1998 Giro d'Italia

81st edition: May 17- June 7

Results, stages with running GC, map, photos and history

1997 Giro | 1999 Giro | Giro d'Italia Database | 1998 Giro Quick Facts | 1998 Giro d'Italia Final GC | Stage results with running GC | The Story of the 1998 Giro d'Italia

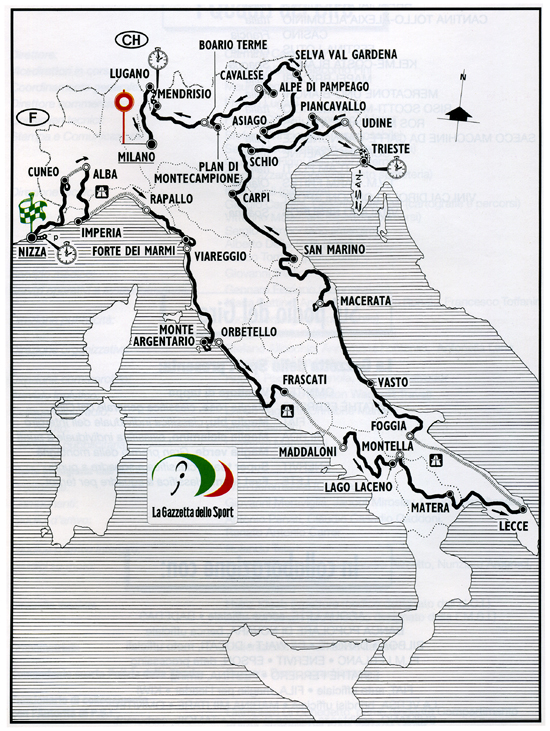

Map of the 1998 Giro d'Italia

Going into the 1998 Giro, two-time Vuelta winner Alex Zülle seemed to be the strongest rider.

In fact, Zülle was supreme for the first two weeks. When the race hit the Dolomites Marco Pantani applied unrelenting pressure. None could withstand his attacks and Zülle collapsed.

The bigger surprise was the final time trial, where 1996 Giro winner Pavel Tonkov should have had the advantage.

Pantani surprised everyone by coming in third and beating Tonkov by five seconds.

Pantani went on to win the Tour de France that summer, earning the rare Giro/Tour double.

David L. Stanley's book Melanoma: It Started with a Freckle is available as an audiobook read by the author.

1998 Giro d'Italia Complete Final General Classification:

Marco Pantani (Mercatone Uno) 98hr 48min 32sec

Marco Pantani (Mercatone Uno) 98hr 48min 32sec - Pavel Tonkov (Mapei) @ 1min 33sec

- Giuseppe Guerini (Polti) @ 6min 51sec

- Oscar Camenzind (Mapei) @ 12min 16sec

- Daniel Clavero (Vitalicio Seguros) @ 18min 4sec

- Gianni Faresin (Mapei) @ 18min 31sec

- Paolo Bettini (ASICS) @ 21min 3sec

- Daniele De Paoli (Ros Mary-Amica Chips) @ 21min 35sec

- Paolo Savoldelli (Saeco) @ 25min 54sec

- Serguei Gontchar (Cantina Tollo) @ 25min 58sec

- Massimo Podenzana (Mercatone Uno) @ 28min 22sec

- José Jaime Gonzales (Kelme) @ 29min 24sec

- Luis Rubiera (Kelme) @ 31min 25sec

- Alex Zülle (Festina) @ 33min 26sec

- Andrea Noè (ASICS) @ 34min 29sec

- Leonardo Piepoli (Saeco) @ 35min 56sec

- Claus-Michael Möller (TVM) @ 39min 22sec

- Paolo Lanfranchi (Mapei) @ 40min 6sec

- Roberto Sgambelluri (Brescialat) @ 40min 33sec

- Marco Velo (Mercatone Uno) @ 40min 53sec

- Stefano Garzelli (Mercatone Uno) @ 41min 28sec

- Stefano Faustini (Vini Caldirola) @ 41min 33sec

- Vladislav Bobrik (Riso Scotti-MG) @ 41min 53sec

- Francesco Secchiari (Scrigno-Gaerne) @ 42min 28sec

- Wladimir Belli (Festina) @ 42min 48sec

- Fabrice Gougot (Casino) @ 44min 41sec

- Hernan Buenahora (Vitalicio Serguros) @ 47min 26sec

- Laurent Roux (TVM-Farm Frites) @ 49min 14sec

- Roberto Conti (Mercatone Uno) @ 50min 28sec

- Davide Rebellin (Polti) @ 50min 48sec

- Marco Magnani (Cantina Tollo) @ 51mn 17sec

- Massimo Codol (Mapei) @ 54min 26sec

- Amilcare Tronca (Ballan) @ 57min 25sec

- Luc Leblanc (Polti) @ 58min 41sec

- Mariano Piccoli (Brescialat) @ 1min 1min 33sec

- Pavel Padrnos (Saeco) @ 1hr 3min 9sec

- Felix Manuel Garcia (Festina) @ 1min 4min 25sec

- Niklas Axelsson (Scrigno-Gaerne) @ 1hr 5min 28sec

- Felice Puttini (Ros Mary-Amica Chips) @ 1hr 9min 0sec

- Piotr Ugrumov (Ballan) @ 1hr 9min 24sec

- Gabriele Missaglia (Mapei) @ 1hr 9min 25sec

- Dario Frigo (Saeco) @ 1hr 9min 38sec

- Marcello Siboni (Mercatone Uno) @ 1hr 12min 21sec

- Aleksandr Shefer (Asics) @ 1hr 13min 31sec

- Juan Carlos Dominguez (Vitalicio Seguros) @ 1hr 15min 43sec

- Nicola Loda (Ballan) @ 1hr 23min 51sec

- Leonardo Calzavara (Vini Caldirola) @ 1hr 24min 3sec

- Armin Meier (Festina) @ 1hr 26min 4sec

- Fabian Jeker (Festina) @ 1hr 30min 5sec

- Gianni Bugno (Mapei) @ 1hr 35min 0sec

- Dimitri Konyshev (Mercatone Uno) @ 1hr 35min 6sec

- Gabriele Colombo (Ballan) @ 1hr 35min 35sec

- Andrei Kivilev (Festina) @ 1hr 36min 22sec

- Santiago Botero (Kelme-Costa Blanca) @ 1hr 36min 56sec

- Arsenio Gonzalez (Kelme-Costa BLanca) @ 1hr 42min 23sec

- Mauro Zanetti (Vini Caldirola) @ 1hr 44min 39sec

- Bruno Cenghialta (Riso Scotti-MG) @ 1hr 47min 13sec

- Gilberto Simoni (Cantina Tollo) @ 1hr 47min 49sec

- Vicente Aparicio (Vitalicio Seguros) @ 1hr 48min 52sec

- Claudio Chiappucci (Ros Mary-Amica Chips) @ 1hr 49min 17sec

- Mauro Scirea (Saeco) @ 1hr 51min 51sec

- Giorgio Furlan (Vini Caldirola) @ 1hr 56min 10sec

- Federico Profeti (Amore & Vita) @ 2hr 0min 24sec

- Andrea Ferrigato (Vitalicio Seguros) @ 2hr 2min 10sec

- Carlo Finco (Ballan) @ 2hr 5min 6sec

- Mirko Gualdi (Polti) @ 2hr 6min 6sec

- Stefano Cattai (Ballan) @ 2hr 7min 3sec

- Davide Bramati (Mapei) @ 2hr 8min 34sec

- Ermanno Brignoli (Riso Scotti-MG) @ 2hr 10min 8sec

- Marco Serpellini (Brescialat) @ 2hr 10min 33sec

- Filippo Casagrande (Scrigno-Gaerne) @ 2hr 10min 44sec

- Zbigniew Spruch (Mapei) @ 2hr 12min 37sec

- Luca Mazzanti (Cantina Tollo) @ 2hr 13min 1sec

- Maurizio De Pasquale (Amore & Vita) @ 2hr 13min 1sec

- Michele Coppolillo (Asics) @ 2hr 13min 48sec

- Luca Gelfi (Ros Mary-Amica Chips) @ 2hr 13min 52sec

- Gian-Matteo Fagnini (Saeco) @ 2hr 13min 58sec

- Angelo Canzonieri (Ballan) @ 2hr 14min 15sec

- Frédéric Bessy (Casino) @ 2hr 15min 24sec

- Marzio Bruseghin (Brescialat) @ 2hr 24min 16sec

- Andrea Patuelli (Amore & Vita) @ 2hr 25min 44sec

- Stefano Finesso (Ros Mary-Amica Chips) @ 2hr 28min 53sec

- Marco Della Vedova (Brescialat) @ 2hr 31min 37sec

- David Lefèvre (Casino) @ 2hr 32min 0sec

- Rolf Jaermann (Casino) @ 2hr 32min 49sec

- Andrea Brognara (Riso Scotti-MG) @ 2hr 39min 59sec

- Andrea Vatteroni (Scrigno-Gaerne) @ 2hr 42min 59sec

- Martin Hvastija (Cantina Tollo) @ 2hr 45min 19sec

- David Tani (Asics) @ 2hr 50min 30sec

- Vladimir Duma (Scrigno-Gaerne) @ 2hr 55min 52sec

- Massimo Strazzer (Cantina Tollo) @ 3hr 7min 18sec

- Marco Saligari (Casino) @ 3hr 9min 15sec

- Giuseppe Calcaterra (Saeco) @ 3hr 9min 55sec

- Marco-Antonio Di Renzo (Cantina Tollo) @ 3hr 14min 8sec

Points Classification:

Mariano Piccoli (Brescialat): 194 points

Mariano Piccoli (Brescialat): 194 points- Marco Pantani (Mercatone Uno): 158

- Gian Matteo Fagnini (Saeco): 156

- Pavel Tonkov (Mapei): 140

- Alex Zülle (Festina): 117

Climbers' Competition:

Marco Pantani (Mercatone Uno): 89 points

Marco Pantani (Mercatone Uno): 89 points- José Jaime Gonzalez (Kelme-Costa Blanca): 63

- Pavel Tonkov (Mapei): 43

- Alex Zülle (Festina): 37

- Paolo Bettini (Asics): 30

Intergiro:

Gian Matteo Fagnini (Saeco): 62hr 32min 12sec

Gian Matteo Fagnini (Saeco): 62hr 32min 12sec- Mariano Piccoli (Brescialat) @ 55sec

- Nicola Loda (Ballan) @ 2min 29sec

- Serguei Gontchar (Cantina Tollo)

- Volodimir Duma (Scrigno-Gaerne)

Team Classification (time):

- Mapei: 296hr 17min 54sec

- Mercatone Uno @ 17min 11sec

- Saeco @ 50min 22sec

- Polti @ 1hr 5min 41sec

- Vitalicio Seguros @ 1hr 10min 45sec

Team Classificaton (points):

- Polti: 479 points

- Mapei: 469

- Mercatone Uno: 381

- Asics: 381

- Saeco: 325

1998 Giro stage results with running GC:

Saturday, May 16: Prologue, Nice (France) 7 km individual time trial (cronometro)

- Alex Zülle: 7min 55sec

- Serguei Gontchar @ 1sec

- Arturas Kasputis @ 10sec

- Marco Velo @ 13sec

- Toni Tauler @ 14sec

- Massimo Podenzana @ 16sec

- Fabiano Fontanelli @ 17sec

- Juan Carlos Dominguez s.t.

- Carlo Finco @ 18sec

- Gabriele Colombo s.t.

Sunday, May 17: Stage 1, Nice (France) - Cuneo, 162 km

![]() Major ascent: Colle di Tende

Major ascent: Colle di Tende

- Mariano Piccoli: 3hr 55min 39sec

- Michele Bartoli s.t.

- Fabrizio Guidi s.t.

- Angel Edo s.t.

- Nicola Minali s.t.

- Mario Cipollini s.t.

- Endrio Leoni s.t.

- Francesco Arazzi s.t.

- Fabio Baldato s.t.

- Fabio Fontanelli s.t.

GC after Stage 1:

- Alex Zülle: 4hr 3min 34sec

- Serguei Gontchar @ 1sec

- Arturas Kasputis @ 10sec

- Michele Bartoli @ 12sec

- Marco Velo @ 13sec

- Toni Tauler @ 14sec

- Massimo Podenzana @ 16sec

- Fabiano Fontanelli @ 17sec

- Juan Carlos Dominguez s.t.

- Carlo Finco @ 18sec

Monday, May 18: Stage 2, Alba - Imperia, 160 km

![]() Major ascents: Colle San Bernardo, Capo Berta

Major ascents: Colle San Bernardo, Capo Berta

- Angel Edo: 3hr 53min 23sec

- Mariano Piccoli s.t.

- Nicola Loda s.t.

- Michele Bartoli s.t.

- Gian-Matteo Fagnini s.t.

- Wladimir Belli s.t.

- Fabio Baldato s.t.

- Gabriele Missaglia s.t.

- Davide Rebellin

- Glenn Magnusson s.t.

GC after Stage 2:

- Alex Zülle: 7hr 56min 57sec

- Serguei Gontchar @ 1sec

- Michele Bartoli @ 10sec

- Mariano Piccoli @ 13sec

- Marco Velo s.t.

- Massimo Podenzana @ 16sec

- Juan Carlos Domiguez @ 17sec

- Gabriele Colombo @ 18sec

- José Enrique Gutierrez s.t.

- Riccardo Forconi @ 19sec

Tuesday, May 19: Stage 3, Rapallo - Forte dei Marmi, 196 km

![]() Major ascent: Passo del Bracco

Major ascent: Passo del Bracco

- Nicola Minali: 4hr 44min 34sec

- Massimo Strazzer s.t.

- Francesco Arazzi s.t.

- Alessandro Petacchi s.t.

- Silvio Martinello s.t.

- Giancarlo Raimondi s.t.

- Federico Colonna s.t.

- Glen Magnusson s.t.

- Jeroen Blijlevens s.t.

- Zbigniew Spruch s.t.

GC after Stage 3:

- Serguei Gontchar: 12hr 41min 32sec

- Michele Bartoli @ 9sec

- Mariano Piccoli @ 12sec

- Marco Velo s.t.

- Alex Zülle s.t.

- Juan Carlos Dominguez @ 16sec

- José Enrique Dominguez @ 16sec

- Riccardo Forconi @ 18sec

- Oskar Camenzind @ 20sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 22sec

Wednesday, May 20: Stage 4, Viareggio - Monte Argentario, 239 km

![]() Major ascent: Poggio Fondoni

Major ascent: Poggio Fondoni

- Nicola Miceli: 6hr 15min 29sec

- Michele Bartoli @ 3sec

- Mariano Piccoli s.t.

- Angel Edo s.t.

- Fabio Baldato s.t.

- Davide Rebellin s.t.

- Luca Mazzanti s.t.

- Alessandro Petacchi s.t.

- Endrio Leoni s.t.

- Bruno Cenghialta s.t.

GC after Stage 4:

- Serguei Gontchar: 18hr 57min 4sec

- Michele Bartoli @ 1sec

- Mariano Piccoli @ 8sec

- Marco Velo @ 12sec

- Alex Zülle s.t.

- Juan Carlos Dominguez @ 16sec

- José Enrique Gutierrez @ 17sec

- Riccardo Forconi @ 18sec

- Oskar Camenzind @ 20sec

- PAvel Tonkov @ 22sec

Thursday, May 21: Stage 5, Ortabello - Frascati, 206 km

- Mario Cipollini: 4hr 44min 25sec

- Silvio Martinello s.t.

- Serguei Smetanine s.t.

- Fabio Baldato s.t.

- Michele Bartoli s.t.

- Luca Mazzanti s.t.

- Nicola Loda s.t.

- Angel Edo s.t.

- Gabriele Missaglia s.t.

- Zbigniew Spruch s.t.

GC after Stage 5:

- Michele Bartoli: 23hr 41min 26sec

- Serguei Gontchar @ 3sec

- Mariano Piccoli @ 11sec

- Marco Velo @ 15sec

- Alex Zülle s.t.

- Juan Carlos Dominguez @ 19sec

- José Enrique Gutierrez @ 20sec

- Riccardo Forconi @ 21sec

- Oskar Camenzind @ 23sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 25sec

Friday, May 22: Stage 6, Maddaloni - Lago Laceno, 160 km

![]() Major Ascents: Monte Taburno, Piano di Verteglia, Valico Villagio Laceno

Major Ascents: Monte Taburno, Piano di Verteglia, Valico Villagio Laceno

- Alex Zülle: 4hr 21min 43sec

- Michele Bartoli @ 24sec

- Luc Leblanc s.t.

- Marco Pantani s.t.

- Davide Rebellin @ 34sec

- Wladimir Belli s.t.

- Nicola Miceli s.t.

- Giuseppe Guerini s.t.

- Enrico Zaina s.t.

- Dario Frigo s.t.

- Ivan Gotti s.t.

- Pavel Tonkov s.t.

- Paolo Savoldelli s.t.

- Stefano Garzelli @ 1min 15sec

- Laurent Roux s.t.

GC after Stage 6:

- Alex Zülle: 28hr 3min 12sec

- Michele Bartoli @ 13sec

- Luc Leblanc @ 50sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 56sec

- Paolo Savoldelli @ 57sec

- Marco Pantani @ 1min 2sec

- Nicola Miceli @ 1min 3sec

- Dario Frigo @ 1mn 4sec

- Ivan Gotti s.t.

- Enrico Zaina @ 1min 8sec

Saturday, May 23: Stage 7, Montella - Matera, 235 km

![]() Major ascents: Nusco, Valico Romito, Matera

Major ascents: Nusco, Valico Romito, Matera

- Mario Cipollini: 6hr 30min 0sec. 36.15 km/hr

- Fabio Baldato s.t.

- Angel Edo s.t.

- Glenn Magnusson s.t.

- Michele Bartoli s.t.

- Endrio Leoni s.t.

- Enrico Cassani s.t.

- Serguei Smetanine s.t.

- Andrei Kivilev s.t.

- Mariano Piccoli s.t.

GC after Stage 7:

- Alex Zülle: 34hr 33min 12sec

- Michele Bartoli @ 11sec

- Luc Leblanc @ 50sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 56sec

- Paolo Savoldelli @ 57sec

- Marco Pantani @ 1min 2sec

- Nicola Miceli @ 1min 3sec

- Dario Frigo @ 1min 4sec

- Ivan Gotti s.t.

- Enrico Zaina @ 1min 8sec

Sunday, May 24: Stage 8, Matera - Lecce, 191 km

![]() Ascent: Montescaglioso

Ascent: Montescaglioso

- Mario Cipollini: 5hr 8min 47sec. 37.11 km/hr

- Silvio Martinello s.t.

- Endrio Leoni s.t.

- Francesco Arazzi s.t.

- Alessandro Petacchi s.t.

- Massimo Strazzer s.t.

- Nicola Loda s.t.

- Angel Edo s.t.

- Federico Colonna s.t.

- Marco Zanotti s.t.

GC after Stage 8

- Alex Zülle: 39hr 41min 59sec

- Michele Bartoli @ 5sec

- Luc Leblanc @ 50sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 56sec

- Paolo Savoldelli @ 57sec

- Marco Pantani @ 1min 2sec

- Nicola Miceli @ 1mn 3sec

- Ivan Gotti @ 1min 4sec

- Dario Frigo s.t.

- Enrico Zaina @ 1min 8sec

Monday, May 25: Stage 9, Foggia - Vasto, 169 km

![]() Ascent: San Giovanni Rotondo

Ascent: San Giovanni Rotondo

- Glenn Magnusson: 3hr 55min 43sec. 43.018 km/hr

- Silvio Martinello s.t.

- Mario Cipollini s.t.

- Zbigniew Spruch s.t.

- Fabiano Fontanelli s.t.

- Endrio Leoni s.t.

- Geert van Bondt s.t.

- Michele Bartoli s.t.

- Alessandro petacchi s.t.

- Mariano Piccoli s.t.

GC after Stage 9:

- Alex Zülle: 43hr 37min 42sec

- Michele Bartoli @ 5sec

- Luc Leblanc @ 50sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 56sec

- Paolo Savoldelli @ 57sec

- Marco Pantani @ 1min 2sec

- Nicola Miceli @ 1min 3sec

- Ivan Gotti @ 1min 4sec

- Dario Frigo s.t.

- Enrico Zaina @ 1min 8sec

Tuesday, May 26: Stage 10, Vasto - Macerata, 212 km

- Mario Cipollini: 5hr 10min 43sec

- Silvio Martinello s.t.

- Endrio Leoni s.t.

- Francesco Arazzi s.t.

- Fabio Baldato s.t.

- Alessandro Petacchi s.t.

- Federico Colonna s.t.

- Biagio Conte s.t.

- Fabiano Fontanelli s.t.

- Angel Edo s.t.

GC after Stage 10:

- Alex Zülle: 48hr 48min 25sec

- Michele Bartoli @ 5sec

- Luc Leblanc @ 50sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 56sec

- Paolo Savoldelli @ 57sec

- Marco Pantani @ 1min 2sec

- Nicola Miceli @ 1min 3sec

- Ivan Gotti @ 1min 4sec

- Dario Frigo s.t.

- Enrico Zaina @ 1min 8sec

Wednesday, May 27: Stage 11, Macerata - San Marino, 214 km

![]() Major ascent: San Marino

Major ascent: San Marino

- Andrea Noè: 5hr 12min 20sec

- Marco Pantani @ 7sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 10sec

- Davide Rebellin s.t.

- Ivan Gotti s.t.

- Michele Bartoli s.t.

- Alex Zülle s.t.

- Luc Leblanc s.t.

- Laurent Roux s.t.

- Giuseppe Guerini s.t.

GC after Stage 11:

- Alex Zülle: 54hr 0min 55sec

- Michele Bartoli @ 5sec

- Luc LeBlanc @ 50sec

- Marco Pantani @ 51sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 52sec

- Nicola Miceli @ 1min 3sec

- Ivan Gotti @ 1min 4sec

- Dario Frigo s.t.

- Enrico Zaina @ 1min 8sec

- Giuseppe Guerini @ 1min 10sec

Thursday, May 28: Stage 12, San Marino - Carpi, 202 km

- Laurent Roux: 4hr 37min 8sec

- Serguei Smetanine s.t.

- Germano Pierdomenico @ 2sec

- Martin Hvastija @ 6sec

- Paolo Lanfranchi s.t.

- Fabrizio Guidi s.t.

- Andrei Zintchenko s.t.

- Rolf Jaermann s.t.

- José Luis Rubeira s.t.

- Miguel Angel Martin Perdiguero @ 42sec

GC after Stage 12:

- Laurent Roux: 58hr 39min 50sec

- Andrea Noè @ 19sec

- Alex Zülle @ 35sec

- Michele Bartoli @ 40sec

- Andrei Zintchenko @ 42sec

- Oskar Camenzind @ 43sec

- José Luis Rubiera @ 49sec

- Paolo Lanfranchi @ 1min 11sec

- Luc Leblanc @ 1min 25sec

- Marco Panani @ 1min 26sec

Friday, May 29: Stage 13, Carpi - Schio, 166 km

![]() Ascent: Zovo

Ascent: Zovo

- Michele Bartoli: 3hr 58min 2sec

- Giuseppe Guerini s.t.

- Paolo Bettini s.t.

- Andrea Noè @ 3sec

- Davide Rebellin @ 16sec

- José Luis Rubiera s.t.

- Nicola Miceli s.t.

- Juan Carlos Domnguez s.t.

- Oskar Camenzind s.t.

- Luc Leblanc s.t.

GC after Stage 13:

- Andrea Noè: 62hr 38min 14sec

- Michele Bartoli @ 6sec

- Alex Zülle @ 37sec

- Oskar Canenzind s.t.

- José Luis Rubiera @ 43sec

- Laurent Roux @ 49sec

- Giuseppe Guerini @ 1min 15sec

- Luc Leblanc @ 1min 19sec

- Marco Pantani @ 1min 20sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 1min 21sec

Saturday, May 30: Stage 14, Schio - Piancavallo, 165 km

![]() Major ascent: Piancavallo

Major ascent: Piancavallo

- Marco Pantani: 4hr 22min 11sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 13sec

- Alex Zülle s.t.

- Giuseppe Guerini @ 28sec

- Andrea Noè @ 1min 51sec

- Juan Carlos Dominguez @ 2min 2sec

- Marco Velo s.t.

- Daniele De Paoli s.t.

- Daniel Clavero s.t.

- Riccardo Forconi s.t.

GC after Stage 14:

- Alex Zülle: 67hr 1min 11sec

- Marco Pantani @ 22sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 40sec

- Giuseppe Guerini @ 57sec

- Andrea Noè @ 1mn 5sec

- Michele Bartoli @ 2min 41sec

- Oskar Camenzind @ 2min 49sec

- Laurent Roux @ 3min 1sec

- Wladimir Belli @ 3min 22sec

- Luc Leblanc @ 3min 31sec

Sunday, May 31: Stage 15, Trieste 40 km individual time trial (cronometro)

![]() Ascent: Prosecco

Ascent: Prosecco

- Alex Zülle: 44min 38sec

- Serguei Gontchar @ 53sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 1min 22sec

- Juan Carlos Dominguez @ 2min 0sec

- Michele Bartoli @ 2min 11sec

- Bruno Boscardin @ 2min 13sec

- Riccardo Forconi @ 2min 16sec

- Oskar Camenzind @ 2min 32sec

- Paolo Savoldelli @ 2min 33sec

- Arturas Kasputis @ 2min 44sec

- Marco Pantani @ 3min 26sec

GC after Stage 15:

- Alex Zülle: 67hr 45min 49sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 2min 2sec

- Marco Pantani @ 3min 48sec

- Giuseppe Guerini @ 4min 21sec

- Andrea Noè @ 4min 34sec

- Michele Bartoli @ 4min 52sec

- Oskar Camenzind @ 5min 21sec

- Serguei Gontchar @ 5min 48sec

- Juan Carlos Dominguez @ 5min 50sec

- Riccardo Forconi @ 6min 15sec

Monday, June 1: Stage 16, Udine - Asiago, 236 km

![]() Major ascent: Tortima

Major ascent: Tortima

- Fabiano Fontanelli: 5hr 53min 53sec

- Paolo Bettini s.t.

- Mario Scirea s.t.

- Mariano Piccoli @ 7sec

- Andrea Ferrigato s.t.

- Nicola Lodas.t.

- Enrico Cassani s.t.

- Javier Otxoa s.t.

- Claus-Michael Möller @ 13sec

- Fabrizio Guidi @ 3min 11sec

GC after Stage 16:

- Alex Zülle: 73hr 51min 28sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 2min 2sec

- Paolo Bettini @ 3min 29sec

- Marco Pantani @ 3min 48sec

- Giuseppe Guerini @ 4min21sec

- Andrea Noè @ 4min 34sec

- Michele Bartoli @ 4min 52sec

- Oskar Camenzind @ 5min 31sec

- Serguei Gontchar @ 5min 48sec

- Juan Carlos Dominguez @ 5min 50sec

Tuesday, June 2: Stage 17, Asiago - Selva di Val Gardena, 215 km

![]() Major ascents: Passo Duran, Forcella Staulanza, Passo di Fedaia, Passo di Sella

Major ascents: Passo Duran, Forcella Staulanza, Passo di Fedaia, Passo di Sella

- Giuseppe Guerini: 6hr 16min 58sec

- Marco Pantani s.t.

- José Jaime Gonzalez @ 2min 4sec

- Pavel Tonkov s.t.

- Oskar Camenzind @ 2min 18sec

- Nicola Miceli @ 3min 3sec

- Daniele De Paoli 2 3min 25sec

- Stefano Garzelli @ 4min 37sec

- Alex Zülle s.t.

- Daniel Clavero s.t.

GC after Stage 17:

- Marco Pantani: 80hr 12min 2sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 30sec

- Giuseppe Guerini @ 31sec

- Alex Zülle @ 1min 1sec

- Oskar Camenzind @ 4min 13sec

- Nicola Miceli @ 7min 18sec

- Riccardo Forconi @ 9min 2sec

- Daniel Clavero @ 9min 35sec

- Serguei Gontchar @ 9min 36sec

- Wladimir Belli @ 10min 22sec

Wednesday, June 3: Stage 18, Selva di Val Gardena - Alpe di Pampeago, 115 km

![]() Major ascents: San Floriano, Passo di Lavazè, Alpe di Pampeago

Major ascents: San Floriano, Passo di Lavazè, Alpe di Pampeago

- Pavel Tonkov: 3hr 36min 53sec. 31.8 km/hr

- Marco Pantani @ 1sec

- Nicola Miceli @ 44sec

- Alex Zülle @ 58sec

- Giuseppe Guerini @ 1min 7sec

- Oskar Camenzind @ 1min 15sec

- Paolo Bettini @ 2min 0sec

- Daniel Clavero @ 2min 15sec

- Andrea Noè s.t.

- Francesco Secchiari @ 2min 21sec

GC after Stage 18:

- Marco Pantani: 83hr 48min 46sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 27sec

- Giuseppe Guerini @ 1min 47sec

- Alex Zülle @ 2min 8sec

- Oskar Cemenzind @ 5min 37sec

- Nicola Miceli @ 8min 7sec

- Daniel Clavero @ 11min 59sec

- Paolo Bettini @ 13min 10sec

- José Luis Rubiera @ 13min 23sec

- Serguei Gontchar @ 15min 28sec

Thursday, June 4: Stage 19, Cavalese - Plan di Montecampione, 243 km

![]() Major ascents: Fai della Paganella, Goletto di Cadino, Plan di Montecampione

Major ascents: Fai della Paganella, Goletto di Cadino, Plan di Montecampione

- Marco Pantani: 7hr 42min 52sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 57sec

- Giuseppe Guerini @ 3min 16sec

- Francesco Secchiari @ 4min 4sec

- Daniel Clavero s.t.

- Daniele De Paoli @ 4min 16sec

- Oskar Camenzind @ 5min 43sec

- Nicola Miceli @ 5min 44sec

- José Jaime Gonzalez @ 5min 46sec

- Paolo Bettini @ 5min 48sec

GC after Stage 19:

- Marco Pantani: 91hr 31min 26sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 1min 28sec

- Giuseppe Guerini @ 5min 11sec

- Oskar Camenzind @ 11min 32sec

- Nicola Miceli @ 14min 23sec

- Daniel Clavero @ 16min 15sec

- Paolo Bettini @ 19min 10sec

- Gianni Faresin @ 24min 17sec

- Daniele De Paoli @ 26min 1sec

- Serguei Gontchar @ 26min 28sec

Friday, June 5: Stage 20, Boario Terme - Mendrisio (Switzerland), 143 km

![]() Ascent: Colle del Gallo

Ascent: Colle del Gallo

- Gian-Matteo Fagnini: 3hr 31min 33sec. 40.6 km/hr

- Mariano Piccoli s.t.

- Wladimir Belli s.t.

- Gabriele Colombo s.t.

- Davide Rebellin s.t.

- Aleksandr Shefer s.t.

- Felice Puttini s.t.

- Federico Profeti s.t.

- Paolo Lanfranchi s.t.

- Daniele De Paoli s.t.

GC after Stage 20:

- Marco Pantani: 95hr 10min 15sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 1min 28sec

- Giuseppe Guerini @ 5min 11sec

- Oskar Camenzind @ 11min 32sec

- Nicola Miceli @ 14min 23sec

- Daniel Clavero @ 16min 15sec

- Gianni Faresin @ 16min 57sec

- Daniele De Paoli @ 18min 41sec

- Paolo Bettini @ 19min 10sec

- Paolo Savoldelli @ 25min 9sec

Saturday, June 6: Stage 21, Mendrisio (Switzerland) - Lugano (Switzerland) 34 km individual time trial (cronometro)

Nicola Miceli and Riccardo Forconi had hematocrits above the allowed 50% and were not allowed to start the time trial.

- Serguei Gontchar: 39min 54sec

- Massimo Podenzana @ 29sec

- Marco Pantani @ 30sec

- Marco Velo @ 31sec

- PAvel Tonkov @ 35sec

- Marco Serpellini @ 1min 1sec

- Oskar Camenzind @ 1mn 14sec

- Paolo Savoldelli @ 1min 15sec

- Alex Zülle @ 1min 32sec

- Claus-Michael Möller @ 1min 40sec

GC after Stage 21:

- Marco Pantani: 95hr 50min 39sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 1min 33sec

- Giuseppe Guerini @ 6min 51sec

- Oskar Camenzind @ 12min 16sec

- Daniel CLavero @ 18min 4sec

- Gianni Faresin @ !8min 31sec

- Paolo Bettini @ 21min 3sec

- Daniele De Paoli @ 21min 35sec

- Paolo Savoldelli @ 25min 54sec

- Serguei Gontchar @ 25min 58sec

Sunday, June 7: 22nd and Final Stage, Lugano (Switzerland) - Milano, 72km

Because of bad weather, the stage was shortened from its planned 102 km

![]() Ascent: Brinzio

Ascent: Brinzio

- Gian-Matteo Fagnini: 2hr 57min 53sec

- Massimi Strazzer s.t.

- Zbigniew Spruch s.t.

- José Luis Rubiera

- Mariano Piccoli s.t.

- Mirko Gualdi s.t.

- Nicola Loda s.t.

- Luca Mazzanti s.t.

- Martin Hvastija s.t.

- Marco Serpellini s.t.

The Story of the 1998 Giro d'Italia

This excerpt is from "The Story of the Giro d'Italia", Volume 2. If you enjoy it we hope you will consider purchasing the book, either print eBook or Audiobook. The Amazon link here will make the purchase easy.

There seemed to be a consensus among a wide range of racers, managers and writers as to who was most likely to win the 1998 Giro. Alex Zülle, who had left the Spanish ONCE squad for the powerful Festina team, was the man to beat. He was an outstanding time trialist and the 80 kilometers of racing against the clock in the 1998 Giro certainly played to his strength. Gotti thought Zülle had a built-in four-minute advantage over the climbers that would have to be overcome in the high mountains. Easier said than done, because Zülle was also an excellent climber and capable Grand Tour rider, having won the 1996 and ’97 Vueltas.Others proposed the last two winners, Gotti and Tonkov. Only a couple of experts thought Marco Pantani could prevail on what was said to be a time trialist’s parcours.

Zülle certainly lived up to expectations when he won the 7-kilometer prologue on a rainy day in Nice (the sixth time the Giro had started in a foreign country). The Swiss rider had the maglia rosa by 1 second over Serguei Gontchar.

The first stage returned the Giro to its home country with what was expected to be a sprint finish in Cuneo. Cipollini’s lead-out train was late getting organized and two of his Saeco teammates went down as the peloton wound its way around the traffic circles. The loss of momentum was perfect for a clever and strong opportunist to try to slip away in the last kilometer. Mariano Piccoli’s burglary in plain sight was perfectly executed. Piccoli got the stage while Zülle remained the leader.

Going from Cuneo to Imperia on the Italian Riviera with the Capo Berta ascent coming just five kilometers from the end, stage two’s racing said this Giro was going to be a fight from the very beginning. Before the Capo Berta started to rise, Pantani sent his entire team to the front to bring up the pace. As the road rose, Paolo Bettini leaped out of the field with Pantani hot on his tail. Soon Michele Bartoli clawed his way to the duo. Bettini couldn’t take his fellow escapees’ supersonic speed and sat up, but Bartoli and Pantani screamed up the hill. Back in the pack, this was a four-alarm fire and the peloton strung itself out over the hill, desperate to retrieve the two gifted racers. Near the summit the catch was made and Zülle’s lead was preserved.

The next day Zülle lost the Pink Jersey when he was caught behind a crash (not unusual for Zülle) near the finish, giving the Pink Jersey to Serguei Gontchar.

Again Bartoli and Pantani slapped the field around a bit. The last six kilometers of the fourth stage had a rugged sawtooth profile where Bartoli tried to get away. He was instantly marked by Pantani and Enrico Zaina. This trio could not be allowed any freedom and were painfully pulled back. Both Pantani and Bartoli were racing the Giro as if each day were a one-day Classic, not worrying about saving energy for later. After the big guns were caught, Nicola Miceli took advantage of that moment of relaxation that almost always occurs after breaks are caught and scooted off for the stage win. Bartoli, having a seemingly endless well of energy, took second, and with the attendant time bonus was 1 second short of becoming the Giro’s leader.

Still headed south, the Giro had passed through Tuscany and was now rolling by Rome to the stage five finish in Frascati. At ten kilometers to go it looked like a typical Saeco lead-out-train finish with nearly all of Cipollini’s team at the front, but by the final kilometer he had only one teammate left. It didn’t matter. Cipollini led the sprint out himself, riding the final 200 meters on the brake levers with no one able to come around the powerful Tuscan. Bartoli had managed to gain some bonus seconds in the intermediate sprints and was now the Pink Jersey.

As the Giro rolled into Campania with its stage six finish at Lago Laceno, three rated climbs confronted the riders. Things were still together by the time they reached the final hill, the Valico Villagio-Laceno, with its short stretch of 21-percent gradient. When the peloton reached that steep part, Bartoli did a sharp attack that caught Pantani’s attention. Pantani closed up to Bartoli and not being content with Bartoli’s speed, ratcheted up the pace. Alert to the danger, Gotti and several others moved up to Pantani. He looked back and went still faster and then he was gone. Or was he? This day Pantani didn’t appear to have his normal sharp climbing snap and first Bartoli went after him and was able to keep the small climber in sight. Then Luc Leblanc and finally Zülle were able to latch onto Bartoli.

Zülle lit the jets, gunning for and catching Pantani, but he wasn’t content. He put in another dig and Pantani was able to stay with him for a few hundred meters, but Zülle was on fire. Even Pantani couldn’t hold his wheel that day and he went over the crest of the hill eight seconds behind the Swiss superman. The final three kilometers were on flat road, happy hunting grounds for one of the world’s foremost time trialists. Zülle extended his lead, won the stage and retook the maglia rosa. Bartoli, Leblanc and Pantani followed in 24 seconds later.

The General Classification now:

1. Alex Zülle

2. Michele Bartoli @ 13 seconds

3. Luc Leblanc @ 50 seconds

4. Pavel Tonkov @ 56 seconds

5. Paolo Savoldelli @ 57 seconds

6. Marco Pantani @ 1 minute 2 seconds

By the stage eight finish in Lecce, the 1998 Giro’s southernmost point, the General Classification hadn’t changed. The race turned north and headed for the Dolomites and the Alps. The route followed the Adriatic shoreline, making flat stages for the sprinters. Cipollini’s win in Macerata in Le Marche was his 25th, tying Eddy Merckx’s postwar Giro stage-win record. Although Bartoli had managed to take a few bonus seconds in sprints, there was still no change to the General Classification.

Stage eleven’s climb to San Marino was the real start of the Giro. At the sign of the day’s first gradient, José “Chepe” González decided to go for a long, lonesome ride. Andrea Noè initially spoiled his plans, but González was able to temporarily drop the Italian.

Back in the peloton, Pantani’s Mercatone Uno team massed at the front. San Marino was Mercatone Uno’s hometown, giving the team extra motivation for a stage win. As the road got ever steeper, Pantani attacked again and again. His relentless accelerations kept thinning the herd but there were tenacious contenders who were determined to stay with the Pirate. Up ahead, González had run out of gas. Noè, who was unhappy with the little Colombian’s refusal to work with him, steamed right on by.

Tenacity wasn’t enough. With a kilometer to go Pantani was able to get away from his followers and had Noè in his sights, but at the end of the stage still lacked 7 seconds to catch the fleeing Italian.

The General Classification:

1. Alex Zülle

2. Michele Bartoli @ 5 seconds

3. Luc Leblanc @ 50 seconds

4. Marco Pantani @ 51 seconds

5. Pavel Tonkov @ 52 seconds

The next stage, coming down from San Marino, was on a wet, sloppy day, perfect for letting a break of non-threatening riders get away. Laurent Roux, the best placed of the fuga di bidone, lifted himself into pink.

The Giro had departed from the warmth of southern Italy. Stage thirteen was cold and wet. To warm them a bit, the riders were to cross the 650-meter high Passo dello Zovo, which crested a few kilometers before the finish. After two weeks of racing, Pantani's form had markedly improved and the new, improved Pirate bludgeoned the pack, landing blow after blow until they had to let him go. Zülle got up to him as did Bartoli, and at the top it was Pantani, Zülle and Tonkov.

On the descent Pantani flew down the wet roads fearlessly. On one curve he pushed his bike too hard and went sliding across the road, taking Zülle with him. In a flash they were both up, but not before a few riders had passed them. Zülle, a powerful but somewhat unskilled and crash-prone bike handler, almost went off the road at least one more time as did Tonkov. The Russian, not wanting to trade his skin for a few seconds, let Bartoli and several others go on ahead. At the bottom of the hill a group of four coalesced: Bartoli, Bettini, Giuseppe Guerini and Andrea Noè. Bartoli grabbed the stage win and the 12 precious bonus seconds. Pantani’s group came in 16 seconds later and Zülle’s was about another 6 seconds behind them. Noè was back in pink, Bartoli was second and Zülle had lost some valuable time to Pantani, who was turning out to be a relentlessly aggressive foe.

Now for the real mountains. Stage fourteen was a 165-kilometer trip to a finish atop Piancavallo, a nearly 1,300-meter-high, fifteen-kilometer long climb. Early on the ascent, the only one this stage, Bartoli took a long, out of the saddle, big-gear pull. That strung things out. He looked around for his teammate Andrea Noè and saw that Noè couldn’t follow the pace, so he shut it down.

That didn’t slow things down a bit, because just as Bartoli was looking around, he was swallowed up by Pantani’s teammates, especially Stefano Garzelli, who initiated what looked like a ruinous pace. Zülle and Tonkov, knowing that Pantani was setting things up for a hammer blow, stayed glued to his wheel.

After each of his gregari had taken his last pull, Pantani took wing and only Tonkov, as usual with misery written all over his face, was able to hold his wheel. Soon even Tonkov had to let the Pirate go. Further back Zülle was now matching Pantani’s speed. Noè, looking ghastly, was gone and Ivan Gotti, the previous year’s winner, was quickly shown the back door.

Gotti said he had been unable to find any sort of competitive form this year and was completely out of contention after only a couple of kilometers of climbing.

Pantani was back! He won his first Giro stage in four years. Tonkov led in Zülle only 13 seconds later. Pantani wasn’t in pink but he did get the green Climber’s Jersey. Before the 40-kilometer individual time trial in Trieste, the General Classification stood thus:

1. Alex Zülle

2. Marco Pantani @ 22 seconds

3. Pavel Tonkov @ 40 seconds

4. Giuseppe Guerini @ 57 seconds

5. Andrea Noè @ 1 minute 5 seconds

Zülle answered a question that cyclists debated in the early 1970s. Do you push big gears or spin little gears? Zülle’s time trial gave the answer. Spin big gears. On the long slightly downhill section followed by a flat road, he churned a gigantic 56 x 11, setting what was then a Giro time trial record of 53.77 kilometers per hour. At the halfway point he surged past Pantani, his 2-minute man. Zülle had now increased his lead to 2 minutes 2 seconds over Tonkov and Pantani was now in third at 3 minutes 48 seconds.

Stage seventeen, 215 kilometers going from Asiago to Selva Val Gardena, was il tappone. The riders had to cross the Duran, Staulanza, Marmolada and Sella (1998’s Cima Coppi), all crammed into the final 100 kilometers. The contenders had taken it easy in stage sixteen, their legs sore from the time trial. Now there could be no relaxation, all knew that a hungry Pantani would be seeking the lead on these difficult passes in the high Dolomites.

The classification riders made it to the Marmolada together. It was Tonkov who threw down the gauntlet on the long and relentless ascent and it was Pantani who accepted the challenge. Guerini made it up to the duo but under this terrible pressure, Zülle folded.

Tonkov had brought a knife to a gunfight and had to let the pair go. Now it was just Pantani smoothly climbing in the saddle with Guerini stuck to his rear wheel. Bartoli, who had raced as if each stage were the last, was paying the price for his earlier efforts and was near the back of the peloton.

Pantani and Guerini went over the top of the Marmolada with Tonkov about a minute back. From then on Guerini and Pantani worked together, scorching the descent, and in the valley before the Passo Sella they picked up a few earlier breakaways. On the final climb, the pickups were dropped and the two riders continued to increase their advantage with every pedal stroke. Guerini was allowed the stage win and Pantani was the maglia rosa. Underlining his complete collapse, Bartoli failed to make the time cutoff and was eliminated.

The new General Classification:

1. Marco Pantani

2. Pavel Tonkov @ 30 seconds

3. Giuseppe Guerini @ 31 seconds

4. Alex Zülle @ 1 minute 1 second

Marco Pantani leads Giuseppe Guerini in stage 17.

There were still two more challenging mountain stages remaining as well as a 34-kilometer time trial on the penultimate stage. Could Pantani accrue a large enough lead to withstand another race against the clock?

Stage eighteen had three major rated climbs that were stacked up in the final 45 kilometers, including a hilltop finish at Alpe di Pampeago. This certainly played to the Pirate’s advantage. There were seven of the best left on the final climb. Pantani slowly, without any noticeable jump, upped the pace. Tonkov held on, but behind him the string broke. The two were gone and as the gradient went from fourteen percent to over twenty, Pantani was not looking nearly as formidable as he had earlier. Tonkov, sensing the weakness, led over the final kilometer and won the sprint. Zülle lost almost a minute, making his job of reclaiming the race in the time trial more difficult. Pantani still led Tonkov by 27 seconds and Zülle was still in fourth, but 2 minutes 8 seconds back.

The final mountain stage had two major ascents before a hilltop finish, this time at Plan di Montecampione. It was one mountain stage too many for Zülle, who suffered a défaillance. At the top of the Cadino, the penultimate climb, he was almost eight minutes behind the leaders.

If anyone thought Pantani was running out of gas in this third week, he had an answer. As his gregario Podenzana was killing himself keeping the speed high (successfully: most of the peloton was well back down the road) Pantani erupted out from behind his wheel with an astonishing acceleration. Just as astonishing, Tonkov was on him like stink on poo. With the time trial looming, Pantani needed more time and Tonkov was in no mood to give it to him.

With about fifteen kilometers to go, Pantani slowed a bit and asked Tonkov to pull through. “Nothing doing”, seemed to be the reply. Further up the hill Pantani again motioned Tonkov to come through and this time he did. The two riders seemed to be almost perfectly matched. As the final three kilometers stiffened to over ten percent Pantani tried to get away again, his last chance to win the Giro. He’d already tossed aside his sunglasses and bandanna, now he removed the diamond stud from his nose, threw it away, and then rising out of the saddle, he lashed his bike with another brutal acceleration and this time Tonkov couldn’t take it. Slowly the gap grew and Pantani, hands on the drops and out of the saddle, gave it full gas. The gradient increased to 23 percent and Pantani kept up the pressure. Tonkov looked at last to have been broken. He had been forced to dig too deep one time too many. At the line Pantani had gained 57 seconds. Zülle lost a half-hour.

Marco Patani wins at Montecampione

Zülle’s soigneur Willy Voet thought the Swiss racer’s collapse was the needless result of incompetent doping. He wrote that Zülle had been brought along carefully with growth hormone and then a treatment of corticosteroids, and I assume also EPO, which his Festina team had become adept at using. Although Zülle was in superb condition for the start of the Giro, he saw how teammate Laurent Dufaux had overpowered the competition in the Tour of Romandie and asked for the same heavy dose of cortisone Dufaux had received. Voet was against it, thinking he had his Formula One engine perfectly tuned. So, according to Voet, Zülle turned to another soigneur on the team who injected him with “massive doses of corticosteroids”. Voet said that the “cortico” devoured the muscle that had been so carefully built up and after about ten days of racing in which Zülle was the strongest rider in the Giro peloton, he started falling apart.

The new General Classification:

1. Marco Pantani

2. Pavel Tonkov @ 1 minute 28 seconds

3. Giuseppe Guerini @ 5 minutes 11 seconds

With the final 34-kilometer time trial left, it was a race between Tonkov and Pantani. In the stage fifteen time trial Tonkov, a fine time trialist, had beaten Pantani by 2 minutes 4 seconds, or about three seconds per kilometer. Those three seconds per kilometer were roughly the amount of time Tonkov would need to take from Pantani this day in order to be the Giro winner. On paper the race was a dead heat.

Before the race started it was announced that two riders had hematocrits over 50 percent: Nicola Miceli, who had been sitting in fifth and Pantani teammate Riccardo Forconi.

Tonkov’s start was nearly perfect. If his stiff climbing style made one wince, his time trialing was perfection. Two minutes later Pantani roared out of the start house looking all aggression and taking crazy chances on the corners. The first time check was a shock. Pantani was ahead by two seconds.

The result was a stunner. Time trial specialist Serguei Gontchar won, but Pantani was third, only 30 seconds behind. Tonkov was fifth, 5 seconds slower than the remarkable Pirate.

Stage 21 time trial: Pantani is still first

Pantani had been getting stronger with every passing day and now was capable of taking on the big power men on their own turf. Pantani won the Giro by relentlessly applying pressure at every opportunity. It was a performance that can only be described as incredible, it being rare that a small man can summon up the absolute horsepower needed to drive his bike through the wind as fast as the bigger powerhouses.

Italy was insane with joy over a man they loved for his courage in adversity and his swashbuckling, fearless racing style. There was no Binda-Guerra, Coppi-Bartali or Moser-Saronni duel to divide Italy’s loyalty, Pantani had the passionate love of the tifosi all to himself. This was a long-delayed fulfillment of the promise Pantani had shown when he won the Girobio in 1992.

1998 Giro d'Italia final podium: from left, Tonkov, Patani and Guerini

Final 1998 Giro d’Italia General Classification:

1. Marco Pantani (Mercatone Uno-Bianchi): 98 hours 48 minutes 32 seconds

2. Pavel Tonkov (Mapei-Bricobi) @ 1 minute 33 seconds

3. Giuseppe Guerini (Polti) @ 6 minutes 51 seconds

4. Oskar Camenzind (Mapei-Bricobi) @ 12 minutes 16 seconds

5. Daniel Clavero (Vitalicio Seguros) @ 18 minutes 4 seconds

Climbers’ Competition:

1. Marco Pantani (Mercatone Uno-Bianchi): 89 points

2. José Jaime González (Kelme-Costa Blanca): 62

3. Pavel Tonkov (Mapei-Bricobi): 49

Points Competition:

1. Mariano Piccoli (Brescialat-Liquigas): 194 points

2. Marco Pantani (Mercatone Uno-Bianchi): 158

3. Gian Matteo Fagnini (Saeco-Cannondale): 156

* * *

As soon as the Giro was over, Pantani started to talk of riding the Tour de France. The events of the 1998 Tour traumatized professional cycling for years. The story was told in detail in the second volume of our The Story of the Tour de France, but a summary is necessary to understand many of the events in later Giri.

Doping was and is a part of the sport and while one may not be able to dope a donkey into being a thoroughbred, with modern drugs you can make a damn fast donkey. As we proceed through the sordid story of the 1998 Tour and later the 2001 Giro, the actions of the riders to protect themselves and their doping speak volumes.

On his way to the start of the 1998 Tour in Dublin, Ireland, Festina (Zülle’s team) soigneur Willy Voet was stopped by customs agents as he crossed from Belgium into France. Among the items found in Voet’s car were 234 doses of EPO, testosterone, amphetamines and other drugs that could have only one purpose, to illegally improve the performance of the riders on the Festina team. Bruno Roussel, the team director, expressed his astonishment at the facts surrounding Voet’s arrest.

Later, the police raided the Festina team warehouse and found still more drugs, including bottles labeled with specific riders’ names. Roussel said he was mystified by these findings and promised to hire a lawyer to deal with all of the defamatory things that had been written and said about the team.

Still in police custody, Voet began to sing, claiming that he had been acting on instructions from the Festina team management. Roussel said he was “shocked” at these statements.

Roussel and Festina team doctor Eric Rijckaert were taken into custody. While all of this was going on, the Tour de France was entering its sixth stage and Tour boss Jean-Marie Leblanc said that so far, the actions of the Festina team had not constituted an infraction of Tour rules and the occurrences outside of the Tour were not the Tour’s concern.

On July 15, one of the most important events in the fight against drugs in sport occurred. Roussel admitted that the Festina team had systematized its doping. His excuse was that since the riders were doping themselves, often with terribly dangerous substances like perfluorocarbon (Swiss rider Mauro Gianetti had nearly died during the 1998 Tour of Romandie after allegedly using the synthetic hemoglobin), it was safer to have the doping performed under the supervision of the team’s staff. That was too much and the team was booted from the Tour.

Yet, almost as a metaphor of how the pros handled irrefutable facts regarding their doping, Festina team members Richard Virenque and Laurent Brochard called a news conference to assert their innocence and vowed to continue riding in the Tour. A day later they relented and the team, including Zülle, withdrew from the Tour.

The Tour’s next act showed how completely everyone was willing to look the other way when they passed the train wreck of the Festina mess. Fifty-five riders were subjected to blood tests and none was found to have illegal substances in his system. The Tour then declared that this meant that the problem was confined to a few bad apples. What it really meant was that for decades the riders and their doctors had learned to dope so that drugs didn’t show up in the tests. And, in 1998 there was no test for EPO or human growth hormone. The team doctors protested that the Festina affair was bringing disrepute upon other teams and their professions. The fans hated to see their beloved riders singled out and thought that Festina was getting unfair treatment.

Back in March, a car belonging to the TVM team had been found to contain a large supply of drugs. That case was reopened. A few days later Roussel accepted responsibility for the systematic doping within the Festina team.

On July 24, the day of Tour stage twelve, more Festina riders and staff were arrested and the first TVM arrest occurred.

So how did the riders handle this? They became indignant. They were furious that the Festina riders had, like any other arrestees, been forced to strip in a French jail and were fuming that so much attention was focused on the ever-widening doping scandal instead of the race. On July 29, stage seventeen, the riders staged a strike. They started the stage slowly and sat down by their bikes at the site of the first intermediate sprint, Pantani being one of the strike’s leaders. After some talk with officials, they rode slowly to the finish with several TVM riders at the front holding hands, making the solidarity of the peloton clear.

There were more arrests. Several teams, including all four Spanish squads, were feeling the heat and quit the Tour. It was thought that the Festina scandal might just ruin the Tour. It didn’t. It didn’t ruin the Tour because Marco Pantani electrified the world with a fabulous performance that took a lot of the attention away from the doping scandal.

.