator is its companion.

John Neugent was was one of the first to establish quality hand building in Taiwan around the turn of the century. He now owns Neugent Cycling, a firm devoted to delivering world-class equipment at the lowest possible price.

.