1997 Giro d'Italia

80th edition: May 17- June 8

Results, stages with running GC, map, photos and history

1996 Giro | 1998 Giro | Giro d'Italia Database | Race Profile | 1997 Giro Quick Facts | 1997 Giro d'Italia Final GC | Stage results with running GC | The Story of the 1997 Giro d'Italia

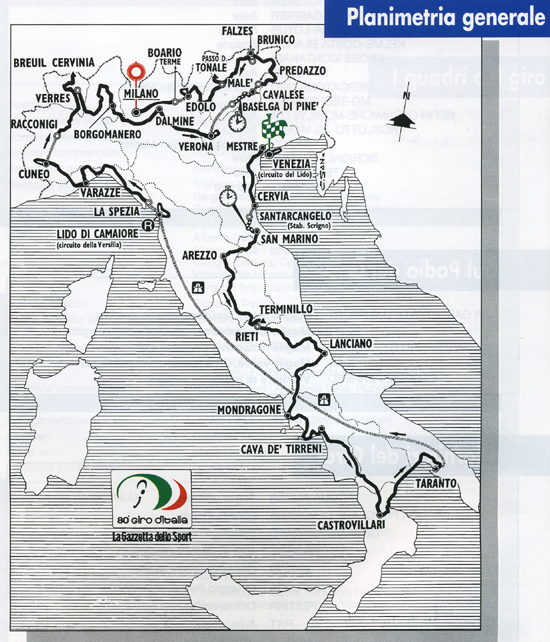

Map of the 1997 Giro d'Italia

3,918 kilometers race at an average speed of 38.08 km/hr

180 starters and 110 classified finishers

The 1997 Giro was particularly hilly.

1996 Giro champion Pavel Tonkov took the lead and focused most of his attention on Luc Leblanc.

When the race hit the high mountains, while Tonkov was watching Leblanc, Ivan Gotti rode off and to take the lead, which he was able to keep to the end.

Italian hope Marco Pantani crashed out of the Giro but recovered in time to get third in the Tour de France.

Les Woodland's book Cycling Heroes: The Golden Years is available as an audiobook here.

1997 Giro d'Italia Complete Final General Classification:

Ivan Gotti (Saeco) 102hr 53min 58sec

Ivan Gotti (Saeco) 102hr 53min 58sec- Pavel Tonkov (Mapei-GB) @ 1min 27sec

- Giuseppe Guerini (Polti) @ 7min 40sec

- Nicola Miceli (AKI-Safi) @ 12min 20sec

- Serguei Gonchar (AKI-Safi) @ 12min 44sec

- Wladimir Belli (Brescialat) @ 12min 48sec

- Giuseppe Di Grande (Mapei-GB) @ 12min 54sec

- Marcos Antonio Serrano (Kelme-Costa Blanca) @ 16min 7sec

- Stefano Garzelli (Mercatone Uno) @ 18min 8sec

- José Luis Rubiera (Kelme-Costa Blanca) @ 18min 56sec

- Andrea Noè (Ascics) @ 20min 51sec

- Felix Manuel Garcia Casas (Festina) @ 21min 50sec

- Paolo Salvoldelli (Roslotto-ZG Mobili) @ 24min 20sec

- Dario Frigo (Saeco) @ 31min 35sec

- José Jaime Gonzalez (Kelme-Costa Blanca) @ 37min 34sec

- Alberto Volpi (Batik-Del Monte) @ 41min 32sec

- Massimo Podenzana (Mercatone Uno) @ 43min 28sec

- Roberto Conti (Mercatone Uno) @ 47min 22sec

- Axel Merckx (Polti) @ 47min 44sec

- Evgeni Berzin (Batik-Del Monte) @ 49min 2sec

- Riccardo Forconi (Amore & Vita-Forzacore) @ 51min 47sec

- José Javier Gomez (Kelme-Costa Blanca) @ 53min 47sec

- Massimiliano Gentili (Cantina Tollo) @ 54min 16sec

- Roberto Petito (Saeco) @ 1hr 2min 58sec

- Paolo Bettini (MG-Technogym) @ 1hr 4min 55sec

- Marcello Siboni (Mercatone Uno) @ 1hr 5min 6sec

- Felice Puttini (Refin-Mobilvetta) @ 1hr 13min 14sec

- Gianni Faresin (Mapei-GB) @ 1hr 14min 37sec

- Daniele De Paoli (Ros Mary-Minotti) @ 1hr 15min 11sec

- Marco Velo (Brescialat) @ 1hr 16min 10sec

- Fabian Jeker (Festina) @ 1hr 16min 18sec

- Roberto Sgambelluri (Brescialat) @ 1hr 29min 16sec

- Michele Coppolillo (MG-Technogym) @ 1hr 30min 1sec

- Gianluca Bortolami (Festina) @ 1hr 30min 32sec

- Leonardo Calzavara (AKI-Safi) @ 1hr 33min 24sec

- Germano Pierdomenico (Cantina-Tollo) @ 1hr 34min 22sec

- Dimitri Konyshev (Roslotto-ZG Mobili) @ 1hr 36min 55sec

- Massimo Donati (Saeco) @ 1hr 37min 32sec

- Oscar Pellicioli (Mercatone Uno) @ 1hr 39min 50sec

- Bruno Cenghialta (Batik-Del Monte) @ 1hr 42min 29sec

- Luca Mazzanti (Refin-Mobilvetta) @ 1hr 43min 22sec

- Andrea Paluan (Cantina Tollo) @ 1hr 43min 56sec

- Sergio Barbero (Mercatone Uno) @ 1hr 45min 13sec

- Nicola Loda (MG-Technogym) @ 1hr 46min 24sec

- Pavel Padrnos (Roslotto-ZG Mobili) @ 1hr 46min 28sec

- Marco Fincato (Roslotto-ZG Mobili) @ 1hr 47min 56sec

- Alexei Sivikov (Roslotto-ZG Mobili) @ 1hr 49min 21sec

- Mariano Piccoli (Brescialat) @ 1hr 53min 17sec

- Andrea Patuelli (Amore & Vita-Forzacore) @ 1hr 59min 49sec

- Alvaro Lozano (Kross-Montanari) @ 2hr 0min 22sec

- Serguei Ouslamine (Refin-Mobilvetta) @ 2hr 3min 27sec

- Arsenio Gonzalez (Kelme-Costa Blanca) @ 2hr 6min 29sec

- Gabriele Missaglia (Mapei-GB) @ 2hr 6min 34sec

- Fausto Dotti (Ros Mary-Minotti) @ 2hr 9min16sec

- Marco Vergnani (Amore & Vita-Forzacore) @ 2hr 11min 54sec

- Angelo Lecchi (MG-Technogym) @ 2hr 14min 40sec

- Maurizio Molinari (Asics) @ 2hr 14min 46sec

- Stefano Finesso (Ros Mary-Minotti) @ 2hr 16min 15sec

- Martin Hvastija (Cantina Tollo) @ 2hr 19min 17sec

- Marco Della Vedova (Brescialat) @ 2hr 21min 16sec

- Michele Poser (Ros Mary-Minotti) @ 2hr 25min 53sec

- Mirko Gualdi (Polti) @ 2hr 26min 21sec

- Fabio Roscioli (Asics) @ 2hr 29min 7sec

- Jaime Javier Hernandez (Festina) @ 2hr 29min 50sec

- Michele Laddomada (Amore & Vita-Forzacore) @ 2hr 31min 36sec

- Bruno Boscardin (Festina) @ 2hr 33min 52sec

- Giampaolo Mondini (Amore & Vita-Forzacore) @ 2hr 39min 18sec

- Lylian Lebreton (Festina) @ 2hr 40min 53sec

- Valerio Tebaldi (Festina) @ 2hr 43min 17sec

- Alessandro Baronti (Asics) @ 2hr 44min 16sec

- Francesco Frattini (Batik-Del Monte) @ 2hr 44min 35sec

- Alexandre Moos (Saeco) @ 2hr 48min 5sec

- Omar Pumar (Brescialat) @ 2hr 48min 42sec

- Alessandro Pozzi (Cantina Tollo) @ 2hr 49min 38sec

- Gianni Bugno (Mapei-GB) @ 2hr 50min 7sec

- Roberto Caruso (Ros Mary-Minotti) @ 2hr 53min 59sec

- Denis Zanette (AKI-Safi) @ 2hr 54min 29sec

- José Angel Vidal (Kelme-Costa Blanca) @ 2hr 54min 41sec

- Mirco Crepaldi (Polti) @ 2hr 55min 14sec

- Viatcheslav Djavanian (Roslotto-ZG Mobili) @ 2hr 55min 26sec

- Francisco Cabello (Kelme-Costa Blanca) @ 2hr 55min 31sec

- Mario Chiesa (Asics) @ 2hr 55min 58sec

- Massimo Apollonio (Scrigno-Gaerne) @ 2hr 59min 24sec

- David Tani (Ros Mary-Minotti) @ 2hr 59min 26sec

- Glenn Magnusson (Amore & Vita-Forzacore) @ 2hr 59min 36sec

- Cristiano Frattini (Brescialat) @ 3hr 1min 13sec

- Torsten Schmidt (Roslotto-ZG Mobili) @ 3hr 1min 30sec

- Mauro Bettin (Refin-Mobilvetta) @ 3hr 3min 39sec

- Mario Cipollini (Saeco) @ 3hr 5min 38sec

- Oscar Dalla Costa (AKI-Safi) @ 3hr 9min 47sec

- Rossano Brasi (Polti) @ 3hr 13min 54sec

- Fabiano Fontanelli (MG-Technogym) @ 3hr 14min 24sec

- Paolo Alberati (Scrigno-Gaerne) @ 3hr 15min 34sec

- Serguei Outschakov (Polti) @ 3hr 16min 16sec

- Stefano Giraldi (Kross-Montanari) @ 3hr 17min 14sec

- Davide Bramati (Mapei-GB) @ 3hr 17min 59sec

- Sauro Gallorini (Scrigno-Gaerne) @ 3hr 21min 7sec

- Paolo Fornaciari (Saeco) @ 3hr 24min 44sec

- Dario Bottaro (Mercatone Uno) @ 3hr 25min 6sec

- Zbigniew Spruch (Mapei-GB) @ 3hr 26min 9sec

- Gianluca Pianegonda (Mapei-GB) @ 3hr 26min 43sec

- Fabrizio Bontempi (Brescialat) @ 3hr 24min 24sec

- Giuseppe Calcaterra (Saeco) @ 3hr 34min 49sec

- Uwe Peschel (Cantina Tollo) @ 3hr 36min 24sec

- Marcel Wüst (Festina) @ 3hr 37min 48sec

- Enrico Cassani (Polti) @ 3hr 40min 47sec

- Mauro-Antonio Sanbaromita (MG-Technogym) @ 3hr 51min 36sec

- Sandro Giacomelli (Amore & Vita-Forzacore) @ 4hr 4min 38sec

- Michelangelo Cauz (AKI-Safi) @ 4hr 5min 44sec

- Marco-Antonio Di Renzo (Cantina Tollo) @ 4hr 22min23sec

Points Classification:

Mario Cipollini (Saeco): 202 points

Mario Cipollini (Saeco): 202 points- Dimitri Konyshev (Mapei-GB): 146

- Glenn Magnusson (Amore & Vita-Forzacore): 145

- Pavel Tonkov (Mapei-GB): 121

- Ivan Gotti (Saeco): 102

Climbers' Classification:

José Jaime González (Kelme-Costa Blanca): 99 points

José Jaime González (Kelme-Costa Blanca): 99 points- Mariano Piccoli (Brescialat): 35

- Stefano Garzelli (Mercatone Uno): 28

- Pavel Tonkov (Mapei-GB): 24

- Ivan Gotti (Saeco): 23

Intergiro:

Dimitri Konyshev (Roslotto-ZG Mobili): 52hr 48min 18sec

Dimitri Konyshev (Roslotto-ZG Mobili): 52hr 48min 18sec- Mario Cipollini (Saeco) @ 3min 1sec

- Glenn Magnusson (Amore & Vita-Forzacore) @ 3min 15sec

- Serguei Gonthcar (AKI-Safi) @ 3min 22sec

- Evgeni Berzin (Batik-Del Monte) @ 3min 41sec

Team Classification (time):

- Kelme-Costa Blanca: 309hr 26min 9sec

- Mapei-GB @ 14min 7sec

- Saeco @ 33min 18sec

- Mercatone Uno @ 36min 21sec

- AKI-Safi @ 40min 12sec

Team Classification (points):

- Saeco: 399 points

- Mapei-GB: 391

- Polti: 367

- Roslotto-ZG Mobili: 365

- AKI-Safi: 306

1997 Giro stage results with running GC:

Saturday, May 17: Stage 1, Venezia - Venezia (Lido circuit), 128 km

- Mario Cipollini: 2hr 38min 17sec

- Nicola Minali s.t.

- Endrio Leoni s.t.

- Filippo Meloni s.t.

- Mirko Rossato s.t.

- Marcel Wüst s.t.

- Gabriele Balducci s.t.

- Angel Edo s.t.

- Gabriele Missaglia s.t.

- Serguei Outschakov s.t.

GC after Stage 1:

- Mario Cipollini: 2hr 38min 5sec

- Nicola Minali @ 4sec

- Endrio Leoni @ 8sec

Sunday, May 18: Stage 2, Mestre - Cervia, 211 km

- Mario Cipollini: 5hr 9min 47sec

- Jan Svorada s.t.

- Endrio Leoni s.t.

- Maurizio Tomi s.t.

- Gabriele Balducci s.t.

- Massimo Apollonio s.t.

- Gabriele Missaglia s.t.

- Glen Magnusson s.t.

- Mariano Piccoli s.t.

- Evgeni Berzin s.t.

GC after Stage 2:

- Mario Cipollini:7hr 47min 40sec

- Endrio Leoni @ 16sec

- Jan Svorada s.t.

Monday, May 19: Stage 3, Santarcangelo di Romagna (Scrigno headquarters) - San Marino 18 km individual time trial (cronometro)

![]() Major ascent: San Marino

Major ascent: San Marino

- Pavel Tonkov: 31min 42sec

- Evgeni Berzin @ 21sec

- Roberti Petito @ 32sec

- Luc Leblanc @ 37sec

- Piotr Ugrumov @ 53sec

- Ivan Gotti @ 55sec

- Gabriele Colombo @ 1min 2sec

- Andrea Noè @ 1min 13sec

- Giuseppe Guerini @ 1min 16sec

- Juan Carlos Dominguez @ 1min 22sec

- Marco Pantani @ 1min 23sec

- Nicola Miceli @ 1min 24sec

- Paolo Savoldelli @ 1min 35sec

- Enrico Zaina @ 1min 36sec

- Michele Coppolillo @ 1min 41sec

- Wladimir Belli @ 1min 43sec

- Gianni Faresin @ 1min 47sec

- Serguei Gontchar @ 1min 48sec

- Giuseppe Di Grande @ 2min 0sec

- Vlaldislav Bobrik s.t.

GC after Stage 3:

- Pavel Tonkov: 8hr 20min 5sec

- Evgen Berzin @ 1sec

- Roberto Petito @ 12sec

- Luc Leblanc @ 37sec

- Gabriele Colombo @ 42sec

- Piotr Ugrumov @ 53sec

- Ivan Gotti @ 55sec

- Andrea Noé @ 1min 13sec

- Enrico Zaina @ 1min 16sec

- Giuseppe Guerini s.t.

Tuesday, May 20: Stage 4, San Marino - Arezzo, 156 km

![]() Major ascents: Urbino, Valico di Bocca Seriola

Major ascents: Urbino, Valico di Bocca Seriola

- Mario Cipollini: 3hr 57min 58sec. 39.33 km/hr

- Endrio Leoni s.t.

- Angel Edo s.t.

- Glenn Magnusson s.t.

- Fabio Baldato s.t.

- Mirko Rossato s.t.

- Gabriele Missaglia s.t.

- Mario Traversoni s.t.

- Marcel Wüst s.t.

- Mariano Piccoli s.t.

GC after stage 4:

- Pavel Tonkov: 12hr 18min 3sec

- Evgeni Berzin @ 1sec

- Roberto Petito @ 12sec

- Luc Leblanc @ 37sec

- Piotr Ugrumov @ 53sec

- Ivan Gotti @ 55sec

- Andrea Noé @ 1min 13sec

- Enrico Zaina @ 1min 16sec

- Giuseppe Guerini s.t.

- Juan Carlos Dominguez @ 1min 22sec

- Marco Pantani @ 1min 23sec

- Nicola Miceli @ 1min 24sec

Wednesday, May 21: Stage 5, Arezzo - Terminillo, 215 km

![]() Major ascents: Greccio, Terminillo

Major ascents: Greccio, Terminillo

- Pavel Tonkov: 6hr 14min 58sec

- Luc Leblanc s.t.

- Marco Pantani s.t.

- Ivan Gotti s.t.

- Michele Coppolillo @ 2sec

- Leonardo Piepoli @ 18sec

- Andrea Noè s.t.

- Aleksandr Shefer @ 29sec

- Gilberto Simoni @ 47sec

- Roberto Petito @ 49sec

GC after Stage 5:

- Pavel Tonkov: 18hr 32min 49sec

- Luc Leblanc @ 41sec

- Ivan Gotti @ 1min 7sec

- Roberto Petito @ 1min 13sec(?)

- Marco Pantani @ 1min 31sec

- Andrea Noè @ 1min 43sec

- Michele Coppolillo @ 2min 9sec

- Paolo Savoldelli @ 2min 40sec

- Leonardo Piepoli @ 2min 49sec

- Aleksandr Shefer @ 3min 5sec

Thursday, May 22: Stage 6, Rieti - Lanciano, 210 km

![]() Major ascents: Valico Sella di Corno, Valico di Trincee, Chieti

Major ascents: Valico Sella di Corno, Valico di Trincee, Chieti

- Roberto Sgambelluri: 5hr 9min 57sec

- Dario Frigo s.t.

- Michele Coppolillo s.t.

- Tobias Steinhauser s.t.

- Fabi Baldato @ 16sec

- Marcel Wüst s.t.

- Dimitri Konyshev s.t.

- Wladimir Belli s.t.

- Roberto Moretti s.t.

- Massimiliano Gentili s.t.

GC after Stage 6:

- Pavel Tonkov: 23hr 43min 2sec

- Luc Leblanc @ 41sec

- Ivan Gotti @ 1min 7sec

- Roberto Petito @ 1min 13sec

- Marco Pantani @ 1min 31sec

- Andrea Noé @ 1min 43sec

- Michele Coppolillo @ 1min 49sec

- Paolo Savoldelli @ 2min 40sec

- Leonardo Piepoli @ 2min 49sec

- Aleksandr Shefer @ 3min 5sec

Friday, May 23: Stage 7, Lanciano - Mondragone, 210 km

![]() Major ascents: Valico della Forchetta Palena, Svincolo Rionero Sannitico

Major ascents: Valico della Forchetta Palena, Svincolo Rionero Sannitico

- Marcel Wüst: 5hr 15min 40sec

- Mirko Rossato s.t.

- Endrio Leoni s.t.

- Glenn Magnusson s.t.

- Mario Traversoni s.t.

- Mario Manzoni s.t.

- Daniele Contrini s.t.

- Gabriele Balducci s.t.

- Jürgen Werner s.t.

- Fabio Baldato s.t.

GC after Stage 7:

- Pavel Tonkov: 28hr 58min 42sec

- Luc Leblenc @ 41sec

- Ivan Gotti @ 1min 7sec

- Roberto Petito @ 1min 13sec

- Marco Pantani @ 1min 31sec

- Andrea Noè @ 1min 43sec

- Michele Coppolillo @ 1min 49sec

- Paolo Savoldelli @ 2min 40sec

- Leonardo Piepoli @ 2min 49sec

- Aleksandr Shefer @ 3min 5sec

Saturday, May 24: Stage 8, Mondragone - Cava de' Tirreni, 212 km

Marco Pantani crashed on the descent of the Valico di Chiunzi and abandoned

![]() Major ascents: Moiano, Colle di Fontanelle, Valico di Chiunzi

Major ascents: Moiano, Colle di Fontanelle, Valico di Chiunzi

- Mario Manzoni: 5hr 20min 9sec

- Stefano Giraldi @ 23sec

- Maurizio Molinari @ 25sec

- Giampaolo Mondini s.t.

- Mariano Piccoli @ 35sec

- Denis Zanette s.t.

- Nicola Loda s.t.

- Andrea Vatteroni s.t.

- Andrea Paluan s.t.

- Andrea Brognara s.t.

GC after Stage 8:

- Pavel Tonkov: 34hr 32min 52sec

- Luc Leblanc @ 41sec

- Ivan Gotti @ 1min 7sec

- Roberto Petito @ 1min 13sec

- Andrea Paluan @ 1min 39sec

- Andrea Noè @ 1min 43sec

- Michele Coppolillo @ 1min 49sec

- Paolo Savoldelli @ 2min 40sec

- Leonardo Piepoli @ 2min 49sec

- Aleksandr Shefer @ 3min 5sec

Sunday, May 25: Stage 9, Cava de' Tirreni - Castrovillari, 232 km

![]() Major ascents: Scorzo, Casalbuono, Valico di Fortino, Valico di Cerri, Pian della Menta, Valico di Campo Tenese

Major ascents: Scorzo, Casalbuono, Valico di Fortino, Valico di Cerri, Pian della Menta, Valico di Campo Tenese

- Dimitri Konyshev: 6hr 14min 18sec

- Mariano Piccoli s.t.

- Roberto Petito s.t.

- Massimiliano Gentili s.t.

- Marco Vergnani s.t.

- Paolo Savoldelli s.t.

- Martin Hvastija s.t.

- Nicola Loda s.t.

- Alessio Barbagli s.t.

- Paolo Lanfranchi s.t.

GC after Stage 9:

- Pavel Tonkov: 40hr 47min 10sec

- Luc Leblanc @ 41sec

- Ivan Gotti @ 1min 7sec

- Roberto Petito @ 1min 9sec

- Andrea Paluan @ 1min 39sec

- Andrea Noè @ 1min 43sec

- Michele Coppolillo @ 1min 49sec

- Paolo Savoldelli @ 2min 40sec

- Leonardo Piepoli @ 2min 49sec

- Aleksander Shefer @ 3min 5sec

Monday, May 26: Stage 10, Castrovillari - Taranto, 195 km

- Mario Cipollini: 5hr 10min 6sec

- Endrio Leoni s.t.

- Fabio Baldato s.t.

- Marcel Wüst s.t.

- Mario Traversoni s.t.

- Mario Manzoni s.t.

- Gabriele Missaglia s.t.

- Enrico Cassani s.t.

- Glenn Magnusson s.t.

- Angel Edo s.t.

GC after Stage 10:

- Pavel Tonkov: 45hr 57min 16sec

- Luc Leblanc @ 41sec

- Ivan Gotti @ 1min 7sec

- Roberto Petito @ 1min 9sec

- Andrea Paluan @ 1min 39sec

- Andrea Noè @ 1min 43sec

- Michele Coppolillo @ 1min 49sec

- Paolo Savoldelli @ 2min 40sec

- Leonardo Piepoli @ 2min 49sec

- Aleksandre Shefer @ 3min 5sec

Tuesday, May 27: Rest day (giorno di riposo)

Wendesday, May 28: Stage 11, Lido di Camaiore (circuito della Versilia), 155 km

![]() Major ascents: Colli di Pedrona x 3

Major ascents: Colli di Pedrona x 3

- Gabriele Missaglia: 3hr 36min 24sec

- Andrea Vatteroni s.t.

- Mirko Celestino s.t.

- Massimo Podenzana s.t.

- Francisco Cabello @ 15sec

- Marco Fincato s.t.

- Daniele De Paoli s.t.

- Cristiano Frattini s.t.

- Mario Cipollini s.t.

- Alessandro Spezialetti s.t.

GC after Stage 11:

- Pavel Tonkov: 49hr 34min 40sec

- Luc Leblanc @ 41sec

- Ivan Gotti @ 1min 7sec

- Roberto Petito @ 1min 9sec

- Andrea Paluan @ 1min 39sec

- Andrea Noè @ 1min 43sec

- Paolo Savoldelli @ 2min 40sec

- Leonardo Piepoli @ 2min 49sec

- Aleksandr Shefer @ 3min 5sec

- Gilberto Simoni @ 3min 14sec

Thursday, May 29: Stage 12, La Spezia - Varazze, 214 km

![]() Major ascents: Passo del Bracco, Campi, Passo del Faiallo, Monte Beigua

Major ascents: Passo del Bracco, Campi, Passo del Faiallo, Monte Beigua

- Giuseppe Di Grande: 5hr 47min 14sec

- Marcos Antonio Serrano s.t.

- Aleksandr Shefer s.t.

- Axel Merckx s.t.

- Leonardo Piepoli s.t.

- Wladimir Belli @ 12sec

- Giuseppe Guerini s.t.

- Luc Leblanc s.t.

- Ivan Gotti s.t.

- Pavel Tonkov s.t.

GC after Stage 12:

- Pavel Tonkov: 55hr 22min 6sec

- Luc Leblanc @ 41sec

- Ivan Gotti @ 1min 7sec

- Andrea Noè @ 1min 49sec

- Leonardo Piepoli @ 2min 37sec

- Aleksandr Shefer @ 2min 49sec

- Paolo Savoldelli @ 2min 51sec

- Giuseppe Di Grande @ 3min 38sec

Friday, May 30: Stage 13, Varazze - Cuneo, 150 km

![]() Major ascent: Tetti di Montezemola

Major ascent: Tetti di Montezemola

- Glenn Magnusson: 3hr 25min 4sec

- Mirko Rossato @ 1sec

- Mario Cipollini s.t.

- Mario Traversoni s.t.

- Fabio Baldato s.t.

- Mariano Piccoli s.t.

- Nicola Loda s.t.

- Endrio Leoni s.t.

- Manuele Scopsi s.t.

- Enrico Cassani s.t.

GC after Stage 13:

- Pavel Tonkov: 58hr 47min 11sec

- Luc Leblanc @ 41sec

- Ivan Gotti @ 1min 7sec

- Andrea Noè @ 1min 49sec

- Leonardo Piepoli @ 2min 37sec

- Aleksandr Shefer @ 2min 49sec

- Paolo Savoldelli @ 2min 51sec

- Giuseppe Di Grande @ 2min 38sec

Saturday, May 31: Stage 14, Racconigi - Breuil Cervinia, 240 km

![]() Major ascents: Champremier, Col de Saint Pantaleon, Il Cristallo

Major ascents: Champremier, Col de Saint Pantaleon, Il Cristallo

- Ivan Gotti: 7hr 6min 32sec. 33.761 km/hr

- Nicola Miceli @ 39sec

- Stefano Garzelli @ 1min 20sec

- José Jaime Gonzalez @ 1min 46sec

- Pavel Tonkov s.t.

- Leonardo Piepoli s.t.

- Aleksandr Shefer s.t.

- Axel Merckx s.t.

- Daniele De Paoli @ 3min 12sec

- Giuseppe Guerini @ 3min 14sec

GC after Stage 14:

- Ivan Gotti: 65hr 54min 38sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 51sec

- Luc Leblanc @ 3min 2sec

- Leonardo Piepoli @ 3min 28sec

- Aleksandr Shefer @ 3min 40sec

- Nicola Miceli @ 3min 45sec

- Axel Merckx @ 5min 52sec

Sunday, June 1: Stage 15, Verrès - Borgomanero, 173 km

![]() Major ascent: Mattarone

Major ascent: Mattarone

- Alessandro Baronti: 4hr 59min 23sec. 38.532 km/hr

- Filippo Casagrande s.t.

- Paolo Savoldelli s.t.

- Riccardo Forconi @ 3sec

- Andrea Noè @ 50sec

- Paolo Bettini s.t.

- Giuseppe Di Grande s.t.

- Daniele De Paoli s.t.

- Wladimir Belli s.t.

- Luc Leblanc s.t.

GC after Stage 15:

- Ivan Gotti: 70hr 24min 51sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 51sec

- Luc Leblanc @ 3min 2sec

- Aleksandr Shefer @ 3min 40sec

- Nicola Miceli @ 3min 45sec

- Giuseppe Guerini @ 6min 17sec

- Giuseppe Di Grande @ 7min 56sec

- Wladimir Belli @ 8min 17sec

- Axel Merckx @ 9min 42sec

- Serguei Gontchar @ 10min 26sec

Monday, June 2: Stage 16, Borgomanero - Dalmine, 158 km

- Fabiano Fontanelli: 3hr 29min 5sec. 45.34 km/hr

- Fabio Roscioli s.t.

- Angelo Lecchi s.t.

- Alberto Volpi s.t.

- Glenn Magnusson s.t.

- Mirko Rossato s.t.

- Mario Cipollini s.t.

- Marcel Wüst s.t.

- Mario Traversoni s.t.

- Mario Manzoni s.t.

GC after Stage 16:

- Ivan Gotti: 73hr 53min 56sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 51sec

- Luc Leblanc @ 3min 2sec

- Aleksandr Shefer @ 3min 40sec

- Nicola Miceli @ 4min 7sec

- Giuseppe Guerini @ 6min 17sec

- Giuseppe Di Grande @ 7min 56sec

- WLladimir Belli @ 8min 17sec

- Axel Merckx @ 9min 42sec

- Serguei Gontchar @ 10min 26sec

Tuesday, June 3: Stage 17, Dalmina - Verona (circuito delle Torricelle), 200 km

![]() Ascents: Torricelle x 5

Ascents: Torricelle x 5

- Mirko Gualdi: 4hr 27min 41sec. 44.829 km/hr

- Alessandro Pozzi s.t.

- José Jaime Gonzalez s.t.

- Mariano Piccoli @ 31sec

- Marco Vergnani s.t.

- Cristian Gasperoni s.t.

- Andrea Brognara s.t.

- Gianni Faresin s.t.

- Stefano Finesso s.t.

- Viatcheslav Djavanian @ 1min 31sec

GC after Stage 17:

- Ivan Gotti: 78hr 27min 23sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 51sec

- Luc Leblanc @ 3min 2sec

- Aleksandr Shefer @ 3min 40sec

- Nicola Miceli @ 4min 7sec

- Giuseppe Guerini @ 6min 17sec

- Giuseppe Di Grande @ 7min 56sec

- Wladimir Belli @ 8min 17sec

- Axel Merckx @ 9min 42sec

- Serguei Gontchar @ 10min 26sec

Wednesday, June 4: Stage 18, Beselga di Pinè - Cavalese 40 km individual time trial (cronometro)

- Serguei Gontchar: 47min 18sec

- Evgeni Berzin @ 1min 8sec

- Bruno Boscardin @ 1min 31sec

- Pavel Padrnos @ 1min 54sec

- José Luis Rubiera @ 2min 6sec

- Denis Zanette @ 2min 27sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 2min 30sec

- Paolo Savoldelli @ 2min 33sec

- Giuseppe Guerini s.t.

- Germano Pierdomenico @ 2min 36sec

- Ivan Gotti @ 2min 44sec

- Michelangelo Cauz @ 2min 54sec

- Alexei Sivakov @ 2min 55sec

- Marco Fincato @ 3min 1sec

- Giuseppe Di Grande @ 3min 7sec

- Jaime Hernandez @ 3min 13sec

- Roberto Petito @ 3min 17sec

- Michele Poser s.t.

- Stefano Garzelli @ 3min 22sec

- Marco Velo @ 3min 23sec

GC after Stage 18

- Ivan Gotti: 79hr 17min 25sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 37sec

- Luc Leblanc @ 4min 6sec

- Aleksandr Shefer @ 5min 19sec

- Nicola Miceli @ 5min 48sec

- Giuseppe Guerini @ 6min 6sec

- Serguei Gontchar @ 7min 42sec

- Giuseppe Di Grande @ 8min 19sec

- Wladimir Belli @ 10min 30sec

- Axel Merckx @ 11min 14sec

Thursday, June 5: Stage 19, Predazzo - Falzes, 222 km

![]() Major ascents: Passo di Constalunga, Passo di Pinei, Passo di Sella, Passo Pordoi, Passo di Campolongo, Passo Furcia, Valico di Riomolino, Falzes

Major ascents: Passo di Constalunga, Passo di Pinei, Passo di Sella, Passo Pordoi, Passo di Campolongo, Passo Furcia, Valico di Riomolino, Falzes

- José Luis Rubiera: 7hr 0min 2sec

- Roberto Conti @ 3min 6sec

- Giuseppe Guerini s.t.

- Ivan Gotti @ 3min 8sec

- José Jaime Gonzalez s.t.

- Andrea Noé @ 3min 33sec

- Stefano Garzelli @ 4min 1sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 4min 3sec

- Roberto Petito s.t.

- Dario Frigo s.t.

- Marcos Serrano s.t.

- Wladimir Belli @ 5min 2sec

- Dimitri Konyshev @ 5min 39sec

- Nicola Miceli @ 5min 53sec

- Francesco Secchiari s.t.

- Paolo Savoldelli s.t.

- Serguei Gontchar s.t.

- Giuseppe Di Grande s.t.

- Alexandre Moos s.t.

- Torsten Schmidt @ 7min 18sec

GC after Stage 19:

- Ivan Gotti: 86hr 20min 35sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 1min 32sec

- Giuseppe Guerini @ 6min 0sec

- Nicla Miceli @ 8min 33sec

- Serguei Gontchar @ 10min 27sec

- Giuseppe Di Grande @ 11min 4sec

- Wladimir Belli @ 12min 44sec

- Marcos Serrano @ 14min 0sec

- Stefano Garzelli @ 14min 42sec

- José Luis Rubiera @ 15min 9sec

Friday, June 6: Stage 20, Brunico - Passo del Tonale (Val di Sole), 176 km

![]() Major ascents: Terento, Passo Mendola, Passo del Tonale

Major ascents: Terento, Passo Mendola, Passo del Tonale

- José Jaime Gonzalez: 4hr 53min 3sec

- Massimo Podenzana @ 1min 43sec

- Felice Puttini @ 2min 10sec

- Gabriele Missaglia @ 3min 2sec

- Fausto Dotti s.t.

- Germano Pierdomenico @ 4min 2sec

- Bruno Boscardin @ 4min 50sec

- Evgeni Berzin @ 5min 34sec

- Alessandro Baronti @ 7min 41sec

- Andrea Noè @ 10min 10sec

GC after Stage 20:

- Ivan Gotti: 91hr 15min 48sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 1min 32sec

- Giuseppe Guerini @ 6min 0sec

- Serguei Gontchar @ 10min 27sec

- Nicola Miceli @ 10min 40sec

- Giuseppe Di Grande @ 11min 4sec

- Wladimir Belli @ 12min 44sec

- Marcos Serrano @ 14min 0sec

- Stefano Garzelli @ 14min 42sec

- José Luis Rubiera @ 17min 16sec

Saturday, June 7: Stage 21, Malè (Val di Sole) - Edolo, 238 km

![]() Major Ascents: Campo Carlo Magno, Roncone, Goletto di Cadino, Aprica, Passo di Mortirolo

Major Ascents: Campo Carlo Magno, Roncone, Goletto di Cadino, Aprica, Passo di Mortirolo

- Pavel Tonkov: 7hr 13min 36sec

- Ivan Gotti @ 1sec

- Wladimir Belli s.t.

- José Luis Rubiera @ 1min 33sec

- Andrea Noè s.t.

- Nicola Miceli s.t.

- Giuseppe Guerini s.t.

- Giuseppe Di Grande s.t.

- Daniele De Paoli @ 2min 0sec

- Serguei Gontchar s.t.

- Marcos Serrano s.t.

- Felix Garcia s.t.

- Stefano Garzelli @ 3min 19sec

- Paolo Savoldelli @ 4min 44sec

- Marco Fincato s.t.

- Massimiliano Gentili s.t.

- Dario Frigo @ 4min 48sec

- Leonardo Calzavara @ 6min 25sec

- Marco Velo s.t.

- Marcello Siboni s.t.

GC after Stage 21:

- Ivan Gotti: 98hr 29min 17sec

- Pavel Tonkov @ 1min 27sec

- Giuseppe Guerini @ 7min 40sec

- Nicola Miceli @ 12min 20sec

- Serguei Gontchar @ 12min 44sec

- Wladimir Belli @ 12min 48sec

- Giuseppe Di Grande @ 12min 54sec

- Marcos Serrano @ 16min 7sec

- Stefano Garzelli @ 18min 8sec

- José Luis Rubiera @ 18min 56sec

Sunday, June 8: 22nd and Final Stage, Boario Terme - Milano, 165 km

- Mario Cipollini: 4hr 24min 41sec

- Glenn Magnusson s.t.

- Luca Mazzanti s.t.

- Nicola Loda s.t.

- Marcel Wüst s.t.

- Mariano Piccoli s.t.

- Denis Zanette s.t.

- Zbigniew Spruch s.t.

- Alexei Sivikov s.t.

- Martin Hvastija s.t.

The Story of the 1997 Giro d'Italia

This excerpt is from "The Story of the Giro d'Italia", Volume 2. If you enjoy it we hope you will consider purchasing the book, either print, eBook or audiobook. The Amazon link here will make the purchase easy.

Not having a reliable test for EPO, the UCI set 50 percent as the ceiling for a rider’s hematocrit. A finding of more than 50 percent was not to be considered a doping positive, because at the time there was no reliable way to detect synthetic EPO and therefore it couldn’t be proven to be the cause of a high hematocrit. A rider found to be over the 50 percent threshold was declared unhealthy and immediately suspended for 15 days, which would, the line went, allow him to become well enough to resume racing. The ruling had a perverse effect. Any rider hoping to be competitive had to dope himself up to the 50 percent threshold. Conconi takes credit for suggesting this rule to the UCI, but he had actually advanced a 54 percent hematocrit as an appropriate upper level.

Fifty percent was settled on because it was thought riders would be less likely to die in their sleep. Looking back at this, it all seems crazy. At the Tour of Romandie, Chiappucci was snared by the limit when he was found with a 50.8 percent hematocrit. The two-week suspension kept him out of the Giro.

Pantani’s spring program didn’t shrink from hard racing and even took him to the brutal northern European Classics, where he did well enough, including a fifth in the Flèche Wallonne and good placings in other races. Pulling out of the Tour of Romandie, he complained that his form was still lagging and that he would never again be the rider he had been two years before. He said he had tried to race too much too soon after his accident and was circumspect about his own prospects.

The 1997 Giro looked like a climber’s race. There were two time trials totaling 58 kilometers, the first one in stage three having a hard ascent at the end. Four stages with hilltop finishes, including a devastatingly difficult penultimate stage in the mountains, made it certain that a rouleur would not be triumphant in Milan. No prologue time trial was scheduled; the first stage would be sixteen laps up and down Venice’s Lido beach.

Because the Giro organization had botched the sale of the television rights by demanding insanely high prices, large areas of Europe either didn’t get the 1997 Giro at all or had to pay for it. Also, many riders with Tour ambitions decided to avoid tiring themselves in such a hard race. The result was a rather attenuated field with none of the world’s top-ten rated riders planning to contest la corsa rosa. There was talk that the status of the Giro had fallen even below that of the Tour of Switzerland.

Even so, the race still had plenty of good riders. Tonkov had won the Tour of Romandie. Enrico Zaina, who earlier had been Chiappucci’s gregario, was now free to race on his own account since Chiappucci was suspended. Frenchman Luc Leblanc was in good shape, having won the Giro del Trentino. The consensus was that if Pantani had returned to good form, the race would be between him and Tonkov.

Mario Cipollini won the first two stages. His leadout train lost control of the race in the final kilometers of the first stage, yet Cipollini bored through a nearly nonexistent hole next to the barriers and emerged the winner of the first Pink Jersey. The next day he led the sprint out from far back and no one could come around him.

Mario Cipollini wins stage two in Cervia

Cipollini’s days in pink had to come to an end, and with the uphill time trial in San Marino, they ended immediately: the course’s eleven-percent gradient spelled certain doom for pure sprinters. Tonkov won the stage with Evgeni Berzin second, 21 seconds slower. Tonkov thought Berzin would have turned in a better time if he hadn’t been over-geared in the first half of the course. Pantani did well enough, losing 1 minute 23 seconds. Tonkov was now the leader and Berzin was second, a single second behind.

So far the Giro had enjoyed lovely weather. In stage five, when the race arrived in Abruzzo with its hilltop finish at Terminillo, the rain came. The pack was all together for the start of the fifteen-kilometer, eight-percent grade and Tonkov had his team keep the pace warm during the first kilometers of the ascent. But soon Pantani’s Mercatone Uno men decided the speed had to be increased and increase it they did. That effort had two surprising victims, Berzin (who got the hunger knock) and Ugrumov.

With about three kilometers to go the sun came out. Several riders attempted getaways, but Tonkov easily rode up to each attacking rider, including Pantani. His neutralizing efforts looked almost effortless, usually without his even getting out of the saddle.

After a final attack from Leblanc, Tonkov took the stage and further padded his lead. The General Classification stood thus:

1. Pavel Tonkov

2. Luc Leblanc @ 41 seconds

3. Ivan Gotti @ 1 minute 7 seconds

4. Roberto Petito @ same time

5. Marco Pantani @ 1 minute 31 seconds

Going southwest without any appreciable change to the standings, the Giro arrived on the Amalfi Road on the southern Italian coast. It was a piano day and while the peloton cruised down the Tyrrhenian coast, a group of non-contenders was allowed their day in the sun and finished fourteen minutes ahead of the disinterested pack. But the day profoundly affected the Giro’s outcome in another way; thirty kilometers before the finish Pantani hit a cat while descending the Valico di Chiunzi. He didn’t break any bones, but after getting badly bruised and losing twelve minutes, he abandoned.

After going all the way to the heel of Italy, the peloton spent its rest day transferring up to the Tuscan coast. The order of business when the Giro resumed was to boot four riders from the race, none of whom were in contention for the Overall, for excessive hematocrits.

Stage fourteen took the riders almost due north, sliding by the east side of Turin on the way to the Alps. It ended with a 2,100-meter-high sort-of mountaintop finish at Cervinia, on the Italian side of the Matterhorn. After they reached the summit, they had a two-kilometer downhill rush to the line.

On the penultimate climb, the San Pantaleon, things broke wide open. A small group of riders including Axel Merckx (Eddy Merckx’s son) had been off the front for a while. Out of nowhere Ivan Gotti exploded from what was left of the peloton. Stefano Garzelli of Mercatone Uno was the only rider to mark the move. Gotti bridged up to the Merckx group with astonishing ease while Tonkov did nothing, keeping his attention on his bête noire, Leblanc.

Still Tonkov did nothing and Leblanc, not wanting to hand the Giro over to Gotti through inaction, led the chase. The Gotti group went over the Pantaleon 23 seconds ahead of the maglia rosa.

The Gotti group flew down the Pantaleon like madmen and by they time they got themselves organized on the way to Cervinia, they had enlarged their advantage to 64 seconds. Gotti, knowing the stakes involved, singlehandedly dragged his group up the hill.

With six kilometers to go the race had turned into an exciting pursuit. Up front Gotti was pounding away for all he was worth with Nicola Miceli hanging onto his wheel. One hundred seconds back, feeling the Giro slipping from his grasp, Tonkov had only Leonardo Piepoli for company while Leblanc, unable to maintain the white-hot pace, was nowhere to be seen. Tonkov had gambled and lost. Leblanc was not Tonkov’s main challenger, it was Gotti.

Out of the saddle and digging deep, Gotti dropped Miceli and finished alone. Tonkov lost 1 minute 46 seconds. Leblanc had cracked badly, coming in 3 minutes 16 seconds after Gotti, who had profited hugely from Tonkov’s tactical blunder. The new General Classification was thus:

1. Ivan Gotti

2. Pavel Tonkov @ 51 seconds

3. Luc Leblanc @ 3 minutes 2 seconds

4. Leonardo Piepoli @ 3 minutes 28 seconds

Gotti’s lead shouldn’t have been a surprise. He had been second in the 1990 Girobio, fifth in the 1995 Tour (including two days in yellow) and fifth in the 1996 Giro. Yet he had not been invited to the Giro presentation with the other contenders, a fact that was clearly on his mind when he spoke to the press after the stage, feeling he had been unjustly forgotten. They certainly knew about him now.

The Giro turned east for its appointment with what were intended to be the deciding stages: a 40-kilometer time trial followed by three days in the Dolomites.

Normally, since Tonkov was the superior time trialist, Gotti’s lead might have been in danger. But just before the stage start the judges wouldn’t let Tonkov ride his time trial bike because it had a projection over the rear wheel the officials deemed an illegal fairing. Tonkov switched to his back-up bike, one he didn’t really like. The result? Tonkov was able to take back only fourteen seconds. The bike switch might actually have been a blessing because the hard-to-handle specialty time trial bikes proved to be lots of trouble on the technical, high-speed course. Both Alexandr Shefer (now lying in fourth place) and Leblanc were among those who crashed hard. Both riders abandoned.

Ivan Gotti in pink with Pavel Tonkov

At 5:30 in the morning, before the start of stage nineteen, NAS raided the hotel rooms of the MG-Technogym riders and found a large cache of dope. Among the finds were twenty boxes of anabolic steroids, three boxes of growth hormones and of course, EPO. At first team director Ferretti said the drugs were for his personal use, to help him improve his sexual performance. As we say out here in the Ozarks, that dog don’t hunt. It was later admitted that the drugs were for the riders’ use. The team left town that afternoon and the sponsors quit the sport at the end of the year.

Rain and six major climbs greeted the riders at the start of stage nineteen. Just listing what the peloton had to get over during its 222-kilometer Calvary is tiring: the Pinei, Sella, Pordoi, Campolongo, Furcia and the Riomolino with a final uphill grind to Falzes.

Tonkov, who crashed and remounted on the Campolongo, could not contain Gotti. On the Riomolino, Gotti, who had Leblanc teammate Giuseppe Guerini for company, had been hoping he would be able to work with and help Leblanc as a foil to Tonkov. With Leblanc now out, Guerini was given the go-ahead to work with Gotti and try to improve his own standing, then sixth place. Gotti was able to extend his lead by another 55 seconds.

The new General Classification shows it was a two-man race:

1. Ivan Gotti

2. Pavel Tonkov @ 1 minute 32 seconds

3. Giuseppe Guerini @ 6 minutes 0 seconds

4. Nicola Miceli @ 8 minutes 33 seconds

The stage nineteen seven-hour ordeal must have been enough. Even with stage twenty’s finish at the top of the Tonale, Tonkov made a few half-half hearted attacks which Gotti, content to merely stay with Tonkov, easily handled. A group of non-contenders was allowed to come in ten minutes ahead of the maglia rosa. Now it was down to just one last mountain stage, with three hard passes, including the Mortirolo.

Tired or not, Tonkov’s Mapei team wasn’t going down without a fight. They sent Gianni Bugno up ahead and then set a pace so hot that eventually nearly everyone was dropped. It was down to just Gotti and Tonkov as they caught Bugno on the Mortirolo.

The gradient rose to eighteen percent and on a switchback, a motorcycle fell over in front of Bugno. Now it was Gotti and Tonkov, the two best riders, riding side by side on the Mortirolo, one of the hardest ascents in cycling. Gotti tried several times to drop Tonkov, but the Russian stayed with him. It was thrilling duel. Finally Gotti took the front and it looked like Tonkov had thrown in the towel, but two kilometers from the summit there was a surprise. Wladimir Belli closed up to the two leaders and then led for the rest of the climb through a sea of fans lining the narrow road. The tifosi were sure an Italian was going to win the Giro and they weren’t going to miss it.

Tonkov won the three-up sprint, but with only the final ride into Milan remaining, the Giro was Gotti’s.

Ivan Gotti wins the 1997 Giro d'Italia

Final 1997 Giro d’Italia General Classification:

1. Ivan Gotti (Saeco): 102 hours 53 minutes 58 seconds

2. Pavel Tonkov (Mapei-GB) @ 1 minute 27 seconds

3. Giuseppe Guerini (Polti) @ 7 minutes 40 seconds

4. Nicola Miceli (Aki-Safi) @ 12 minutes 20 seconds

5. Serguei Gontchar (Aki-Safi) @ 12 minutes 44 seconds

Climbers’ Competition:

1. José Jaime González (Kelme-Costa Blanca): 99 points

2. Mariano Piccoli (Brescialat): 35

3. Roberto Conti (Mercatone Uno): 28

Points Competition:

1. Mario Cipollini (Saeco): 202 points

2. Dimitri Konyshev (Roslotto-ZG Mobili): 146

3. Glenn Magnusson (Amore & Vita): 145

.